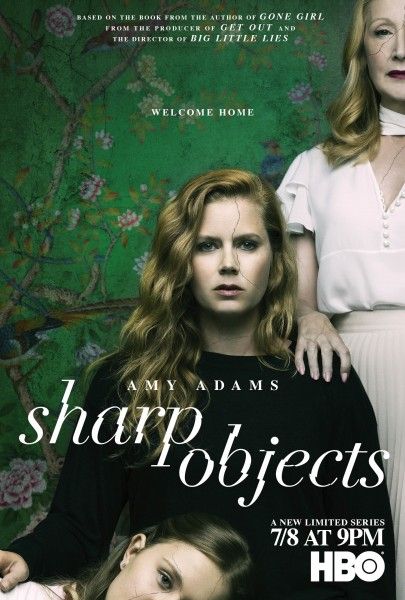

From author Gillian Flynn, showrunner Marti Noxon and director Jean-Marc Vallée, HBO’s eight-episode limited drama series Sharp Objects follows what happens when Camille Preaker (Amy Adams) returns to her small hometown to cover the murders of two pre-teen girls. Trying to understand the crimes puts her in the direct path of her own past and forces her into the line of fire of her disapproving mother Adora (Patricia Clarkson) and her impetuous 15-year-old half-sister Amma (Eliza Scanlen).

While at the Television Critics Association Press Tour presentation for HBO, Collider got the opportunity to chat 1-on-1 with Vallée (who directed and co-edited every episode of the series) about directing Big Little Lies and Sharp Objects back to back, that he feels privileged to work with so many talented women across the two projects, why he likes to take a naturalistic approach to shooting, how the imperfections make a story feel more personal, how they approached shooting the scripts, and that he’d like to take a break and shoot a movie before returning to TV, for a project that he’s hoping to do with Demolition writer Bryan Sipe.

Collider: It’s great to talk to you about this show. It’s such difficult subject matter, but I just think it’s absolutely gorgeous to watch.

JEAN-MARC VALLEE: Thank you!

Between Big Little Lies and Sharp Objects, how has it been for to direct all of these hours of story, back to back?

VALLEE: It’s been a rough, tough ride, physically. I’m very tired. We work so hard and it’s a marathon. It’s really tough. And with this one, on top of that, it’s dark content. To live with it for that long and deal with dead girls and this family, with this history of abuse and violence, it’s tough. But at the same time, it’s great. I love my job. I feel like I’m such a lucky, privileged human being, at a great place. Here I am, talking about what I love. It’s part of the job, and I love it. We talk about what we love to do and create with this bunch of creative people. They all want to do good and they’re all funny. It’s great. It’s powerful. In this art form of storytelling – whether it’s literature, or film, or TV, or theater – stories are great.

We’re in a time when people are really begging for more diversity and inclusion with storytelling and characters, and you’re working with such a wide array of women, of so many different ages and backgrounds.

VALLEE: Yeah. It’s a matter of circumstances, and I’m the privileged one. They’re great actresses and women and people, and it’s beautiful to see them all embracing and developing these projects, as a strong force. They’re the ones behind it, pushing and developing these projects. Amy [Adams] came on board and she came to me. I didn’t pick her, she picked me. She invited me. I feel grateful and thankful to be part of great projects like that and to accompany them in their journey of expressing themselves, in a time when we need it.

Chris Messina told me what an adjustment it was for him to get used to how you work without marks, without lights, without rehearsals, and with only a few takes of each scene. Why is that something that you think works?

VALLEE: I think it’s because there’s a feeling of freedom in the space that we create on the set, without the lighting, handheld, and asking the crew to get out, in order to use the space. That’s one aspect that can put them outside their comfort zone sometimes, but most of the time, it’s the contrary. And since they don’t have a mark, they don’t have to hit the spot to feel the light where they’ll be perfectly lit. The idea is not to have something that feels fabricated, and I think they love that. They love the aspect of just focusing on storytelling and the acting part of storytelling. They’re focusing on acting and reacting to the other actors, instead of reacting to the cameraman that is there. There are only three guys on the set that are not actors – and when I say guys, it could be a woman. There’s the cameraman, the focus puller, and me. Sometimes there’s a fourth guy, who’s the boom guy, but often, we ask the boom guy to get out and we use just the small mics. I’m behind the cameraman and the focus puller is next to me, and we just react to what they do and they learn to react to where we are. We rarely cut. We shoot the rehearsals, which become Take 1. Sometimes, it’s not good, at all, and we start over, with either them or us in different places. We start a scene, and if it’s a three, four page scene, we’re just going to go for 30 or 40 minutes, non-stop. If it’s a shot with Chris, we’ll shoot him, and then we’ll shoot Chris’ POV from behind him. And if he’s with Camille, we’ll respect the difference between the two of them. If I cover the scene from Richard’s perspective, I won’t go close on Camille, unless Camille comes close to Richard, or unless Richard goes close to Camille. We respect the distance. We just do it non-stop, until the cameraman goes, “I need a break,” and until there’s no more memory on the card.

The imperfections really make it feel that much more personal.

VALLEE: Yeah, it feels real. Since we shoot all the time, there’s a sense of imperfection that makes it feel like it’s capture or documentary. We know we’re doing fiction. It’s fiction and we’re staging it, but the staging is set up in a way of capture. They know the scene and have a sense of the scene and where they have to go emotionally, and then I’ll start with the camera here and they figure out where to go, where to sit, and what to. It becomes messy sometimes, and sometimes we don’t have it, at all. Once I see what they do, I react and go, “Okay, I’m going to come here with the camera instead, and I want to cover this from Camille’s perspective and really be on her face, so I’ll be close to her with the 35mm lens and I’m going to follow her and see her face, all the time. And then, I do the opposite and I go behind her because I want to know where she’s going to look and what she’s going to do, and then react to it, in order to design the next shots. When we arrive, we don’t have a shot list. We just create, and I think it has a feeling of perspective, distance, and reality. It’s all about being real and feeling real. When we shot at Barnesville in Georgia, the insects were so loud. They eat the birds. You hear hardly any birds, just insects. It was insects, all the time, and heat. It feels hotter when you hear the insects. It’s loud. And then, there was the sound of the fans and the fans became a visual element. The whole thing is created and fabricated in a way where we don’t want to feel that it’s fabricated. We didn’t want to feel the nice dolly shot and the nice light. We wanted it to feel messy. We move because they move. We don’t move because we move the camera. It’s about them and seeing what they do, and then reacting to that, mainly to the main character, Camille. Of course, I also designed shots from Adora’s perspective and Amma’s perspective, and then, in the editing room, I would decide if the cut would be seen mainly from Camille’s perspective or from Amma’s perspective, depending on where we were in the story and how we needed to feel. Mainly, it’s 70% to 80% in Camille’s perspective.

How did you shoot this? Were you shooting one script at a time, or were you shooting from all of the scripts?

VALLEE: We did Episodes 1, 2 and 3, and then 4, 5 and 6, and then 7 and 8. Sometimes because of Amy’s schedule and the others actors’ schedules, we’d have to bring a scene from 4, 5 or 6 into the first block. And then, we’d shoot the second block, of 4, 5 and 6, and we’d have to bring a couple scenes from 7 and 8 into that block. We tried to avoid it, in order to have continuity. We had a 90-day schedule, and we shot Amy in 65 days. We had to shoot her out in 65, so that gave us some days where we had to [switch things up]. We tried to avoid it because it’s hard for the actors and for us to keep a sense of where we are. We like to be creative, on the day, and as we evolve, the storytelling gets stronger and stronger, so if we start with the end, we haven’t figured out the beginning. We shoot the beginning, and we see how we react and how we get creative with the beginning, and then we can get creative with the middle and the end.

After doing these two shows, back to back, could you see yourself doing another show, you direct every episode, or do you want to take a break from that?

VALLEE: I’m taking a break from that, that’s for sure. I’m going back to features. I want just a two-hour film and a two-hour story. But I have a great TV series projects that’s six hours, unless the writer comes up with more. So far, it’s a six-hour thing. I hope that’s not the next thing because I want to take a long break, and then do a feature film, before I come back to TV. I love doing this. It’s great to take the time to develop characters in more than two hours. To me, it’s the same as a feature film. It’s longer, but the approach is the same.

What is the TV project you’re hoping to do?

VALLEE: It’s called, Gorilla and the Bird, from the book (written by Zack McDermott). It’s Bryan Sipe, who’s a writer that I love. He wrote Demolition, so we’ve worked together in the past, and now we have this new project together. It’s an amazing book. It’s a memoir.

Sharp Objects airs on Sunday nights on HBO.