[Editor’s Note: Welcome to “Stream This,” our weekly feature where we single out television programs and movies of considerable merit that are available on Netflix, Hulu, Amazon, Crackle, or other streaming services.]

The first thing we see is a naked boy, standing in a small basin in the middle of a grand room in luxurious mansion. A moment passes before his mother comes to him and delicately helps him wash, while speaking gently to her son. There's a stirring intimacy to the scene - the fact that he is in water suggests something like the communication between mother and son in the womb. Physically, they are loving and as close as a mother and son can be, but the words that begin to come out of the mother's mouth quickly turn ugly - fear, disease, racism, and distrust are what she imparts to the boy as he stands there in total vulnerability to his mother. There are many striking sequences in Martin Scorsese's The Aviator, but when all is said and done, we will return to this moment, when the seed was planted and the pain first started.

What the mother said is something like gospel to the young Howard Hughes, and though it doesn't really show itself in total until about halfway through Scorsese's stunning opus, it's always roiling beneath Hughes' increasingly erratic actions as he blooms into an adult. There's a parallel here to the filmmaker himself, who was brought up a Catholic and remains one to this day - he rather famously refused to tell James Lipton his favorite curse word and cited his religion as the reason. Like Hughes, who is played by Leonardo DiCaprio after the opening scene, Scorsese's ambitions as an artist have continuously ran against the doctrine that he was given when he was young. In a way, The Aviator is about running away from the person your parents made, and the limitations of such struggles.

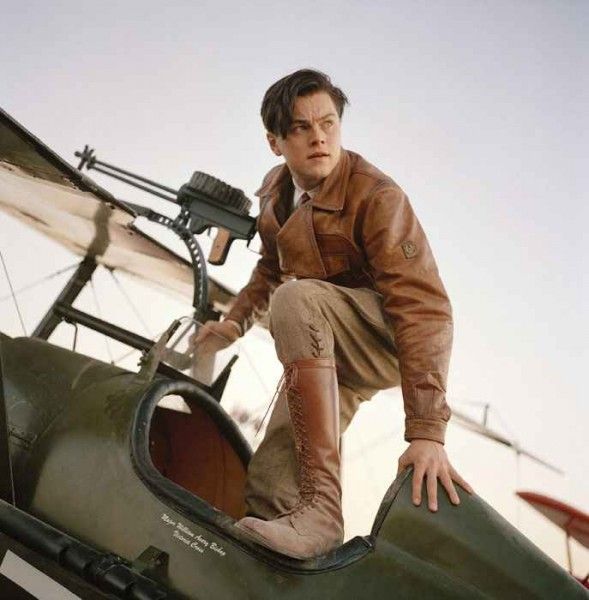

When we first meet him as an adult, Hughes is making his infamous Hell's Angels, and unlike most young filmmakers, his problem is that he has too much money. His endless wealth allows Hughes to do ridiculous reshoots, as well as insist on ridiculous production design, way too many cameras, and the best technical equipment money can buy. There's a lot of technical talk in John Logan's script, particularly about cameras and airplanes, which stresses a thorough knowledge of the mechanics of his particular talents as much as his intuitive sense of design and style. His ambitions in these realms, however, make him a perfectionist, and we watch as his need for more and more specifications nearly lead him to exhaust his vast fortune. In one of the biggest laughs of the movie, Hughes demands Hell's Angels be made into a talkie only minutes after his first screening of the film, much to the chagrin of his CEO, Noah Dietrich, played by John C. Reilly.

Hughes is portrayed and written as an artist of tremendous vision, working in film not unlike a God creating his own world - in relation to Scorsese's faith, the title of the 1930 picture becomes particularly fascinating. His ambitions and imagination are boundless, leading to innovations in cinema and flight that were ahead of the times, but his mother has imprinted him with a deep sense of limitations in regards to his health and, to a lesser extent, morality. Later, in another riotous scene, Hughes attempts to get scientific and mathematical in explaining his clear obsession with Jane Russell's breasts when defending The Outlaw, his follow-up to Hell's Angels. These conflicting sensibilities, as Scorsese presents them, are what ultimately drove Hughes crazy, his obsession with cleanliness and the look of all things mirroring a sense of control that he can't find in his art or, eventually, in his business as a aviation magnate. His inherent distrust of the filthy, germ-ridden world outside of his control, outside of his fortune, fuels a sense of self-control that he's consistently at war with as an artist.

And like Scorsese, Hughes' colleagues and lovers are largely famous people, from Cate Blanchett's Katharine Hepburn and Kate Beckinsale's Ava Gardner to Jude Law's Errol Flynn and Stanley DeSantis' Louis B. Mayer. His portrayal of Hollywood is boisterous and lively, as is the director's depiction of Hughes and Hepburn's love affair, which nearly led to marriage, but what's most intriguing is the look of the entire film. There's an almost desaturated color to Scorsese's compositions and though the imagery is consistently vibrant, bordering on ravishing, the ultimate look of the film is something like colorization. Here again, Scorsese finds a radical way of reflecting Hughes' sense of purity: if black and white silent pictures are seen as the purest expression of the cinema's power, colorization would be seen as a corrupted form, an attempt to rewrite the very language of the film's aesthetic.

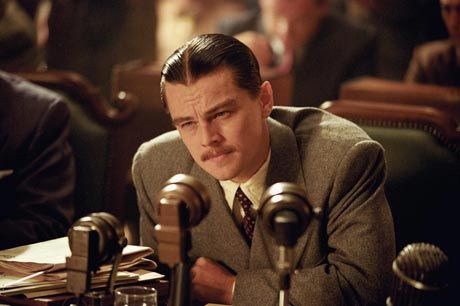

Logan's script makes for plenty of narrative to chew on, from Hughes' own aviation tests to his relationships with Hepburn, Gardner, and a poor stand-in that he employs to his battle with Pan Am honcho Juan Trippe (a terrific Alec Baldwin) and his henchman, Senator Ralph Owen Brewster (Alan Alda), but the film is anchored by DiCaprio's take on Hughes. One can see similarities between this performance and his equally astonishing performance in Clint Eastwood's magnificent J. Edgar, but the areas where the performances differ are important. Where control was a cold code of discipline for Hoover, Hughes' sense of idiosyncratic detail is passionate and messy; his obsession with control looks an awful lot like total instability. Where governmental authority gave Hoover a way to repress his personal desires, a need to suppress barely hidden by a role that required widespread suppression, DiCaprio's Hughes is using artistic rule to express the torrent of violent feelings that his childhood led him to restrain.

It's one of the actor's first great performances, many of subsequently came from his work with Scorsese, and when he catches Hughes caught between his erratic, painful inner-life and his professional, artistic career, stuttering in repetition, he evokes emotional frustration and madness at a sobering, furious timbre. Indeed, in the film's final moment, the haunting reality of being a visionary tied inherently to the fear and guilt of the biblical past comes shining through as clear as day.

The Aviator is currently available for streaming on Netflix. I'll be back with another Stream This next week.