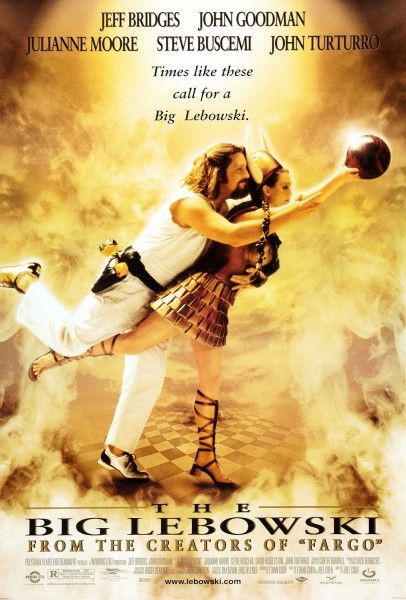

The Big Lebowski was not a hit movie when it was released. Despite being Joel and Ethan Coen’s follow-up to their award-winning Fargo, it actually made less at the box office, earning only $17 million (it’s not that Coen Brothers movies are depressed at the box office; two years later, O Brother, Where Art Thou? would earn $45 million and become a music sensation). And yet time and fans have been incredibly kind to The Big Lebowski, leading the unique comedy to be a bona fide cult hit that’s instantly quotable (personally, I can’t pass a rug store without saying, “It really tied the room together,”) and always hilarious.

The film also speaks to how the Coen Brothers maintain their sense of identity without becoming stale or predictable. The safe move after Fargo would have been to do either a much bigger movie, using their newfound critical success to go mainstream, or perhaps just do something in the vein of Fargo—macabre humor, bumbling criminals, and an ode to human decency. The Big Lebowski has some of these aspects like Walter biting off a nihilist’s ear and the nihilists being generally incompetent, but no one would call Lebowski a Xerox copy of Fargo.

Instead, Lebowski is a much stranger movie, far more comfortable with the comically absurd. That absurdity is one of the trademarks of the Coens’ filmography, and they can use it to political ends (Burn After Reading), religious doubt (A Serious Man), artistic frustration (Barton Fink), or, in the case of The Big Lebowski, a detective yarn. At its core, The Big Lebowski is about a profoundly lazy man having to do something difficult and failing repeatedly. It’s genius.

It’s almost as if the Coens looked at the deeply competent Marge Gunderson and thought, “How can we keep this character likable, but do a completely 180 on everything that makes her good at her job?” And thus you have The Dude, a guy who doesn’t really care about justice, who just wants his rug back, and yet, through sheer luck and repeat mishaps, solves the case all the same. But Dude doesn’t refute or undermine Marge as much as his behavior showcases a different kind of decency.

One question I keep coming back to with The Big Lebowski even though I’ve seen it countless times is, “Why does Donnie have to die?” Even the movie seems to question this decision as The Stranger comments that he didn’t much like it when Donnie died. I’ve come to the conclusion that Donnie’s death serves two purposes. First, the ashes gag is one of the funniest things the Coens have ever done, and that’s saying something. But more importantly, because without it, you could get to the end of The Big Lebowski and think that Dude’s laziness also makes him selfish. After all, Dude never goes to the cops about Bunny’s disappearance even when it looks like she’s had a toe cut off, and only consults the cops after his car and the briefcase are stolen. Donnie’s death shows that for all of his laziness and incompetence, Dude is fundamentally a good person who cares about his friends. Granted, Jeff Bridges’ unforgettable performance would have done that as well, but the script always comes first with the Coens.

The fact that we can still twirl around these questions with The Big Lebowski in addition to quoting it endlessly shows that even though Fargo is the more “respectable” of the two features, The Big Lebowski stands right alongside it. It’s just as memorable as the Coen’s Oscar-winning feature, and while it may not have the same level of prestige, the Dude still abides.