From a visual standpoint, there’s a very fine line to ride when making a character drama. You want the image to be striking and appealing, but you don’t want to detract from the performances or dialogue too much. Cinematographer Sam Levy has a knack for walking this line to terrific results, having broken out in a big way with shooting Kelly Reichardt’s 2008 film Wendy and Lucy and most recently working some serious magic on Noah Baumbach’s visually dynamic Frances Ha, While We’re Young, and Mistress America.

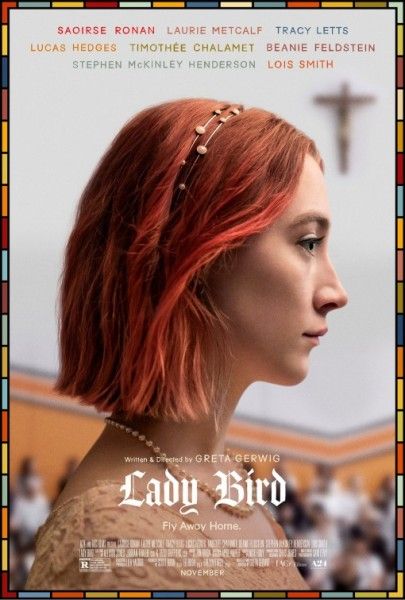

And now Levy has lent his talents to a highly anticipated directorial effort from actress and screenwriter Greta Gerwig, serving as the director of photography on Gerwig’s delightful, surprisingly emotional coming-of-age story Lady Bird. The story takes place in 2002 and stars Saoirse Ronan as an outgoing high school senior who navigates friendships, romantic entanglements, family, and impending college decisions with a mix of confidence, naiveté, and anxiety.

With Lady Bird opening in select theaters on November 3rd, I recently got the chance to speak with Levy about his work on the film. He discussed his close bond with Gerwig, their extensive planning, what she’s like as a director, and how they developed an aesthetic approach that would feel like a memory. We also discussed Levy’s relationship with his mentor Harris Savides, as the DP shared a nice story that partially encapsulates what he learned from the cinematography legend. And Levy teased a couple of collaborations with Spike Jonze on a pair of upcoming projects.

Levy offers a lot of insight into how one approaches shooting a film like Lady Bird and what a close relationship with the director like Gerwig can bring. Check out the full interview below and definitely check out Lady Bird when it comes to a theater near you.

I know that you worked with Greta on a couple of Noah Baumbach's films but I was curious, how did you first come to be involved in this?

SAM LEVY: Greta and I did three movies together. Frances Ha and Mistress America with Noah Baumbach and Maggie's Plan with Rebecca Miller. We've worked together a lot and knew each other for many years before she offered me Lady Bird. She actually first mentioned it to me at a premiere party for Mistress America and she was extremely humble in the way that she brought it up. She said, "I wrote this thing that I'd like to direct and I'd love to show it to you but if you don't want to look at it, it's totally fine. If you do look at it and you don't want to shoot it, that's totally fine." I was like, "Oh, just can I please read it?" I knew she was working on something. It's like, "First of all thank you for thinking of me because I know it's going to be amazing and yeah, I'd love to read it." I read it. It's such an amazing screenplay and that was it. It was probably a couple days after that we met at the Noho Star restaurant in the East Village and just started talking about it.

That was another one of my questions was what were your early conversations like in terms of the visual approach to this film? What were some of those early ideas?

LEVY: One of the first things Greta said to me was that she wanted the movie to look like a memory, which immediately got my attention and made me excited. When she said that I knew exactly what she meant, but despite knowing what she meant, the thing was, how do we do that? How do we create something that looks like memory? Something that's dynamic that isn't just using commonplace methodology that everyone uses nowadays in motion pictures like making things sepia or just crude black and white or diffusion. It's not about that. It's more of an organic and internal sensibility. We talked about it some more. I said, "I know what you mean but let's keep talking about it." She said, "Yeah, at a visceral level it should feel like the movie is over there." She extended her arm and held up her palm as if to say, you're connected to the movie but my palm, which is the screen, is slightly removed from the viewer, but not overly so. We talked about it some more and then together, both of us equally came up with ... I think she said, "It almost should be plain. It should almost look plain," and I said, "But luscious." She said, "Yeah, plain and luscious." We started saying that a lot. Plain and luscious. Plain and luscious. It should be beautiful but not distractingly graphic, so that you can engage but have a nice aesthetic bed to fall into and luxuriate in but not distract from the story or the performances or the words.

Did you guys shoot this on film or digital?

LEVY: We shot it with an Alexa. Digital.

That's surprising, honestly. Because it has that feel that you're talking about where it's somewhat—I feel like sometimes with digital it's too lifelike, too realistic, and you don't have that sheen of watching a movie.

LEVY: I think Greta's first thought was it shouldn't be too real. It should be a little removed. It should feel like a memory. The way that a memory looks when you envision it. From there after we had these great allegorical conversations where we started to get at the technique of memory and cinematography. A photographer that we were looking at a lot was Lise Sarfati, who's this brilliant French photographer. She's done a lot of amazing work. She's done these amazing portraits of young women about the age of Saoirse's character and they're very sensitive and soulful. We were just looking at different photos from the era. A lot of high school yearbooks. It's a high school movie. High school yearbooks from the early 2000s and we started to notice, especially in high school yearbooks, photos have this quality of—they look crappy and distressed. It's like a color Xerox or it's taken with a point-and-shoot 35mm camera. By the time they make it into the yearbook, it's like several generations have been removed from the initial image.

We happened on this technique in the production office. I took a photography book we were looking at and I made some color copies of some different photos because I wanted to tack them up on the wall so Greta and I could look at them and be inspired. Just have things to look at while we were shot-listing and digesting all the location photos we were taking. I started to notice when making these photocopies, it distressed the image much like the yearbook photos, and sometimes you could take the photocopy and re-copy it and it'd lose another generation and you could lose another generation still and distress it to the point that it really looked like these yearbook photos but it was a technique we could utilize in our own way, in this professional context but still bearing in mind the youth who create their yearbooks.

That really cinched that it was this aesthetic of memory that we'd been talking about and then it got us talking about a lot of different things. The early 2000s was a time when high school kids, college kids, would go to Kinko's and make copies of different things. Term papers or photos to decorate their rooms or their apartments or their dorms. It just seemed to evoke the era in all these different ways. Then we used these distressed images as a reference for how to photograph the movie using the Alexa. Meaning that the color photocopier has its own sensor that scans the image just like the Alexa has a sensor that captures the images in front of the lens. How can we emulate these multiple photocopied images using the Alexa? The quest then came to be, playing digitally which is totally appropriate but how can we create something within this aesthetic of memory that is unique and of its own and not just taking scans of film grain and overlaying them, calling it a day? Which is very commonplace now.

I think it works. I'm 30 so I came of age around the same time and something that really struck me about the film is that it feels of that time but it's not dripping with nostalgia. I couldn't quite put my finger on it but it feels like you pulled off a magic trick where it felt like I was transported there without feeling like the frame was loaded with "remember this" references or like you said, covered in sepia tone or something like that. I think that the memory aspect that you guys did, I think you really pulled it off.

LEVY: Oh, thanks. I'm glad you responded that way.

Were there any other discussions about that specific technique of transporting the viewer to that world without dripping in nostalgia?

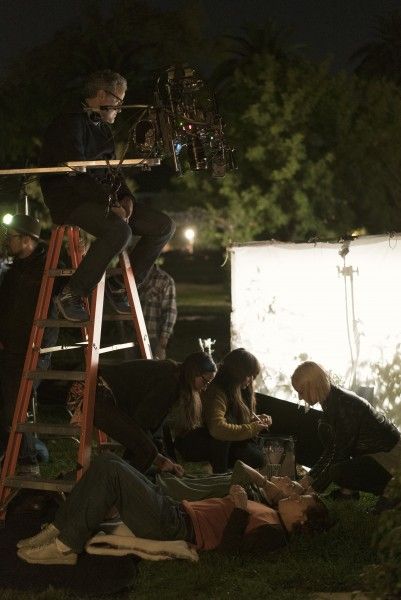

LEVY: There was a lot of discussion about it. Much of it was grounded in the shot-listing process. Greta and I had the benefit of a lot of lead time and we also both live in New York and we liked hanging out with each other so we would get together on weekends or whenever we were both off and we could find a few hours here and there, and we just started going through the movie. I would sit at my computer and I would read the script to her so she could hear her dialogue and then we would just mark down, "This one, we can try and do this all on a wide. We'll move around, we'll follow Lady Bird. This scene, she's in the car with her mom, we'll probably want some additional close-ups." We'd try to anticipate editorially where she would want to cut in and out and especially the transitions from scene to scene. We shot-listed the movie twice. We managed to get a pass done before the official prep for the movie started and when the official prep started we went through it again and this time I added all kinds of photos and stuff to each scene. I'd always diagram the blocking. I had a piece of graph paper and I would diagram, "Lady Bird's going to be here by the door and then she's going to move to the kitchen, then she's going to move back to the door and Laurie Metcalf is going to stand still. Tracy's going to be following," and so on. Where appropriate I put maybe a reference photo of Lise Sarfati or the Sacramento painter Wayne Thiebaud.

Then during prep what I started doing a lot of was I had location photos, especially once we'd locked locations. I'd put them in. When it was all said and done the shot list was 110 pages, which is about the length of the script. Greta and I pretty much had that thing memorized by the first morning of our first shoot day. We had a brilliant First AD Jonas Spaccarotelli. The three of us really had that thing down and we distributed it to everybody, to everyone on my team, everyone on the AD team, production design, costumes, sound, everybody. Everybody had a sense of "Here's what we're going to try and do." Of course we'd shift and change some things, as happens, but never drastically. Greta and I would know right away if we'd look at a blocking, maybe one of the actors had an idea or we'd just glance at each other and we'd know we need to do less. Usually it was we need to do less than what we'd anticipated.

To answer your question, the planning of the character blocking, the camera blocking, really informed creating the aesthetic of memory. Even though you don't sit there and be like, "When she's walking through the parking lot how can we make that like a memory?" Not really about that. It's just designing everything to be as dynamic and lively as possible with the best possible transitions. Then with that we used the technique of distressing the image just up to the point where—when we were doing tests and especially when we were timing the movie, we'd push things in lighting the movie, photographing the movie, push things up to a point where it was like, "That's too much. Now it's too luscious. It needs to be more plain." We'd always know the moment something was too luscious or would override the story or what people were saying. Really it's that the design of the image needed to fit alongside the tempo of the work. The musicality of the dialogue and the music itself, the score by John Bryant. The editing by Nick Houy and then Chris Jones's design, April's costumes.

What really struck me about the film was that there's this confidence and this assuredness behind the camera without the pretension or pomposity, which was refreshing given that Greta isn’t some veteran director. It feels like she's been doing this for years and the way she handles the characters is just brilliant. What was your working relationship like on the set with her as a director?

LEVY: It was amazing. As good as it gets. It was absolutely what you dream about. As I mentioned we had this exhaustive amount of prep. Everybody really put in a lot of work making a blueprint and designing things to be just how we wanted them and then when we got to the shoot, of course everyone has butterflies before the first couple of days. You just really have to stay on the ball, stay focused, make sure everything's fitting together with the schedule. There's a lot of pressure. We want to create something transcendent and in order to do so we have to be very responsible to the schedule, to our budget, to our producing team who are amazing, very supportive, and positive. Greta was just so in her element on set. Working with the actors, working with us. Being a great collaborator, giving us room. She played music. She had all these great playlists that she'd made. A lot of songs from the era, from the early 2000s, all kinds of different songs. She knew exactly when to play music. When we were setting something up and the actors were maybe off preparing their lines or something. It just really created a great atmosphere. Then just about at the time we were wrapping up she'd slowly fade it out and then we'd get to work and start shooting.

That was indicative of the attitude towards the whole. She was just highly focused, highly efficient but not prone to pulling all-nighters and working recklessly hard. She's just very engaged. It's inspiring. She was constantly inspiring all of us. Then she has wonderful taste. She loves great films, great music, she's a voracious reader. In that way she's inspiring to all of us also. All of us, we'd do anything for her. She just got us to a point where you want to move heaven and earth for that kind of person.

That's so great to hear and I definitely see much more from her to come as a filmmaker, because again as I said it feels like she's been doing this for years.

LEVY: It does. The fact is, she has. She hasn't actually directed a movie on her own but she's worked with amazing people, actors. Written, co-directed. She's done so many things on great movies with great cinema personalities. She certainly absorbed a lot of that but the fact is she's her own cinematic being. I knew that the moment she said, "I've got this thing, would you read it?" It's like, "This is going to be amazing."

I also wanted to ask you, I know you first started out as an apprentice to the great Harris Savides. I was curious, what did you learn from him as you were honing your craft?

LEVY: I feel like I learned ... I'm overwhelmed. It's an overwhelming thing to answer. I miss him a lot. He passed away about five years ago now. I learned an incredible amount from Harris. Maybe I'll give you an anecdote that can answer that question. It's from a different film I worked on called Wendy and Lucy. I worked for Harris a lot as an AC. I did a lot of commercials and then I worked on a movie called The Yards that James Gray directed as his Photoshop Tech and I took all of his lighting diagrams. A liaison to the lab for him. I oversaw the consistency of the dailies for him and James Gray, which was an amazing job to have. Then not long after The Yards I started shooting on my own and I did a few movies that no one really saw and then I got Wendy and Lucy, which was my third movie. It was for the great Kelly Reichardt and we shot Super 16 and I really started to put a lot of my training from Harris into play.

I was just at a point where I was really trying to do my own thing but I was still talking to Harris a lot and I called him just to check in. I was testing all kinds of stuff and I what I was finding when I was testing was that the less I did, the more I liked the image. I tried all kinds of extreme exposure and force processing and all these technical tricks that I'd learned under Harris, that I'd seen him utilize very thoughtfully and Harris is just an amazing alchemist who could utilize obscure lenses. Different kinds of chemicals in the bath. Printing things using new film stock or even using like sound stock that had some kind of an emulsion that he discovered you could print on. He was just a wizard. I was finding the more of these techniques I did the less I liked it and the less I did the more I liked it.

I called him. He was photographing Margot at the Wedding for Noah Baumbach. I ran all this by him. I said, "I don't know, I'm doing all this stuff but when I do very little that's when it's the best," and he said, "What's the problem?" I said, "I don't know, I just wonder if I should be doing more." He said, "Let me tell you about what I'm doing. We're shooting Margot. We're using these Super Baltar lenses. I'm flashing all the film. I'm underexposing everything almost three stops. I have to stay up all night watching the films, checking the consistency and my life is not simple." I said, "That sounds amazing. I can't wait to see that." He's like, "No, what you're doing sounds amazing. I can't wait to see that!" I just learned an incredible amount from Harris.

What I learned, maybe it's in that anecdote somewhere is that there's a lot of technical things that go into cinematography, but it's not about that at the same time. You have to have mastery over your craft but in such a way that the technique doesn't overpower the whole. If that makes sense. Also, I was fortunate to grow up in a musical household. My father was a concert violinist with the Boston Symphony. What seemed very familiar about what Harris would tell me about less is more, be aware of what more is but less is more. My father would say— I played cello growing up and I'd hold the bow. My father would smack my hand and be like, "Lighter, lighter. You should barely be holding onto that bow. Nice, delicate approach when you're playing." Cinematography is the same. You can't hold on to technique too hard. You have to be aware. Gordon Willis used to say, "I just want a camera that works. I want a camera that works, I want lenses that work." In so many ways we strive for greatness but at the end of the day so much of it is making sure that the image is in focus. That you have a decent composition. You have the people in the frame and they're sharp. Sometimes it comes down to just that. No matter what anyone says when they talk to you.

That's definitely true. That's a really nice story. I don't want to take up too much of your time but as a huge Spike Jonze fan, I have to ask if there's anything you can say or tease about your two projects with him? Changers and the Frank Ocean thing.

LEVY: The Changers thing, you'll actually see something we did for The Tonight Show. The Changers piece was a dance piece that Spike wrote and directed as part of opening ceremonies Fashion Week show in New York this year. He wrote this brilliant dance piece that Ryan Heffington choreographed and we ended up shooting a film around the piece and then the only thing that I can really talk about is this thing that actually was broadcast on The Tonight Show which was a live one-take film with one number from the show. We did that and I spent the summer working for Spike on Frank Ocean's summer tour, which was a tour of different music festivals in Europe and then the U.S. Spike and Frank are working on something with all that footage but at the time, Spike and I were on-stage shooting with all of these different cameras and the images were part of Frank's live video show. We had someone mixing all of these images from my camera, Spike's camera. There was a whole camera choreography where we'd have the set list and then each song Spike would grab a mini DVD camera. I'd grab the Alexa with an anamorphic lens and then the song would change and I'd grab an infrared camera and Spike would grab an Alexa, and so on. I have all of these great set lists from different shows where we'd map out this camera choreography.

Frank, being Frank, sometimes he'd switch up the set list or he'd repeat a song so we'd have to adapt on the fly and it was really exhilarating. It was great. Spike's just the loveliest person and just full of energy and he's an amazing camera operator. I think probably coming from skateboarding and all his incredible skate videos, he's one of the best handheld operators I've ever seen. He can run backwards, which is a notoriously difficult thing to do handheld. Even just walking backwards, it's usually very bumpy. He's like a human Steadicam. I don't think he'd mind me saying that. It was just really great.

He, in his way, became part of Frank's show and Frank was into that. There was this one night of shows in New York. There was another camera that would come up out of the ground and my friend was operating it. We called it the Tower Cam. A big post would rise up out of the ground and then Frank would play to that camera at different points during the show. Before it had come out, out of the ground, Spike was leading Frank, walking backward, handheld and I was watching him. I was like, "Wow, he's four steps away from the hole where the Tower Cam is. Well, it's Spike. He knows it's there." Took two more steps and I was like, "Oh my god, he doesn't know it's there." I was about to throw my camera down but I was too late, but Frank Ocean just grabs him in front of 40,000 people. He kind of fell. Grabbed him, pulled him back out. They laughed about it and they just kept going. It's like, "Oh my god."

That's amazing.

LEVY: If he hadn't have grabbed him I don't know what would've happened. It was amazing. That came about, Spike had gotten my name from my agent. Got me in the mix for Spike's Frank Ocean project and then Spike called Greta, like, "Hey, is this guy okay?" He later told me, "She raved about you." She's always been great to me. If there's a one-day anecdote—it was the first or second day of shooting Frances Ha, which was a long, involved process. We were a very small group and I brought these big carpenter's kneepads with me because I had to be down on the ground a lot and the camera had to be low. We just didn't have any apple boxes, because we were so small. I was just like, "I'm bringing these kneepads." I had just felt like, "You know, I'm going to be on my knees all day tomorrow." We're setting up. I put these things over my pants. Nothing looks less cool than these huge carpenter's kneepads. They're big and plastic and just not cool. I get down on my knees and there's one of the other crew members that was making fun of me. Making jokes like, "Why are you bringing those knee pads?" Greta just stopped him in his tracks. She was like, "Hey. Stop it. He's just prepared. Leave him alone." It was just so great. I was totally ready to take the guy outside and be like, "Knock it off. I don't want to hear it anymore." I can fend for myself. It was just great. She rose to my defense and since then, it's like, "I really like her." I like that ... Even the way that she told this guy to back off, it wasn't cruel. It was just like, "Hey. This guy is just prepared. Leave him alone." That's Greta.