When you think of Samuel L. Jackson, what do you think of? When I think about him, my brain tends to go to where I remember first seeing him, namely as Stacks, the low-level criminal from GoodFellas who has one of those famous “misunderstandings” with Joe Pesci’s psychotic gangster. For most people, however, the first thought is of Jules Winnfield, the hitman with the carefully groomed Jheri curl who works alongside Vincent Vega for Marcellus Wallace in Pulp Fiction, and probably skip directly to his “great vengeance and furious anger” speech. There’s a good reason for that, and not just because Pulp Fiction is, well, Pulp Fiction, but because “great vengeance and furious anger” has always been what Jackson does so well. He rarely broods, preferring explosive, unrelenting torrents of roused disbelief and fury, belted out with urgency and end-of-the-rope exhaustion. The varied, near-musical timbre of his delivery teases out emotional undercurrents and humor in the dialogue that otherwise would have been diluted or simply absent from the film.

Jackson's early collaborations with Spike Lee, still one of the greatest American directors to be working fruitfully today, allowed the performer to hone his preternatural sense for conveying impassioned acrimony and desperation, especially in Jungle Fever and the oft-overlooked, excellent Mo’ Better Blues. His subsequent supporting turns in GoodFellas, Patriot Games, Jurassic Park, Menace II Society, and True Romance expanded his range exponentially, allowing him to build the scalpel-sharp comic timing that helped him to co-lead both Amos & Andrew and Loaded Weapon with such assured delivery and unbound physicality. Of course, it was Pulp Fiction that rightly solidified the actor’s relationship with Quentin Tarantino and opened the gates to more mainstream work and some far more challenging roles.

Since then, he’s been working consistently, even vigorously, and his potency has rarely declined, whether in goofy B-movie fare like Deep Blue Sea and Snakes on a Plane or providing the voice of Frozone in Brad Bird’s beloved The Incredibles. When his ambition and love for visual detail are called upon, Jackson is simply an incomparably galvanic presence, and those are the performances that remind you he stole scenes regularly from the likes of Leonardo DiCaprio, Naomi Watts, Robert DeNiro, Dustin Hoffman, Kevin Spacey, and Geena Davis. And with his new film, Big Game, opening in theaters and VOD on June 26th, we decided to take a look back at Samuel L. Jackson’s most noteworthy performances over the years, in everything from controversial neo-Western revenge tales to big-budget franchise volumes enlivened by his uniquely enthralling attitude.

Django Unchained

The first time we meet Stephen, he doesn't say anything. He eyes Django (Jamie Foxx), riding a horse from afar and immediately sees an issue that Leonardo DiCaprio's sadistic plantation owner hasn't been able to suss out. He sees rebellion, and not only because of Django's questionable wardrobe or the fact that he's riding a horse when African Americans were strictly forbade from doing so at the time. It's his demeanor, the way he carries himself, and Stephen can smell his own. Jackson orchestrates the scene largely through eye moments and those bushy white eyebrows, and when Stephen opens his mouth you can see how he pushes back against DiCaprio's vaguely accepting bigot, arguing about matters of decorum. But it's not until later that Jackson really lets fly in a duo of scenes, one with Broomhilda Van Shaft (Kerry Washington), and another with DiCaprio. With Broomhilda, Jackson hints at a chillingly adept analytical mind that Stephen uses to keep himself at the head of the house, above the other slaves. But as we see in the latter scene, he also uses that intellect to keep cruel, white slaveowners, like his owner, in power, in exchange for the freedom of talking frankly with his employer. It's a performance that fumes with suspicion, paranoia, and violent anger, which Jackson keeps at a remarkably steady boil until he finally faces off with Foxx's gunslinger.

Unbreakable

The last great movie M. Night Shyamalan made is still sumptuously mordent and eerily atmospheric in its view of Philadelphia, but the film's thematic spine comes from the mythology of heroes and villains, specifically in comic books. Jackson's Elijah Price, also known as Mr. Glass, helps Bruce Willis' indestructible David Dunn throughout the film, only to then be revealed as a sort of nemesis, and Jackson never oversells his demonic impulses. In fact, he's more strange and lonely than anything else, and when he realizes the relationship he shares with Willis' character, he weeps with real joy. The hair and wardrobe are admirably eschew and slightly flamboyant but Elijah's final reveal and exchanges with Willis' hero hone in on very real emotions and ideas related to how one finds purpose in a seemingly empty, cynical life. And even though Elijah is clearly a demented psychotic, his final callout to Dunn hints at the sad, resentful human who believes he's found salvation with Dunn.

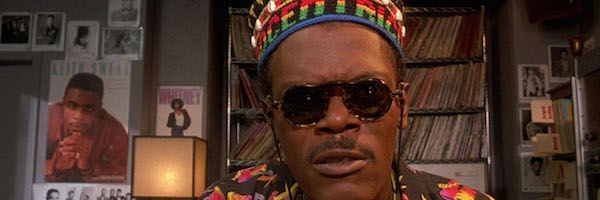

Do the Right Thing

As Mister Señor Love Daddy, the wily DJ that plays soul, rap, blues, and jazz on a Bensonhurst radio station, Samuel L. Jackson offers a backbone to Spike Lee's masterful, radical look at race and money in 1980s New York. Radio Raheem, Mookie, Buggin', Vito, Sal, Mother Sister, and Mayor all seem to bring out electrifying, complex perspectives on not only the troubled neighborhood in which the action takes place, also but how even vaguely sublimated racism can quickly be spurred into action when masculinity or cultural heritage are being questioned. But Love Daddy provides the soundtrack, and also represents the voice of the neighborhood and its people, reporting on local events and ones outside of New York, which, in essence, draws another irrefutable connection between how local problems often have their roots in national or international issues.

A Time to Kill

John Grisham novel adaptations have been a hit and miss affair since they started coming to prominence in the early 1990s. At their best (The Rainmaker, A Time to Kill, The Pelican Brief), they chart the uneasy relationship between personal politics, philosophies, and the legal system. In the case of Joel Schumacher's hugely entertaining A Time to Kill, the question is whether an African American day laborer's (Jackson) murdering of the two men who raped his daughter is justifiable in the eyes of the law. The entire cast, including Kevin Spacey, Matthew Mcconaughey, Sandra Bullock, Chris Cooper, and Kiefer and Donald Sutherland, works on all cylinders, giving viewpoints on any number of thematic interests, but it's the portrayal of the conflicted defendant by Jackson that gives the film its heart. Speaking kindly most of the time in low tones, the character reflects an ugly truth: African Americans are forced to hide their years of anger for acceptance in society whereas white Americans can openly and often violently impose violence on men and women without necessarily having to worry about any consequences. When he yells out "Yes, they deserved to die and I hope they burn in hell!" it's an act of defiance, but Jackson performance registers the immediate fear and regret that follows, knowing how damaging the truth often is when it comes to the law.

Shaft

Jackson was a natural choice for this not-too-shabby remake of Shaft, due to that aforementioned unimpeachable cool. This is all-swagger Jackson, but he doesn't let that define him the way Richard Roundtree did. While dealing with Christian Bale's racist daddy's boy and Jeffrey Wright's psychotic gang kingpin, Jackson's Shaft is all business, and there's specific attention made to the effort put in by him and his team. In other words, he's a more democratic Shaft and though his reputation as a ladies' man is intact, director John Singleton doesn't overplay that hand. Jackson's Shaft is another man at odds with the legal system, but unlike his character in A Time to Kill, this one is conflicted by his inability to get his work done when the law is so easily bought. The demon roiling underneath Singleton's Shaft is the power of money, at battle with the physical work and inventive tactical plans that are needed to undermine millionaires.

Jackie Brown

Ordell Robbie. Even the name is perfect. As is Jackie Brown, the wildly creative crime-melodrama that Quentin Tarantino followed Pulp Fiction up with, and which is very nearly as tightly edited and original as the previous film. At the center of the mishigas that runs the narrative, involving the titular stewardess running drugs and trying to shake off the FBI after they catch her, is Brown's (Pam Grier) relationship with Robbie, a violent pimp and arms dealer. There's a bounty of one-liners traded between the two, but its the quiet moments with Jackson that really sing here. There's a great moment where he's preparing for a murder with "Strawberry Letter 23" blaring out of the speakers, and Robbie making sure every part of his plan and look are tailored. It's a key glimpse at a character who seemingly cares more about image than people, and it further powers his scenes toward the end where personal feelings begin to make him strip away the niceties of his equally sublime and ludicrous appearance.

Black Snake Moan

Now here's one that I honestly don't know how anyone got this made, let alone Hustle & Flow helmer Craig Brewer. An old, poverty-stricken blues man kidnaps and handcuffs Christina Ricci's hot mess to his radiator, intent on ridding her of her promiscuousness and overall bad behavior. As a premise, it's totally ludicrous and borderline offensive but thanks to Jackson and Ricci, the end result is an oddly moving and deeply challenging American film. Jackson's Lazarus could have been a joke, but he finds and evokes a sense of regret and refracted redemption in the scheme, and as the film goes on, his conflicting emotions grow volcanic. The end result is not perfect, or even necessarily good, but Jackson and Ricci's exchanges are so unprecedented and strange that at least this critic couldn't stop thinking about them, days and weeks after seeing the film.

The Long Kiss Goodnight

Mitch Hennessy is one of those characters that Jackson was clearly born to play. A private detective who hires bums to look like his employees and is barely able to buy a nice toy for his young boy, Mitch doesn’t seem to care about the world when we first see him, but he kicks into gear when a housewife (played by Geena Davis), his client, comes to realize she was once a super assassin for the government. This being a Renny Harlin film, explosions, death scenes, and (his wife at the time) Davis are plentiful, but the wild pulse that keeps the film going through the more talky scenes owes a lot to Jackson's wildly inappropriate wise-ass, as well as the consistently badass Davis and a very funny supporting turn from Brian Cox. Sure, Davis gets to say "die screaming mother*cker" but Jackson gets some choice one-liners. If you're not sold on the movie yet, I have no hope for you.

Die Hard: With a Vengeance

There's an argument to be made that Die Hard: With a Vengeance is a better film, pound for pound, than the classic original and Jackson's performance as Zeus has a lot to do with this thinking. There's no denying the tightly wound, tense, and hugely entertaining original, but Nakatomi Plaza is a very specific, isolated realm that’s confined. The third film in the franchise casts New York City as a war zone, with Zeus and John McClane (Bruce Willis) solving riddles and tests of will to try to stop the city from turning into the next Libya. Like the original, problem solving is a main component to the action, mirroring the problem solving that's crucial to filmmaking, whether big or large. Despite this more excited, dangerous landscape, what makes With a Vengeance so much more lively and funny is Willis and Jackson's zippy, foul-mouthed exchanges, which reveal a lot more about McClane's personal life and Zeus's prickly attitude than those useless phone calls Willis had with Reginald VelJohnson in Die Hard.