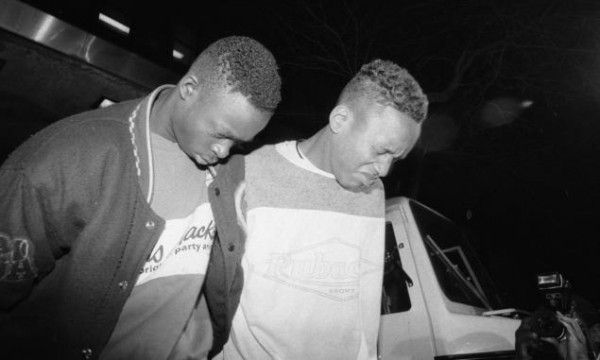

2012 has been another great year for documentary films and The Central Park Five, produced, written, and directed by filmmakers Ken Burns, David McMahon and Sarah Burns, is one of the best. Set against a backdrop of a decaying city plagued by violence and racial tension, the film tells the story of how five young men’s lives were upended by a rush to judgment. In 1989, five black and Latino teenagers from Harlem were arrested and wrongly convicted of beating and raping a white woman in New York City’s Central Park. New York Mayer Ed Koch called it the “crime of the century” and it remains to date one of the biggest media stories of our time.

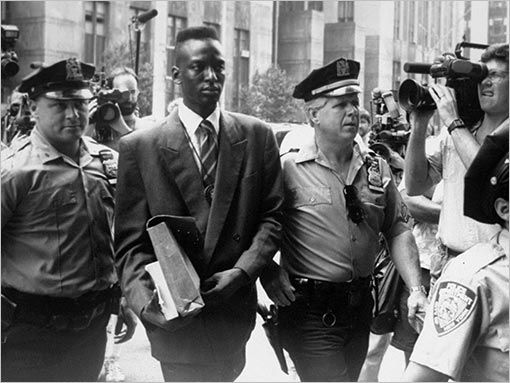

At the film’s press day, Sarah Burns, McMahon, and Raymond Santana, one of the Central Park Five, discussed why the medium of film provided new opportunities for the Five to tell their story in their own words, why the filmmakers are fighting a subpoena from the city of New York for footage from their documentary, how the convictions were vacated in 2002 but the Five have still not been officially exonerated a decade later, and why this story is significant in the context of how we see race in America. Hit the jump for the interview.

Question: Sarah, this project began with you researching and writing your book, The Central Park Five: A Chronicle of a City Wilding. Can you talk about how it evolved into a documentary film?

Sarah Burns: I first met Raymond (Santana) and Kevin (Richardson) in the summer of 2003. I was a college student interning over the summer for this small civil rights law firm, and they were involved in the civil suit in this case which hadn’t even been filed yet. And so, I learned about the case that way. I had been too young when it had happened to be aware of it at that time. I ended up writing my undergraduate thesis about the case. It fit with what I was studying in American Studies. I was just so fascinated by the case and so moved by the story that I felt like that project wasn’t enough to tell the whole story. And so, a couple years later, I came back to it and started working on a book which I spent basically five years researching and writing. And then, pretty early on in the process of working on the book, it became obvious. I don’t even remember the exact conversation, because I think it was something like “What else would we possibly do but make a documentary?”

David McMahon: It’s a family business.

Burns: (laughs) That's what it seemed like. There was really no question about that, and the film provided us with… just the nature of the medium gave us these new opportunities to tell the story in a different way. Even though it tells the same story as the book, it’s very different in many ways. It covers, I think, a more emotional territory and it gives the [Central Park] Five the opportunity to tell the story in their own words, which is a little bit harder to express in the book.

It’s clear in the film that the Five were in Central Park that night, but does the film ever say that they were a part of that group referred to as the wolf pack?

McMahon: I think there’s clarity in the film about the Five. I mean, they all talk about what they witnessed in the park that night which puts them somewhere else from where the assault on the jogger actually happened.

Burns: There were a group of about 30 teenagers in the park that included the Central Park Five. Although some of them at some point scattered and some people left early, there was this group of teenagers who all entered the park together, some of whom committed some other crimes, but none of whom had anything to do with the rape of the Central Park Jogger, and I think that is established.

Was the wolf pack phenomenon something new or had that existed for a long time?

Burns: No, ‘wilding’ was the thing that was really used to describe those activities, but that language came from the police in this case. That was a new idea, and it was something that the police said in their press conference. They ascribed it to the group of teenagers saying that that’s what they’d called their activities, but none of them ever said that they had used that phrase. So, the origin of it is this strange mystery of exactly where it came from. But it really started when the police gave this press conference and said these kids were in the park ‘wilding’ and that became the front page headline.

McMahon: And that’s a word that continues to have resonance in New York. Mayor Bloomberg, as recently as April of 2010, used it to describe the actions of some young minority teens in Central Park. But the other language that was used has echoes of the sort of language that was used in the Jim Crow South and during the Scottsboro Case where we see these terms describing young black men as animals and connecting them to crimes that, in the case of the Scottsboro Boys, they had nothing to do with.

I applaud you for taking on the project and for being a voice. The Five each spent between 6 and 13 years in prison before an unexpected confession and DNA evidence proved their innocence. Why does the city continue to try and ignore what happened?

Burns: Yes, they are now almost a decade into the civil suit. It’s been nine years since they filed the civil suit, and the city has made very clear that they have no intention of settling it, and they are going to go to trial and do everything they can to fight it and are still suggesting that the Five had something to do with the rape. They won’t even go so far as to admit that the prosecution was a mistake, let alone beyond that.

How did the city of New York justify vacating the convictions?

Raymond Santana: That’s it, too. They can’t justify anything and that’s what makes it so bizarre and so weird in that every theory that they propose has so many holes in it. Are you seriously going to take this to trial? And so, we welcome it. That makes it better for us. But, there is nothing, even as far as them saying, “All I did was come into a room and ask Raymond what happened and he told me this story.” You know that’s a lie because the questions took over 30 hours. So, Raymond didn’t just tell you a story.

Burns: Those detectives wouldn’t have been doing their jobs if they had just walked into the room and said, “What happened?”

Santana: Exactly.

Burns: You don’t get to be a detective by doing that. The convictions were vacated by a judge after the defense filed a motion, but the District Attorney’s Office joined in that motion and said that the convictions should be vacated. The official position of the District Attorney’s Office was essentially that they shouldn’t have tried them in the first place, but the NYPD came to a different conclusion. The defendants in the case who are prosecutors and police officers as well as the NYPD and the city as a whole are defended by the city’s civil lawyers called Corporation Council. The position that they seem to be taking is the same as the NYPD’s, which is that even though we know Matias Reyes raped the Central Park jogger, these guys must have had something to do with it somehow, and so, what we did was in good faith basically and we did a great job.

Didn’t the NYPD have a similar case involving a crime committed by Matias Reyes a week earlier?

Santana: Two days earlier.

Burns: They had plenty of opportunity, I think, to catch Reyes much sooner than they did to prevent these other crimes from happening, but they were so convinced that this narrative they had concocted was the right one that they didn’t see.

McMahon: And there was so much momentum going towards it and so much coverage in the press that maybe there was some fear in walking it back and saying, “We didn’t get this right. Let’s start over. Let’s come up with a new theory,” that they couldn’t do that and that’s why maybe today some of these people cling to that original outcome, because in some cases, their careers were built on the success of that prosecution.

This case has been inching its way along in discovery for years. What happens next?

Santana: I don’t really know. We speak to the attorneys. They say we’re getting ready for trial and we’ll go from there and see what happens. Right now, that’s what we’re focusing on. We’ve been ready for ten years now. We’re just waiting on them.

Al Sharpton appears in historical footage in the film. How did he become involved?

Santana: Well Al was a supporter back then.

Is he still?

Santana: Yes. He’s still a supporter. You can ask him about us and he will always support us no matter what. He’s one of the only supporters that we have from back then that’s still around besides Senator Bill Perkins.

Back in 1989, Mayor Koch referred to the rape of the Central Park Jogger as the “crime of the century.” Why did he agree to do an interview for this film?

Santana: He wasn’t a supporter.

McMahon: But when we made those calls to see who would talk to us, we tried everybody from the city. We tried the police. We tried the prosecutors. We talked to two mayors. It was only Koch (former Mayor Ed Koch) and Dinkins (former Mayor David Dinkins) who gave us interviews, and Koch, to his credit, says that he stands with Morgenthau’s (former Manhattan district attorney Robert Morgenthau) decision in 2002, even though there he is on tape [referring to historical footage]. I don’t think he was involved at all with the case, but he got asked questions about it, and you can see in the film what it was that he said about it.

There was an African American reporter interviewed in the film who had some very interesting insights. Who was she?

McMahon: That was Natalie Byfield who was a daily reporter at the time and covered the case. She’s an academic now. She’s terrific.

When you started writing the book and later become involved in making the film, what did you hope to bring about?

Burns: It started out for me as more of an academic pursuit. I was looking for a topic for my senior essay in American Studies, and there was something about this case that seemed really important to understand how it had happened and to understand that it’s not an isolated case, that this reflects a lot of our history, and that this didn’t happen in a vacuum. You have to understand all of the context for it. That was how I first approached it. I did a study of the newspaper coverage and I looked at all the headlines and analyzed them. As I got to know the story better and as I started working on the book and talking to these guys, I think it became much more, for me at least, about getting to know them and telling their story and having this opportunity for them to express their side of the story. That had never happened before. I mean, you had the police and the prosecutor’s version of the story, the press had told this story, but their story – I don’t mean their side of the story or a version of the story, but just who they are and what had happened had never really been told. And so, it became much more about that for the book, and also, especially in the film.

You did extensive investigative research and in-depth interviews for this film. Why is the city of New York now subpoenaing your notes and unseen outtakes? Does this suggest the police and prosecutors did not do their jobs thoroughly in the first place?

McMahon: All the shortcuts for them. We agree.

Burns: They’re fishing. They’re looking for something, anything, that’s dirt they might be able to dig up on these guys who are plaintiffs in the lawsuit. They’re looking for any kind of contradiction or little inconsistency in the story and stuff like that. But we feel as journalists that we have the right to talk to people and not have the government demand to see our work.

Santana: It’s just another stall tactic on their part because they’ve been fishing for ten years now and they haven’t found anything, even on our family members. I mean, they went back 25 years and looked at the doctors that they went to and looked at have they ever been on any disability or social security. None of this has relevance to the case. The truth is that we didn’t rape Patricia Meili and that’s it. For them, it’s another stall tactic to frustrate people and to make us quit or make us give up. But we’ve been here 10 years, so we’re not going anywhere.

Do you think the film is going to have any impact on that?

Santana: Well, that’s what we count on, because for so long our voices were gone, and nobody really got to know us as individuals, as children of New York City, and they gave us this label instead. So now, what we hope is that the film reaches people emotionally and that they connect with us on a whole different level and understand what we went through and that we were victims. Now, we want them to side with us, because at one time they were all against us. Time heals all wounds, and you can forgive and you can move on, and now we want them to just come on our side and voice their opinions about the film.

The elephant in the United States is whether or not we still have a racist society, whether we automatically still put certain people under the bus just by the way they look. When this story attracted your attention, did you see the roots?

Burns: Absolutely. That was the reason I was interested in it, because of its significance in the context of how we deal with race in America. That’s what I was studying and that’s what I was interested in -- the symbolic nature of this case, too, on this larger scale, and that this isn’t isolated and that what happened in this case has everything to do with race. That was the initial reason that I became interested in studying that.

McMahon: And the same suspicions led to what happened with Trayvon Martin or that exists in the stop and frisk policy of the NYPD. It doesn’t make you feel like we’ve moved too far off that position.

Santana: We all come to a point where we’ve got to take a stand. Sarah did that and David did that and Ken (Burns) and us (the Central Park Five) also. And then, you do it also because now you go back and you report the story.