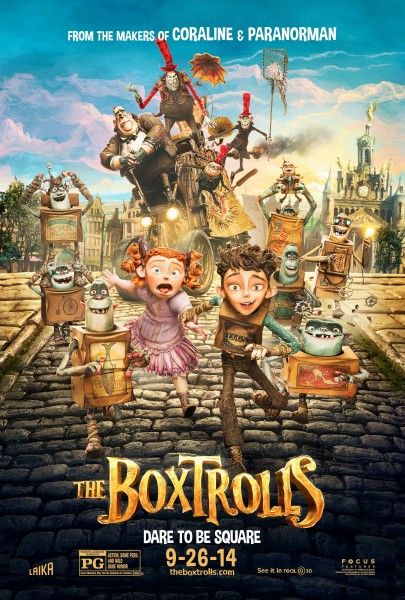

Travis Knight, The Boxtrolls producer and lead animator who worked on LAIKA’s first two groundbreaking movies, ParaNorman and Coraline, loves the 100-year-old art form and is always looking for bold and innovative ways to take it to places it’s never been before. While ParaNorman and Coraline were contemporary American stories told with shadings of supernatural elements, The Boxtrolls is a period piece mashup of detective story, absurdist comedy, and steampunk adventure with a dark Dickensian twist. Opening September 26th, the beautiful stop-motion 3D animated film features an extraordinary cast that includes Sir Ben Kingsley, Isaac Hempstead Wright, and Elle Fanning.

At our roundtable interview, Knight discussed how animating in stop-motion is less about patience than the ability to focus your imagination intensely for long periods of time, why it’s crucial to find the right voiceover actors who can bring believability to the characters and emotional authenticity to the performance, why he wants to make thought provoking, emotionally resonant, and enduring films rather than pop-culture confections, his childhood inspirations for dynamic storytelling, how the film’s 3D elements were designed from the beginning to bring the best aspects of technology into this hand-crafted world, the funny bit in the end credits, and his next awesome project. Check out the interview after the jump and please note there are some spoilers.

You must have some of the most amazing patience to bring a film like this together frame by frame?

TRAVIS KNIGHT: It certainly takes a special kind of person. It’s funny, I don’t really see it as patience, although you would have to have that on some level just because you’re churning out maybe four or five seconds of footage a week as an animator. I mean, yes, you have to be patient. If it takes you nearly ten years to make a movie, you have to be pretty patient, but I don’t see that as the foundational thing, the most important thing of what we do. For me, it’s less about patience than it is about the ability to focus intensely for long periods of time when you imagine a puppet. I never get bored when I’m animating. While maybe I get through two or three seconds a day, it’s a constant challenge in your head. It’s almost like a mathematical formula or a chess game. You’re always trying to figure out how you can get your puppet from point A to point B, and so there are all these different little bits. You’ve got to figure out how their arms and legs are moving, what’s going on with the hair, and what’s going on with the eyes. You’ve got to figure all this stuff out and hit your marks, but then it can’t look mechanical. It has to feel alive and look like it’s a real living, breathing thing. And so, it’s mentally very challenging to work through all that kind of stuff. And then, it’s physically demanding too because you’re contorting your body on these sets in all kinds of weird positions, and you’re hurting yourself and bleeding and everything else. So, there’s always something to keep you on your toes. It’s deeply satisfying when all that stuff comes together and you see it come to life in a way that makes it feel like it’s not a doll, but it’s actually a living thing. That’s what we all shoot for – to make these things feel alive.

Can you talk about the conversations you guys had about how scary and intense this could be and how far to push those elements?

KNIGHT: We’re certainly not trying to traumatize any children, and I think we’ve probably failed on that front. When I think about my favorite films growing up, the kinds of films that I loved, the classic Disney films, things like Snow White or Pinocchio, or later, the kinds of films I loved growing up in the 80s like the Amblin films, things like E.T. or Goonies, that kind of thing, they all shared in common this really artful balance of darkness and light, of intensity and warmth. It was a little bit spooky in places where it needed to be, and fun and entertaining in other places, balancing heart and emotion with intensity. For me, that is just good, dynamic storytelling with lots of ups and downs. You can really feel the elation when you’ve gone through a little bit of pain. That was something that defined filmmaking for families for generations. It’s only within the last 25 years that a lot of that stuff has been muted. It’s been tamped down. It’s fine. Those things are entertaining, but I think they also don’t mean much. When you don’t have a big up and down, where everything is in

that drizzly little center, everything is kind of muted. I don’t think you can have much of an experience that gives you much to think about or much to feel. We want to make films that are thought provoking, that are emotionally resonant, that are challenging, enduring and stand the test of time. They’re not little pop culture confections, those little bits of ephemera. And so, that gets to the core of it. Coraline was one kind of film. It was a dark, modern fairytale. Because of that, because of its influences, it had to be scary in places. In ParaNorman, it was this comedic, supernatural thriller, and it was rooted in some of those great Hammer horror films and horror films from the 70s and 80s. And again, because of the inspirations of that story, it had to have some scary elements. This film is a different kind of a story. It’s our first period piece. It’s kind of an absurdist Dickensian coming-of-age story. It’s a different kind of a story which didn’t necessarily call for scares, but it did have to have some intensity in places. And so, I don’t think Boxtrolls is a scary film, but there are moments that will keep some people on edge and kids in particular. But I also think that’s a good thing. Obviously, we all need to know our children and what they can handle. We make films for families, and we give opportunities for families to connect, and I’m very proud of that. But we don’t make little babysitters, like something you can plop your kid in front of and just turn off their brain and they sit there. We want people to engage in our world.

[SPOILER ALERT]

I don’t want to give this away, but your ending with your main character is not something traditionally we would see.

KNIGHT: They usually fall to their deaths or are redeemed in some way.

I applaud you for not being afraid to go that way.

KNIGHT: But he also dies in a kind of silly way.

Of his own doing.

KNIGHT: Yes, it’s his own choice.

Can you talk about casting your actors who were largely British and having Elle Fanning use a British accent?

KNIGHT: Because of the source material, we decided to set the film in this fake, Dickensian world, this Victorian world, and it meant that, for that kind of authenticity, we wanted British actors, by and large. Virtually everybody we cast is a British actor. But more important for us than where someone came from is the emotional authenticity they bring to the performance. The film was kind of a two-hander – you have your female protagonist and your male protagonist. Then they get together and we see what happens when that happens. We had our male protagonist, Eggs, in Isaac Hempstead Wright, who’s just an extraordinary young actor. Then, for the female lead, we wanted the best young actress in the world. When we started thinking about it, we thought, “Well clearly that’s Elle Fanning. There’s nobody better than Elle Fanning right now in the world.” It was odd because six, seven years ago, who was the best young actress in the world? It was Dakota Fanning. We’d actually met Elle years and years ago when we were working with Dakota. Of course, the problem there is that she is not British, but she had done a handful of roles in Great Britain at the time, and she had developed that muscle. She could do the accent. But again, more important was the emotional authenticity she brought to the role. She could absolutely do the accent, and there was a dialect coach in the studio, and whenever we thought, “Yeah, that worked,” the dialect coach was like, “No. That’s not right.” Of course we have a big British contingent in our crew. There are a lot of people from the U.K. that work with us, and so when they bought off on it, it was like, “Okay, yeah, this works.” But she’s a great actress. The best there is.

And then, Tracy Morgan was the other American actor. He didn’t even try to do a British accent. It was like, “All right, we’ll just accept it.” But it was funny because I remember originally he was like, “I’ve been working on my British accent, guys!” And then he would just do his standard Tracy Morgan stuff, and it was like, “All right!” He’s like this Victorian Terminator, Tracy Morgan’s character, and it didn’t matter what his accent was. He was just a tough guy.

We were incredibly fortunate to get the actors that we got, because in an animated film, it really is all about the voice. The actors have so many tools at their disposal when they’re in a live-action film with their face, their body, their voice. When you only have your voice to convey emotion, it’s tricky, and a lot of great actors can’t do it. So the people that we got are exceptional at that. We listen to the voice and disconnect it from what we see on screen. When we cast, we always take clips from interviews so we can see how their voices naturally sound without putting on a role, and then we pull clips from TV shows or movies that they’re in so we can hear how that sounds. You want all those voices to occupy their own space in a sonic spectrum and then see how they play off each other or against each other. Virtually every single person we went out to said, “Yes,” so we had an extraordinary group of actors.

LAIKA movies harken back to a different era of animation while also being incredibly progressive. With so many films in the marketplace, what makes this one special and why do it in 3D?

KNIGHT: I think stop-motion is one of the oldest forms of filmmaking there is. It’s been around since the dawn of cinema. It’s as old as film itself. In some ways, the process hasn’t changed in 100 years when Georges Méliès was sending rockets to the moon. It’s still essentially the same thing. You still have a puppet on a set with real lights and a camera that the animator is moving frame by frame to get a performance. What we’ve done to dramatically move the art form forward is we’ve integrated technology into the mix. We’ve brought in rapid prototyping, laser cutting, digital stereoscopic photography, and all these other things in all these different departments to essentially embrace the author of our demise. In the ‘80s and ‘90s, the computer was rising up and stop-motion was falling out of favor because the computer could do anything. It could do anything, and stop-motion could only do a few things. And against that, we had to come up with a new way to justify even using this medium. There’s no reason to use it unless you could use it in an interesting way. So we thought that, like a Luddite embracing the loom, if we could take the best aspects of technology and bring it into this hand-crafted world, we could have something that was really unusual, that had a different feel, a different vibe, a different sensibility, and felt unique in this world where everything is done in the computer. I think you have a sense of that. When everything is artificial, when nothing is real, when there’s no objects bathed in real light, I think audiences know, and it has a different feeling. So by being able to integrate those things together, we can take the medium to places it’s never been before, to really enhance this hundred-year-old art form and do something interesting, something that audiences don’t typically see.

3D stereoscopic photography, I think, is just another tool in a filmmaker’s toolbox. You can use it to tell a more immersive story, or you can use it as a cheap cash grab. I think a lot of folks have used it as a cheap cash grab and put it as a little layer on top at the end, after they’ve shot it, where it was never intended to be shot in 3D. They just do it because they think they can get a few extra shekels out of the audience. For us, we design it right at the outset. Just like you write a script or do a color script for the design, we do a 3D script where we decide this is where we ramp up the 3D for emotional impact, this is where we play it down for this reason. So we shoot wedges. We have the whole thing plotted out before we start, and like sound or light or lens choice or color or anything, it’s yet another way we can use a tool to bring the audience into the film. Or you could use it as a gimmick, but that’s not how we use it.

What inspired the funny bit we see in the end credits where the characters are watching the animator and commenting on the process?

KNIGHT: (Laughs) That was me. That was the very last shot of the film. It’s the last shot in the film and it’s the last shot that we shot. I was the last guy out there, and everyone else was wrapping up and done and moving onto the next thing, and they were like, “Hurry up, hurry up, hurry up!” It’s funny because if you go through it frame by frame, you can see those days where I had a meeting because I was wearing a collared shirt, and then those days where I could just focus on animating because I’m wearing a T-shirt. I got more done those days. But every film that we’ve done, we have a little button somewhere within the credits to just highlight this was how it was done. On Coraline, we had the way we brought the little mice circus to life and the things swirling around. You could see all the rigging and everything. It’s just a reminder for people who are interested in the process that this is how it was done. In ParaNorman, we show how the puppet was made. On this, we wanted [to show] these two guys who were somehow redeemed over the course of their journey and what they’re up to now. And then, they start to philosophize about the meaning of the universe and these two idiots are talking. It was a way to give a nod again to the process, but also to show an aspect of their character. We just thought it was a fun little bit. We’d scripted it all out, and then when the actors, Nick (Frost) and Richard (Ayoade), were in the studio, they just started riffing. A lot of that stuff they came up with on their own. It took three weeks I think for me to shoot that.

What are you working on next?

KNIGHT: Something awesome. We have a minute in the can on our next film, so we’re almost done. See you guys in two years.