In the recent New York Times feature on the best 25 movies of the century thus far – picked by A.O. Scott and Manohla Dargis, as well as a handful of directors – it should come as little surprise that Sofia Coppola came in with the head-turner.

In a list that seemed to be at least partially culled from most prominent in her memory, rather than some technical or intellectual reasoning, she included Daddy’s Home, the 2016 comedy that saw Mark Wahlberg and Will Ferrel square off as father and step-father. It’s the sort of movie you casually check in on when it’s running on TV and you’re nursing a mild but persistent hangover.

The filmmaking in Daddy’s Home - courtesy of We’re the Millers and Horrible Bosses 2 helmer Sean Anders - is little more than what you would expect from a multi-camera sitcom. Still, the laughs are real and somewhat frequent, and there was potential for much more. The movie is centered on veneers of masculinity, the familiar manly “types” whose attitudes, political and societal outlooks, and styles are easy to adopt but far harder to escape. A better director and, to a greater extent, a better script could have rendered the comedy an insightful, even intimate portrait of fatherhood and the family unit in 2016, just before a President who seems to be infected with rotten, outdated concepts of manliness took office.

None of Coppola’s movies appear on Scott and Dargis’ admirable, gorgeously antic listicle but on Twitter, Marie Antoinette, the filmmaker’s third film, came up in a thread that Scott started calling for users to share their own picks. He also revealed that the movie constituted the only time that Dargis and he had disagreed to the point of loud, passionate discourse. In her review of the film from Cannes, Dargis accused Marie Antoinette of being one-dimensional and Coppola of being vain in her depiction of the world of the beheaded queen.

This gets at a long-standing argument about the director’s filmmaking, shared by a sizable contingency, whose sumptuous remake of Don Siegel’s The Beguiled hits theaters this weekend: that she is all style. It’s the kind of assertion that is understandable, given the ravishing look and sweep of her films and her meticulous attention to design and composition. It’s also an argument that seems to ignore the symbolic power of veneers, and Coppola’s careful, probing criticism of putting all of one’s faith in appearances and, yes, styles.

This is apparent from early on in her luminous and haunting adaptation of Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Virgin Suicides, in which the mysterious Lisbon sisters become the far-off obsession of a group of male classmates who barely speak to them once or twice. The boys are bewitched and imagine futures with the girls, who must obey the strict religious and “moral” doctrine of their overbearing mother, played brilliantly by Kathleen Turner in an inspired bit of casting. They like the appearances of the sisters and what they stand for – innocence, adventure, understanding, sex, and lord knows what else – but they are too cowardly, too obsessed with their ideas of them to get to know who they really are. Their naiveté, reflected in James Woods’ devastating portrait of the flighty Lisbon father, is seen as only one of a few reason why the sisters decide to take their own lives at the end of the film.

This tendency to force confrontations between tailored façade and the unknowable inner workings of women and men only got more radical and daring as Coppola continued to make movies, beginning with the now classic Lost in Translation. Though the melancholic relationship that buds between Scarlett Johansson’s lonely bride and Bill Murray’s distraught actor is not nearly as grave a situation as suicide, the restrained desire between them is no easy matter. Their thrilling chemistry and Coppola’s imaginative portrait of modern-day Tokyo, a country famed for its unique, traditionally delicate view of aesthetics in art and design, cast a dazzling spell but their loyalty to the worlds that brought them to their meeting constantly interfere or simply interrupt their electrifying connection. Perhaps it’s the good in them that ultimately makes them not to (audibly) reveal how they feel about each other, but it’s also caution and fear of how the next step would look.

That’s not even a quarter of what’s going on in Lost in Translation but there is a clear questioning of what the characters’ relationship could be defined as. And Coppola’s response to all this is that there is almost always more going on than what the first glance suggests, whether one happens to think that Johansson’s character has daddy issues or Murray’s character is chasing his evaporated youth.

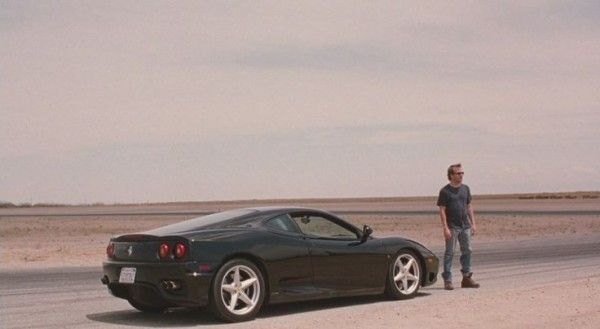

Somewhere, in contrast, is a literal father-daughter melodrama and remains the director’s most daring and audacious work. The sketch of the story – Stephen Dorff’s celebrity dad looks after his adoring teenage daughter for a few days – provides a bare-minimum backbone for what becomes a cascade of potent symbolic images, sparse yet meaningful exchanges, and giddy, beguiling glimpses at the intimate life of a rich, famous actor in the beginning of a decline. There may in fact be no more representative image of Coppola’s work than that of Dorff being left to sit under a mask mold, with nothing but his breathing to suggest he’s still there.

Again, the set-up means to hint at a simplistic vision of a dead-beat father and his innocent, talented child but Coppola mines it for what Roger Ebert once referred to as “Ma” moments, derived from Japanese. When Elle Fanning, a revelation in the role of the daughter, Cleo, sits down to breakfast with her father and the Italian woman he came home with the night before, notice where Coppola focuses. She puts emphasis on Fanning’s gaze at both the woman and her father, evoking feelings of confused jealousy, curiosity, and disappointment all in the same moment with little more than arbitrary chit-chat for sound. She keeps her face just poised enough to not give her feelings away to the woman, but for those looking, it’s clear as day.

Dorff’s action-hero type also has a lot more going on than just a need to chase women and a general interest in the movie business. He’s in need of a real hit but in no real trouble of losing his money, and in brief exclamations, one can see an ambitious artist attempting to breakthrough and become something serious. His frustration over his limbo-like station in life, both professionally and personally, is a mirror image in his daughter’s own inner confusion about becoming a grown woman, weathering what seems like a horrid divorce, and a father who at least appears to treat women flippantly. The scene in which Cleo does a figure skating routine also suggests the first bud of a career that can also end in vulgar celebrity despite its origins in graceful technique and artistry.

One might concede that the characters in The Bling Ring have no real technique or artistry to their crimes but that would miss an important aspect of Coppola’s fifth film. From the outside, the film is a polemic about the emptiness of millennial taste and the age of social media, which sounds insufferable. Coppola isn’t entirely unmoved by the psychological effects that the internet can have on teens – look at that haunting last shot of Emma Watson’s Nikki – but she’s not convinced it’s made them empty or entirely careless.

Coppola depicts the real-life gang of West Coast teens that openly stole from the homes of the rich and famous as in search of identity through their clothes, accessories, and cash since their own lives haven’t produced more obvious role models. In a memorable scene, Nikki and her sisters are forced to recite a passage from The Secret, a rigid, ridiculous guide on how to exist, with their mother (Leslie Mann), and that alone should tell you why kids flock to Instagram. And beyond that, the director uses the film to fairly consider the charges of her being a vain filmmaker by making the search for style also a serious criminal offence in this particular situation. The Bling Ring may indeed be Coppola’s darkest work, though The Beguiled, which I’m still processing, may give it a run for its money ultimately.

This brings us back to Marie Antoinette, in which Coppola essentially does something similar to what Martin Scorsese did in The Wolf of Wall Street. She denies neither the thrill and comfort of wealth nor the personal and societal damage that is done by keeping the wealthy entertained and bloodlines in power. For all the grand flourishes of decadence that Kirsten Dunst’s titular queen demands and enjoys, the whole of France is rotting outside. There are no scenes of revenge or much in the way of seeing the gruesome end of her husband’s kingdom, nor is there much in the way of seeing the impoverished masses.

To infer that Coppola does not understand the criminal injustice of what Marie Antoinette did, however, is frankly ludicrous, as the movie even slowly shows how the increase in her material wants, at the cost of her personal sanity and happiness, coincides with an increasing amount of flashes of impending death and society’s disdain for her and her husband. Coppola doesn’t outwardly resent Marie Antoinette for what she did, and that seems to be the issue at hand. To simply resent her and to make the film primarily about the corruptive power of money, however, would to simply take the popular view of her, what everyone sees when they hear her name. Coppola’s goal is to understand the character with her faults entirely intact without making her life about those faults. And like Scorsese’s film, it doubles as a robust and self-deprecating criticism of a life of a major filmmaker, who is given absurd amounts of money as a person and on the job to produce a few hours of entertainment.

Sure, some of those entertainments are also works of art but they must also be entertaining and involving, at least on the surface.