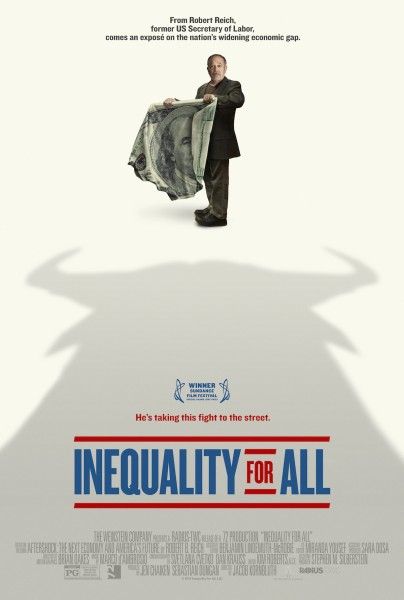

Robert Reich makes a compelling argument on behalf of the middle class in Jacob Kornbluth’s must-see documentary, Inequality for All. The film offers an intimate portrait of the UC Berkeley professor, best-selling author, and former Clinton cabinet member as he demonstrates through fascinating classroom lectures, interviews, news clips and graphics how the widening income gap has had a devastating impact on the American economy and our democracy. Reich uses humor, passion and a wide array of facts to connect the dots and explain why our economy is in crisis, how the issue of economic inequality affects all of us, and why it isn’t just about moral fairness.

At a recent roundtable interview, Reich and Kornbluth discussed the genesis of the project, how they set out to make a complex subject accessible so audiences could connect in a powerful way and better understand the issues at stake, how they used the clever image of a suspension bridge to illustrate the connection between the two greatest financial crashes of the past century, why you have to step out of the 24-hour news cycle and avoid the blame game to grasp the bigger picture and inspire positive social change, and their plans to collaborate in the future. Hit the jump to read the interview.

Question: This is so enlightening. You’re the teacher everybody should have had.

ROBERT REICH: Well the class is pretty big. You can still come back to Berkeley. I’ve got fifty people who are graduates who are just coming back.

JACOB KORNBLUTH: That’s how I felt in the class. I didn’t take it. I had never seen the class, but when we started making the movie, I thought, “Man, this is the class I wished I could’ve taken in college from the teacher I wished I could’ve taken it from.” So that’s when the classroom became part of the film. It wasn’t part of the movie in the initial conception. It was quite a discovery.

What was the genesis of this film? This problem has been going on for some time and we’ve seen the economic decline over the years.

REICH: And I have been writing about it and I have been trying to do something about it. I’ve been in Washington and I’ve been banging my head against the wall. One day Jake came into my office and wanted to do this film based on my most recent book. I was skeptical. Let’s put it gently.

KORNBLUTH: Well, it’s pretty close to that. I actually wanted to do the movie before I read the book, because we had known each other a bit and I was interested in knowing what the story about the economy was for myself.

REICH: That’s right. We’d done some two-minute videos.

KORNBLUTH: I had in my mind this sense as somebody without an economic background that I was a perfect first audience for this stuff, that if I could get it, then maybe everybody else could get it. I realized that in the bigger economy I had been trapped in the 24-hour news cycle. I kept hearing people discuss income inequality and what was happening to the economy after the crash in 2008, and I didn’t understand what was going on. I didn’t get it. And I was frustrated with that. I understood that the Democrats thought this and the Republicans thought that, but I didn’t understand what had happened. I didn’t have any context for it. So I was hoping to do some sort of story that put all of this in context. And then, his book was paradigm shifting for me. I hadn’t thought about it in that way. I didn’t realize that this widening income inequality was affecting our economy and our democracy. I had understood it maybe in moral terms coming into it. I had understood that maybe it just wasn’t fair that people had this amount and everybody else had that little. But now I had a new framework to understand it, and that it was bad for our economy overall, and it was bad for our democracy also.

Was this the Beyond Outrage book?

REICH: No. This was Aftershock (Aftershock: The Next Economy and America’s Future). Beyond Outrage was really a collection of essays, so the last large book was Aftershock. I did try to summarize what I thought had happened to the economy over the past thirty years, and how widening inequality had a role to play in the financial crisis, and we would still be struggling to get out of the gravitational pull of the great recession because of it. Jake did something that I didn’t think was possible, and that was put it into terms in movie language and art form that at least the audiences we’ve had at screenings have found incredibly powerful.

It’s also the way you use the suspension bridge to analyze what’s transpired in the economy over the decades. It helps us visualize what you’re talking about.

REICH: That was Jake’s idea.

KORNBLUTH: Well, that was maybe the “ah ha” moment that made the movie come together. At the beginning of his book is this graph, and it has 1928 and 2007, and it looked to me so clearly like a suspension bridge. I was like, “My goodness gracious, is it really that clear? That just before the two biggest crashes of this century the most concentrated income was in the hands of the one percent.” And when I saw that, I thought I had to know more. I knew that there was enough in there that was intriguing to me that I wanted to understand it more. But it was the initial visual “ah ha” that made the movie make sense to me.

What made this the right time to make this film?

KORNBLUTH: It’s interesting. I don’t know. It would be an interesting thought experiment to see what would happen if you made it a few years earlier so that it came out around 2008, say for instance. I woke up to this around 2008 when the economy crashed. What I realized was a lot of people of my generation were pretty cynical about politics. We didn’t feel like we could participate and I had never really participated. I had just reached my personal limit, like I had to get this and I felt like I had to do something about it. In that way, I’ll bet there are other people like me. I bet there are people who to this point have not been invested in economics and politics. I’m hoping when they see the film that they turn around. In a certain way, this film is not just of this moment. I feel like it’s not pinned to one news cycle. I feel like it will be useful for people to see next year, and it would have been interesting for them to see it last year. It’s one of those stories that’s maybe a little bit bigger and a little bit less pinned to one time. I could see it useful in a bunch of different eras.

REICH: Well, it’s also very important for people as we come out of the financial crisis of 2008 and 2009. It’s dawning on people that there’s something fundamentally wrong with the economy. They’re working harder than ever and they’re not getting ahead. We’re supposed to be in a recovery. This is not a recovery for me. I can see there are a very few people at the top who are running off with most of the gains. If this movie had come out during the financial crisis, everybody would be focused on Wall Street and the financial crisis. Now is the perfect time as we come out of the recession when the realization is dawning on people that there is something more fundamental going on that we can actually teach.

KORNBLUTH: That’s exactly what happened to me, what he just described. I had this realization that maybe this isn’t right. Maybe there’s something wrong here. I felt like the partisan terms I was getting the message through weren’t teaching me anything. I wasn’t learning anything about it. Just because the Democrats feel this and the Republicans feel that wasn’t really educating me on it.

That’s one of the interesting aspects that I found with the film is how everything is connected. You’re not blaming Wall Street. You’re not blaming politicians. It isn’t just one thing.

REICH: It’s not a blame game. One of the things I tell my students is that if you want to understand what's been going on and also what needs to be done, you’ve got to get out of the blame game. Some people on the left want to blame the rich and corporations. Some people on the right want to blame the poor and government. Either of those frames of reference gets you nowhere and they aren’t even truthful. You’ve got to understand the dynamic itself and how we got into this position. Why is it that globalization and technological change have not had nearly the same effects of pulling societies apart and creating massive inequality and economic insecurity elsewhere? It’s a failure of understanding that we can change the rules of the game and have a much more prosperous society overall. It’s not a zero sum game in which the only way the middle class and the poor gain is if the rich lose. I mean, the rich would be better off with a smaller share of a rapidly growing economy and a less vitriolic society than they are now.

KORNBLUTH: I would say what you just said about the dots connecting. How the dots connect in this film is where my framework got rocked or where I felt like it was a paradigm shifting idea for me. It wasn’t just one thing. It wasn't just, “Boy, campaign finance reform needs to happen,” although it does. And it wasn’t just, “Wall Street reform needs to happen,” although it does. It was that they’re all connected. For me, I have a feeling on a personal level that my community and society isn’t as cohesive as I want it to be. I’m not as connected to my fellow citizens in a way. I’m a little bit too cynical about politics in general. I started to see that all of these things are connected, that maybe to me the biggest story of our times is this widening income inequality, this growing income inequality, because it affects every aspect of my life on a daily basis in a way that I feel. I’m worried economically about the future. I’m worried that my parents’ generation had a little bit easier run of it than I’m having or me and my friends are having. I’m worried about politics being just so partisan. I feel beaten down by it. But what if all of those things are connected? The big story here is that the structure of the economy is organized in such a way that makes it so that it’s not for the good of our society. It’s not the best America that we can build. I’m hoping that when people see this film, they change this from a moral question of widening income inequality and isn’t it just too bad to something like if we want to have an America that works for everybody and that’s good for us and all of our citizen that we need to fix this. It’s imperative that we do something about it and that we not get beaten down over it.

What was the moment where you overcame your cynicism? I’m in that same boat but with just a little bit different oar. And what do you tell your students who come away from the class asking what they can do to change things even in a small way?

REICH: Well, cynicism is the largest obstacle to social change and part of the course, and even part of the movie, is historical. I mean, you’ve got to understand that the United States economy has been here before. We’ve continued to save capitalism from its own excesses again and again. We did it in the Progressive era between 1901 and 1916. We did it in the Great Depression and the New Deal of the 1930’s. We expanded equal opportunity in the 1960’s. It’s a never ending challenge. The problem is that over the last 35 years we as a country have not been as vigilant as we need to be. So, it’s possible. We know it’s possible. Cynicism is dangerous because people throw up their hands and say, “Well it’s not possible. Why should I even try?” That’s the end of the road.

KORNBLUTH: One of the interesting points that comes up around this topic is generational. Bob always says when we talk about this that when he was growing up, he had examples of social change happening and playing out in front of his face. It was taken as sort of a given. It was Robert Kennedy, the Civil Rights Movement, the fight against the Vietnam War. He lived through a bunch of things, and he saw change happen when his generation put their foot to the floor. For me, I never saw that. I grew up in an entire period of feeling as though we weren’t affecting change at all and that we were losing our democracy or that we didn’t feel in control of it. That was certainly the experience of me and my friends. But we’ve talked about this. After making this movie, I feel more optimistic now than I did before making the film. So, one of the things is make a film about income inequality and you’ll feel better about it. But the other thing is that there are these tipping points. There are these things when you feel as though you can’t see your way out of something. But as he said, if you look at it historically, whenever we get to those points when it feels like you can’t do anything about it, everybody rallies around and something happens. There’s a tipping point, and then it changes, and it feels like it happens sometimes overnight, although I don’t like anybody to think about this happening quickly. I like to think about it as a long fight, but we could find its tipping point soon. We’re at an extreme right now. If we step out of the moment in our partisan fights, we see that this economy and this democracy are dysfunctional because of how unequal this society has become, and we have to do something about it.

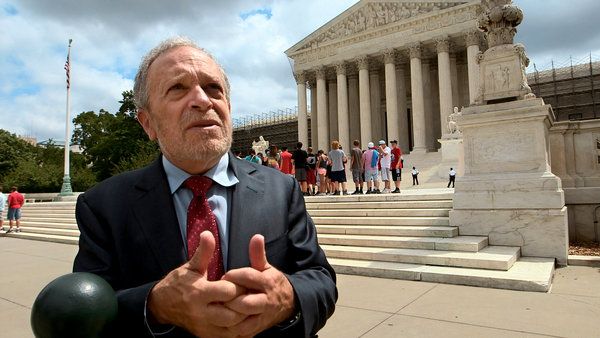

Bob, recently in an interview with Bill Moyer, you referred to yourself as a vehicle to open people’s eyes and minds with this film and to educate them on some of these issues. How do you see yourself in this scenario here?

KORNBLUTH: I guess if he’s the vehicle, then what is that?

REICH: You’re the car mechanic.

KORNBLUTH: That actually is much more personal and hands on than I was thinking of as a metaphor. Look, there are two ways to answer the question. One of them is, we discussed going in that we both knew we wanted to make a film about widening income inequality. But that’s the message, and I felt like you needed to get to know the messenger to hear the message. And so, against his will to a certain extent, we had to open up his personal story as part of the film.

REICH: This was a point of, I wouldn’t say tension, but there was some difference of opinion, because even though I’ve been in government and I’ve been out there on the front line, I’ve kept my personal life fairly private and [certain] aspects very private. But Jake convinced me that it was important to use my biography as a vehicle, again that word “vehicle,” for enabling people to connect with this subject.

KORNBLUTH: As far as the making of the film itself, I mean, it is true that maybe he didn’t know what he was getting into when he signed up for the film, but that allowed me a fair amount of time to just study for myself and to try and understand what he was saying, which was the only way I could make a movie about it. It wasn’t clear to me what the history of taxes was and what effect taxes have on a society. That was a tremendous amount of work to understand each and every aspect of economics. I was shocked when I would pick up these books just how complex these topics were to wrap my head around. And then, I’d go back and read his book and sort of measure my understanding, because I’d try to have my own ideas and then measure them against what he had come up with. You’d see him boil it down and in a deep way thoughtfully put it together, and it raised my admiration for his argument. But I had to, in some ways, come to peace with the argument for myself. I couldn’t just make a movie if it was his argument and put it together. I had to understand it myself. So, I had to understand the story I wanted to tell, understand his story, and then see how the two things lined up together to make the movie. In terms of vehicle and being a driver, I think they were parallel journeys, like the 40 years of him talking about this issue and his work and also my personal journey in understanding what the movie is that I wanted to make for myself.

When your film screened at the Los Angeles Film Festival this summer, you mentioned you had ideas for future projects you planned to collaborate on. How will the two of you work together in the future to build on what you’ve started here?

REICH: Well, I’m certainly going to find out from Jake better than I did the first time how much work is entailed. (laughs) We have become very good friends over the last couple of years working on this project and some other projects, and there’s a great deal of trust. I trust Jake’s artistic judgment and his extraordinary abilities as a filmmaker. We’ve talked about a television show. We’ve talked about a variety of things, but I hope this is just the beginning.

KORNBLUTH: I can tell you, going into a project like this, sometimes when you meet a public figure who you admire and you get to know them, you’re in danger of tearing down some of what the ideal was that you held about this person. The more I’ve gotten to know him over the making of this film, my admiration has just grown. I mean, it’s amazing that he’s fought this long and this hard for something that he believes in. It’s an inspiration to me. It’s amazing to have somebody thinking about this problem in a way that feels in some ways less piecemeal and in some way that I can wrap my head around. He has an absolute gift for breaking down complex issues in ways that somebody like me or anybody can understand, and that’s been a real gift. So, I know that that’s there. And, like you said, the trust and the friendship is there. We’re just going to keep finding stuff to do. I mean, we have to. I don’t know which exact, specific project it’s going to be, but I can tell you that we’ll keep working together.