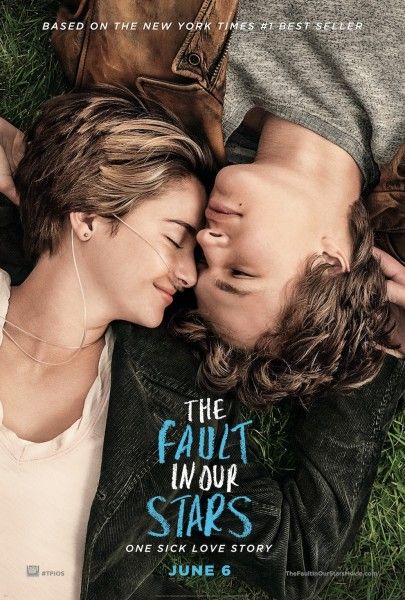

The sweetest film ever made about existential nihilism, The Fault in Our Stars under the pretense of tween YA adapted romance smuggles in a heavy dose of post-Kierkegaardian philosophy. As such the film’s sort of a scam job – advertised with its pretty cherubic young actors’ faces with the promise of an epic doomed love story (a la well… Love Story) but actually more interested in what life means when everything you do is inherently meaningless and how can you possibly leave a mark in a world where inevitably everyone you know (and more importantly everyone who knows you) fade away into infinite nothingness. All those date-night kids didn’t quite know what they were getting themselves in to. Hit the jump for my The Fault in Our Stars extended cut review.

Take the title, a partial quote from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, Cassius confiding: “The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves that we are underlings.” FOS demonstrably refutes the notion – for Hazel (Shailene Woodley) & Gus (Ansel Elgort) the fault 100% lies in those goddamn stars. Choice has nothing to do with it – Gus and Hazel didn’t choose to have terminal cancer, didn’t choose to live a life one step from the grave leading to an unavoidable hospital bedside demise. It’s not surprising then that much of the narrative thrust of the picture (besides the couple’s evolving courtship) relies on Hazel’s obsession with discovering what happens after the end of her favorite novel – also not-so-coincidentally about a young girl dying from cancer. That her obsession later leads to a meeting with the author of said book (the casting of Willem Dafoe as the writer should tell you all you need to know), wherein he – the author – proves to not only be a drunken ass but also oblivious to Hazel’s query, highlights the bleak uncertainty Hazel (and by proxy all of us) so steadfastly seeks to know but never will. Because it is without a doubt that Hazel, you and I will at some point die; but it is very much uncertain how anybody will react to the news. Will the newspapers/internet/TV cover it? How many people will be at the funeral? For how long will loved-ones grieve? There’s really no way to know because Hazel/you/I simply won’t be there.

Sure casting the author as a proverbial ‘God’ figure (an absentee and belligerent one at that) is perhaps a tad on the nose; but it does the job in getting the message across. It also then shouldn’t be surprising that Dafoe as Author-cum-God in drunken half-formed theological musings basically spells out the whole point of the picture in ten minutes of screen-time.

After Hazel wistfully inquires what happens to all the characters at the end of his novel (the aptly-titled An Imperial Affliction), Van Houten (Dafoe) puts on some blaring form of Swedish pop-rock music, opining obtusely “The important thing is not what nonsense the voices are saying, but what they’re feeling.” He’s attempting to draw a parallel between Hazel’s question and the music itself – the surface value of both (the lyrics and Hazel’s inquiry) unimportant. For Hazel isn’t really interested in what happens to the characters in Van Houten’s book, her query a projection of her own uncertainty about how those around her (her mom, her dad, Gus) will deal with and live on past her own impending death. It doesn’t really matter what ‘nonsense’ Hazel is saying – but what she’s feeling.

Van Houten further elaborates with a seemingly non-sequitur parable. “Let’s imagine you’re racing a tortoise” he says, “The tortoise has a ten yard head start. In the time it takes you to run ten yards, the tortoise has moved maybe one yard and so on forever. You’re faster than the tortoise but you can never catch him you see. You can only decrease his lead. Now certainly you can run past the tortoise as long as you don’t contemplate the mechanics of it all. The question of ‘how’ turns out to be so complicated that nobody really solved it until Canter’s proof that some infinities are bigger than other infinities.”

In his own condescending, oblique way – Van Houten answers what he believes Hazel really wants to know: what is life after death - not just for the person who dies but for those he/she leaves behind? In the parable, the tortoise is death and we, humanity, are constantly encroaching upon it, decreasing the lead – racing to our own impending mortality. However you can’t catch the tortoise in that you can’t ever conquer death; but you can pass the tortoise in that even after you die, you live on in other people’s thoughts or memories or in more tangible forms like a book or song or words or art or historical impact. Of course some people’s ‘mark’ (look to such ‘timeless’ figures as say Thomas Jefferson, Plato, Mozart…) is greater than others (your next door neighbor for instance). Some infinities are bigger than others indeed.

Gus himself is adamant on living an “exceptional life”, of leaving a mark, of being talked about and celebrated for decades to come. The inherent tragedy of the character contingent on the slow realization that he will not live long enough to achieve such lofty aspirations – cancer (the stars) robbing him of such an opportunity. When Hazel eulogizes a sickly Gus, she does so repurposing Van Houten’s words “Some infinities are greater than others… But Gus, I’m cannot tell you how grateful I am for our little infinity.” The oxymoron “a little infinity”: a rejection of sorts of the importance of immortalization, a big middle finger to the void and cloud of death that surrounds Gus & Hazel. Yes – they are doomed to die and inevitably be forgotten and everyone will continue to love and struggle and die just like before and now and later and always; but it’s the moment that counts, this moment, their moment – together.

Towards the end of the film, a much more empathetic Van Houten reappears to give one more cryptic life lesson. He asks Hazel if she is familiar with the ‘trolley problem’ – an ethics and philosophical experiment, the gist of which can be surmised thusly: a runaway train zooms down a track, ahead of which five people are tied up onto. On a secondary track, parallel to the first track, one person is tied up. You stand by a lever. If you pull the lever, the train will switch tracks and kill the one man. However if you do nothing, the train will continue on its course and crush the five people. What is the correct action to take?

Hazel interrupts Van Houten before he can finish his thought; but the point Van Houten is driving at isn’t which option (to let five die or to kill one) is right, but the inherently terrible condition upon which the experiment is based. The person by the lever didn’t ask to be put in this unwinnable situation. They have no power over the train or the number of people on each track. The situation they have been borne into is unfair and unjust – much like the situation Hazel and Gus have been borne into. Circumstance is the unbeatable enemy here.

“You don’t get to choose if you get hurt in this world, but you do have a say in who hurts you…” Gus’s final words in the picture repurpose the trolley problem on a less literal, more spiritual level. No matter if you pull the lever or not, someone is going to die, someone is going to be hurt. Your options may be limited and the outcome unavoidable (the train will kill someone, the cancer will take Gus and Hazel’s lives) but those small moments, those small choices – to love, to go to Amsterdam, to wake up in the morning: those are the choices that define Gus and Hazel and everybody else for that matter. Just because life is inherently meaningless, just because the end is already written in stone doesn’t make the choices you have pointless – if anything, it makes them more important, for they are the only thing you have control over. To pull the lever or not – becomes the only source of free will in a predetermined life.

When Hazel stares up at the stars in the opening and closing of the film – it isn’t just some tween romantic gobbledygook but an act of rebellion. Sometimes when staring into the void, the only course of action is to tell it to fuck off.

*Of note: the following essay was written after having seen the Extended Cut of Fault in Our Stars – but if I’m being honest, there isn’t much of a difference between this new cut and the shorter theatrical edition. I noted a couple additional scenes: Hazel explains her condition to a small girl (author John Green cameos here as the girl’s father), Hazel and Gus flirt over selling a swing set, a couple beats in the picture seem to be held longer – but for the most part there are no noticeable changes. The added moments neither detract nor add anything to the picture. Take of this, as you will…