[To mark the 10th anniversary of The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, we’re reposting this deep dive into the work of director David Fincher. This article contain spoilers.]

Across his filmography, David Fincher's work has been noted as dark, foreboding, chilly, cynical, cutting, and irreverent. The Curious Case of Benjamin Button is a striking anomaly in his filmography as the allure of the project makes some sense, but the execution is a lush, unabashed romance bubbling with mawkish sentiment. The movie is graceful, beautiful, poetic, and yet oddly distant. The whole production feels gilded as Fincher made a deeply moving film out of a fairly terrible script. The most curious thing about The Curious Case of Benjamin Button is how it manages to be a tearjerker despite its craven desire to elicit emotion from a director who rejects sentimentality.

In an interview in David Prior's excellent The Curious Birth of Benjamin Button documentary (which is longer than the movie), Fincher says he was attracted to the project because he wanted to make a movie about death since his father had recently died. He explains that being at his father's deathbed was so much more profound than having a child. "You want it to be over as quickly as possible," says Fincher, "and yet you don’t want it to be over." This led to him wanting to tell a story about "Love measured against this graph paper of something we try so desperately to ignore."

That's a really lovely sentiment (aside from using graph paper), but yes, love and death are intertwined as they give each other meaning. However, Fincher says that unlike Brad Pitt, he didn't see Benjamin Button as a love story. He saw it as a "death story", and not a tale of co-dependency. And at the end of the documentary, he says (half-jokingly), "I don’t want to see anybody together. I want to see everybody as unhappy as me. Everybody in this movie dies. That’s how I was able to stomach the rest of it." Cate Blanchett describes Fincher as a cynic, and although I've never met him, as I've stated before, I don't think his work is purely cynical. That being said, I think the love story in Benjamin Button is one of the most powerful yet completely disingenuous I've ever seen.

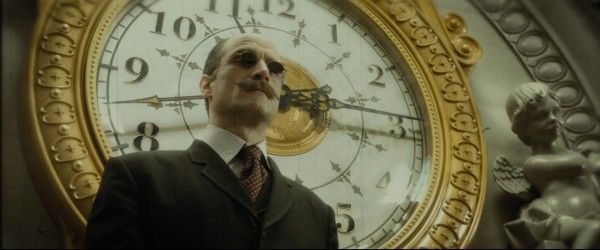

The "death story" is where Fincher's heart truly lies, and the movie begins with that attitude. The first shot is Daisy (Blanchett) lying on her deathbed in New Orleans, and Hurricane Katrina is bearing down on the city. The following scene is the allegory of Monsieur Gateau (Elias Koteas), a blind man who lost his son in World War I, and made a clock that ran backwards to represent the hope of bringing back all those who died. A blind man makes a pretty, heartfelt sentiment, for something that can never happen, and then sails off into nothing where he dies of a broken heart.

This is not the most uplifting way to begin your movie, but it's also filled with a romanticism that pervades the entire picture (such as having a gigantic symbol of a clock running backwards in a movie where the protagonist ages backwards). That's part of the intriguing and frustrating paradox of The Curious Case of Benjamin Button—you have a cynic trying to make a romance, and working furiously to stay true to his belief that this is a movie about death and regrets when the script is nothing but life lessons and platitudes.

For Fincher, it's not that this movie has to be a funeral dirge even though the cinematography is steeped in his traditional dark color palette albeit tinged with amber, gold, and other warm colors permeating the scenes outside of Daisy's deathbed and the conclusion of Benjamin's life. Benjamin Button is trying to sing a ballad with the bittersweet and melancholy undertones, but there's almost no support from a storytelling perspective.

Based off the F. Scott Fitzgerald short story, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button has a very simple premise: a man is born old and dies young. In the movie, the being-born-old part is surprising and oddly miraculous, although his age is completely superficial. Benjamin (Pitt) is not born wise. He just looks old and has a child's mind. This leads to misunderstandings both comical (going to a brothel with Captain Mike (Jared Harris)) and painful (being chastised by Grandma Fuller (Phillys Somerville) for his late-night rendezvous with young Daisy (Elle Fanning)). But he still has to learn everything like the rest of us, and the nature of his condition doesn't drastically change his life experience. Growing up in an old folks home and surrounded by natural causes of death is an unusual but not radical experience. He's seemingly different, but easily relatable.

We're meant to accept death through its most romantic interpretation. When the soldiers in the Gateau story fall in battle, it's in vibrant, slow motion without any limbs getting blown off or bloodcurdling cries of pain. When Benjamin goes to war, everyone who dies on the ship has digital blood-spatter, but nothing gruesome (even all of the blood coming out of Captain Mike is digital). If not for Daisy, death in Benjamin Button would always be some noble passing. At its most ideal, death can come peacefully, but it's not the only way, and Benjamin Button would choose to ignore that reality as much as possible.

That's the hollowness of Benjamin Button. It doesn't want anything to be untidy when love, death, and regret are inherently messy. When Benjamin decides to decline having sex with Daisy on their first date as adults, he narrates "Our lives are defined by opportunities; even the ones we miss." Except it's not really a missed opportunity. A missed opportunity implies something is lost and gone forever. A more accurate line is "Our lives are defined by opportunities; even the ones we delay." Even Fincher doesn't feel that Benjamin and Daisy are soul mates. From the commentary track:

"I’ve always maintained—and there are people who feel differently—that the movie is not about how two people are made for each other. It’s about two people who loved each other and made a commitment to one another and then lived up to that internal, and maybe not even voice, but that commitment to one another from the first time they meet on the lawn and he’s eighty and she’s seven. Never mind tension that these are two people who are made for one another. It’s someone who should spark an interest in another person and continue to sort of parallel one another throughout life."

Not exactly a love story in the most romantic terms despite being shot and told as a romance. In this retrospective, I've usually sided with Fincher's interpretation of his work, but there are times where I feel his intentions don't match the execution. While I don't want to let him off the hook for the flaws in Benjamin Button, I admit his investment in every technical aspect is immaculate, but also a distraction. Yes, the visual effects for Benjamin's appearance are a marvel, and while they have (no pun intended) aged a bit, they're still impressive. This is in addition to Claudio Miranda's gorgeous cinematography and Alexandre Desplat's magnificent score. The picture does everything right except abide by its own expectations or honestly tell its story.

The retelling of Daisy's accident is like a condensed version of all the movie's strengths and weaknesses. Kirk Baxter and Angus Wall's editing strings us along as we're told by Benjamin about how you can chalk life up to chaos or predestination, but the end result is always the same. The scene is lyrical, tragic, and moving. It's also shatters the storytelling device. There's no way Benjamin could have known about all of the events leading up to Daisy's accident. He speaks about these events with utmost certainty rather than adding a disclaimer along the lines of "perhaps this happened." The message of the scene is also fairly hollow: If things had happened differently, things would be different. No kidding.

That's the phoniness of Eric Roth's script, which cripples the entire movie. I'm shocked that Fincher would let so many platitudes and pieces of heavy-handed dialogue run through the movie. Queenie (Taraji P. Henson) tells Benjamin, "You never know what's coming for you." Later, Benjamin is told, "When it comes to the end, you have to let go." Benjamin later points out, "God keeps reminding me I'm lucky to be alive." These are the kind of comments you needlepoint onto throw pillows. Additionally, as was pointed out around the time of the movie's release, Benjamin Button shares more than a few similarities with Roth's script for Forrest Gump:

Even Fincher acknowledges the similarities as he points out on the commentary that the feather in Forrest Gump is not like the hummingbird in Benjamin Button. He sees the hummingbird as the antithesis of Forrest Gump, and while I understand that the hummingbird represents infinity and the feather represents—I have no idea (I haven't seen Forrest Gump in well over a decade)—that doesn't change all of the other similarities between the two movies. But where The Curious Case of Benjamin Button really gets under my skin is how it not only lets Benjamin off the hook for abandoning his family; it applauds him for it. Yet again, I'm shocked at how a self-professed cynic like Fincher could miss something as brazenly selfish as Benjamin's flimsy decision to leave Daisy and Caroline. Because the movie can't lose its romantic sheen, it won't honestly acknowledge his decision. Benjamin lacks the awareness to realize that he's abandoning his daughter just as his father abandoned him.

This decision is awful in so many ways. Instead, his decision to walk out on his family is predicated on the notion that Caroline "needs a father, not a playmate" as if it were impossible to explain that her father has a unique condition that causes him to age backwards. It's not like he has to go to school with her. It would be like saying there's a genetic illness in the family, and rather than stay, he will spare them the trouble. Except in Benjamin's case, nothing will debilitate him from going out in the world and experiencing life to the fullest. Benjamin may "regret" leaving Caroline, but the film never calls him on it for being extraordinarily selfish. Instead, the dying Daisy tells Caroline that Benjamin was right and it would have been impossible to take care of both of them even though she still takes care of Benjamin at the end of his life. "I'm not that strong," says Daisy, which is a surprising statement from someone who figured out that just because she could no longer dance professionally, she could still be a dance teacher instead of giving up her passion entirely. If she has a weakness, it's that she found a husband to raise Caroline, and while she says she loved him, he was never as important as Benjamin. What a great way for that unnamed character to spend his life—being second to an absentee father, and then his wife cheats on him when Benjamin saunters back in looking even hotter.

None of this is played as deeply fucked up. Fincher locked us in so firmly into the notion that we were in a grand romance about life, love, and death that nothing can shatter that illusion. And here's the kicker: It worked on me. Against my better judgment, I was crying at the end, because I like the idea of what the movie wants to be. For all of his consistency as a perfectionist and as visual stylist, Fincher keeps pushing himself to try new things. He cited Zodiac as something he had never done before, but it felt more organic to his filmography than The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. This is the film I find it hardest to reconcile with his body of work. His next movie would be his most powerful, accomplished, and enduring picture.

Other Entries:

- The Work of David Fincher

- Alien 3

- Se7en

- The Game

- Fight Club

- Panic Room

- Zodiac

- The Social Network

- The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo

- House of Cards and the Director's Future