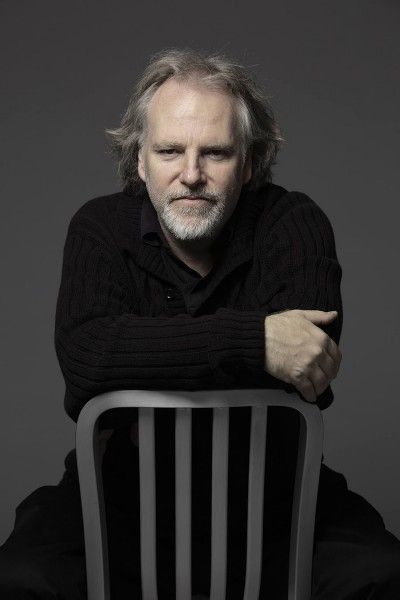

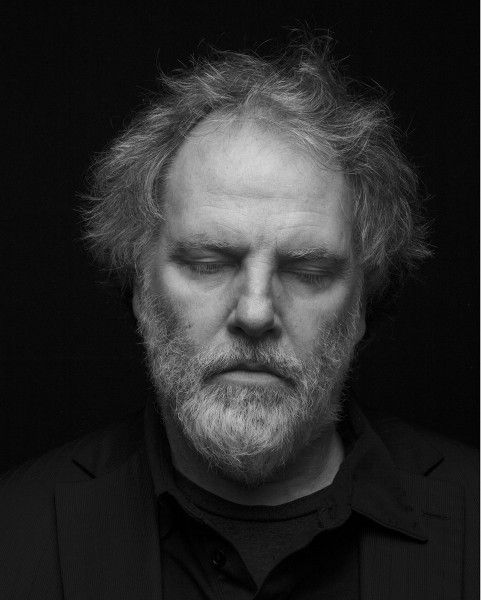

Where to even start with The Forbidden Room? The latest film from cinematic maniac Guy Maddin (My Winnipeg) is his most colorful, most insane visual orgy yet, marking what is possibly the Canadian auteur's magnum opus. As an off-shoot of his interactive Séances project, the 59-year-old director enlisted his former student Evan Johnson to co-direct his latest feature film, stitching together vignettes inspired by lost films of the past. With a cast of familiar faces that includes Charlotte Rampling, Mathieu Amalric, Udo Kier, Caroline Dhavernas, and Maddin regular Louis Negin, Maddin and Johnson used styles from the silent cinema era (a common thread in Maddin films) to tell stories of submarine crews relying on flapjacks for air, evil banana boyfriends, a woman whose bones are broken and reset, and a man with an ass fetish, inspiring a hysterical musical number about a derrière, composed by Sparks.

Collider sat down with the filmmakers to unpack some of the madness behind The Forbidden Room. Oh, and also minions and flapjacks.

COLLIDER: Nice to meet you!

GUY MADDIN: Let's do the handshake again. Sometimes it affects the rest of the interview. I'm determined to get it right.

Oh good, yeah. I dated a guy once I called "Salmon Hands."

MADDIN: [Laughs] Did you ever get past the handshake stage with him? Just flopping.

No comment. I appreciate a good handshake is what I'm saying. Sorry, that was a TMI opener.

MADDIN: No, no, strangely, I asked Darcy Fehr—who played me in a couple of my movies—to quickly make a movie in which all he had to do was slap two salmons together. He did it, trooper that he was, and told me half an hour later that he was allergic to salmon. He was asking for antihistamines.

That's dedication! Anyway, congratulations on The Forbidden Room. It's honestly in my top three films this year.

MADDIN: Oh wow, thank you so much! Did you say top 300?

Yeah, it's like 299.

MADDIN: Thank you just the same!

I’m familiar with your style but I was just silently screaming through the entire movie. It was hysterical and wild and I had no idea where it was going to go next. How do I start [laughs], how, why?

MADDIN: When. Let’s start with when. [Laughs] We started shooting three years ago in Paris at the Centre Georges Pompidou, and then we finished shooting it two years ago at the Phi Centre in Montreal. But “why?” is magical question. [Laughs] The Forbidden Room started as an Internet project. I’d made 10 feature films and I felt more or less good about the trajectory of my career. I’d had some some setbacks here and there, [and a little] backsliding, but for the most part I felt good about what I’ve made. But I’d watch my French distributor, ED Distribution really carefully arrange interviews for me in such a way that they knew which reviewers liked watching a preview in the morning, which in the afternoon, which ones liked a cappuccino which ones liked a back rub, and in the pre-Internet wave they always seemed to get the most batches of journalists who had the most potential to be Guy Maddin appreciators… Once I realized I was addicted to the Internet and couldn’t get myself off of it that what they did in years of hard work of finding an audience for me, could be done, almost overnight with an Internet project that every potential person appreciator of the stuff we make could be found relatively quickly without the back rubs and cappuccinos.

I had this project in the back of my mind for many years. The idea of adapting the stories of lost films—as if they were sacred texts—and presenting them like Bible stories but told in our own words. I asked Evan to be a researcher on it pretty quickly. He started thinking in conceptual terms of ways that expanded the project in really sophisticated ways. And we became co-creators with the state-funding bodies in Canada who are aggressively trying to support new media Internet projects. But, truth be told, there just isn't [enough] money behind it without [turning the project] into a feature film, as well as an Internet series… So we conceived them as companion pieces and shot them at the same time, and so they do have some material in common. There is way more material for the Internet project, hours more, hundreds of hours more. But our hearts devoted themselves to the feature with equal love. We were very careful to make It would never be the perception that one was created to be in the service of the other, they're companion pieces. So right now we are talking about the feature film and the longer Internet project will launch in 2016. We might make another feature film from a bunch of those “lost films.”

When you say “lost films” are these damaged films you’ve recreated?

MADDIN: They’re films that once were and no longer are. Ernst Lubitsch’s The Patriot, which was even nominated for an Academy Award, was lost somehow. With these recreated films, either all the prints of were destroyed in fires or they were lost in shipping mistakes or people just lost track of them or them incorrectly until they turn into dust or jelly. 80% of films for the first four decades of film history are lost. And that’s just American films, in other countries it’s much higher: in Japan it was 98%, in the Philippines 100%—but then one was found recently; the Soviet Union was really high. In doing our research we were astonished to find that almost every country in the world, with the exceptions of those in the continent of Africa, and Antarctica, had film industries.

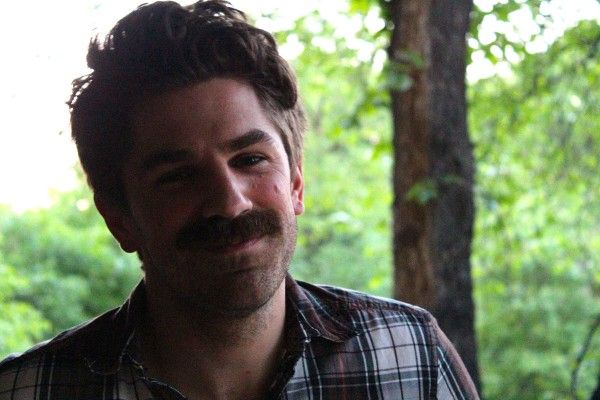

EVAN JOHNSON: With South Africa’s film industry, it was just mining propaganda, right?

MADDIN: Right

JOHNSON: Colonial mining propaganda.

MADDIN: Yeah.

JOHNSON: Which is a genre of film itself.

MADDIN: Yes. It turns out that we discovered genres we didn't even know existed and so it was really fascinating to research. So in their historical context, they all sound really exciting but they didn't exist anymore, so to recreate the idea of them we just had a title and maybe a synopsis. In the case of American films, Variety has been around since 1902 or 1903 and so they’ve been offering up reviews and synopsis almost since the beginning of film. The same within England, there’s press that’s accessible. But in other countries they're lost. But then we started expanding our definition of what a “lost film” could include, and we began to include films where the filmmakers themselves got lost before they could make their films, like Jean Vigo died at age 29 before he could make some, so we got a list of his unrealized films and I contacted his daughter Luis Vigo and we shot one of his unrealized films (for The Forbidden Room). Then we started to include films by marginalized peoples in various countries, for instance from Cambodian filmmakers that were murdered in the 70s by the Khmer Rouge, and early African American filmmakers and female filmmakers from countries that did not support their works. We were surprised at how many women directors there were in the first couple decades, before they got pushed out of the way as the industry grew.

So there are all sorts of different types of lost films, they're lost for different reasons, and different ideologies that were really popular. The research has created a sense for me of the 20th century as a century of pop cultural advancements through loss.

Did you and Evan meet while working on My Winnipeg?

JOHNSON: Sort of, I was the camera guy. I didn't have much to do with the making of My Winnipeg. I shot some of the material for it. I was [Guy’s] student before that.

Oh you were?

MADDIN: Yeah, maybe when he was 19.

Oh cool. And then you brought him onto co-direct this with you.

MADDIN: Evan just started helping me more and more and more; he started as a research assistant on this. And I don't know, we liked watching movies together, and I learned a lot of stuff from. It’s been like reverse parenting. My daughter raised me [laughs], now I have granddaughters raising me and my student is teaching me things [laughs]. It’s kind of pathologically troubling but it’s just my path. I’ve just kind of done everything backwards my whole life.

Were there any disagreements or challenges working together for so long?

MADDIN: Evan is very direct and I found it very bracing and so if he disagreed with something I said, he would just tell me... Generally, if a Canadian really hates something they'll say it’s “pretty good”, and if they really like something they'll say it’s “pretty good” [laughs] and there’s just a slight difference that even Canadians have trouble telling, so you circle around each other with so much dishonesty and sick ass misdirection that it’s really nice to just hear, “Nah, I don't think so…” So if there was an argument he’d have his point A and I’d have my point B, and we would usually arrive at a point C—which was actually an improvement on both of our original positions.

You think Canadians are usually passive aggressive?

JOHNSON: Yes.

MADDIN: Yeah. [Laughs]

JOHNSON: Not all of them.

MADDIN: No, I'm terrified of many assertive Canadians.

Well we think Canadians are very friendly, maybe they're just good at hiding it.

JOHNSON: No, they aren’t that friendly.

MADDIN: They aren't that friendly, maybe just slightly more polite than Americans, but they seem less friendly than Americans to me.

JOHNSON: I agree.

This is your most colorful film. Why’d you take that approach?

MADDIN: Well I really wanted to dive into the digital world with guns blazing. Evan really helped there because I've been in so much awe of color, really respected the power of color and how it can shape a narrative and shape atmosphere and you just cant put a color up there and without thinking about it and so I suppose I’ve been very wary of working in color. Also as a poverty filmmaker it’s just cheaper shooting a black and white, not because the film stock is cheaper—which it was a little bit—but because your art department doesn't need to make decisions about color, and you don’t need props to be a certain color, because it would just turn out grey. So there was money to be saved but I was becoming exhausted by everything I had to say in black and white. I wanted to work in color, and I felt that this was the time to bring out all the color pallets that I could think of.

But a lot [of the coloring] was done by Evan in post. I just loved his intuitions. We saved a lot for post because we want to give each narrative its own look. We wanted to give the viewers a chance to figure out where they were if that’s’ even possible.

Can you tell me about your fascination with the body and the disassembling of the body? I see it in several of your films. The bone-breaking in this one, of course, is the one that comes to mind.

MADDIN: The bone-breaking thing is something that I put in many narratives. In many relationships that I've had people just try to own the other person. It reminds me of Vertigo a bit when Jimmy Stewart takes Kim Novak out and insists on dressing her up his way. It just strikes me that a couple of bone-setting brothers [laughs] would insist on breaking and re-setting a woman's bones.

JOHNSON: Also the villains in that narrative are skeletons. I know [Maddin] likes it when a film can be condensed down to a single image or an interplay of images. This is the spine of the film. When we were writing that script, we thought that every scene had to be bone related or we’d lose coherent metaphorical coherence or something like that and you do that with a lot of things.

MADDIN: These are little fairytales, so they have to have a tuning fork moment. You know and bones.

There were so many moments I loved, and I think my favorite part was probably “The Derrière Song” [laughs]. Is it original music?

MADDIN: It was Evan who suggested that we try to include as many genres as we could, but we realized that we hadn’t shot a musicial, and while it comes off like a rock video, it was conceptualized as a musical number. It’s a story that was once a lost Greek film about a man who was driven insane by a sexual obsession.

JOHNSON: The title of the Greek film was The Fist of a Cripple.

MADDIN: One of the most incorrect titles [laughs].

JOHNSON: We applied it to another story we came across where a man feels this sexual desire that he can’t control so he has brain surgery to fix it. It felt insufficient to deal with sexual obsession for a section of the film, but brain surgery felt vastly over-sufficient.

MADDIN: I think in the final script he was basically just going to be a fist, with some nerve endings, floating in space. Usually my musical scores are more soupy, ambient and abstract. We needed something bouncier and so I asked these musicians that I know, Ron and Russell Mael of the pop group Sparks, who have been recording albums since 1970. we gave them the plot points and within a few hours they delivered a 16-track pop song about derrieres. I think it will be online as a single, with the video from the movie.

My other favorite thing was the boyfriend that turned into a banana [laughs].

MADDIN: Apparently it’s a part of the Filipino vampire mythology. It’s just you and you're bitten by a vampire and then you slowly rot and decay. You smell sweet like an over ripe banana and then you finally just turn into a blackened banana.

Oh wow.

MADDIN: Like you get to have some mischief before you’re basically a blackened banana, impotent, and nothing to be afraid of.

So this was from a Filipino film?

MADDIN: Many, many Filipino vampire movies were made and lost. Many continue to be made. Winnipeg, where I work the most, has a very large Filipino community. So at one point I had 85 Filipino children in my apartment with their parents and I said, this movie is going to be about the aswang myth and they all shrieked, “the aswang!” I got the accent on the syllable wrong every time but everyone knew it. It’s very well known and I guess there’s a big, pulpy Filipino vampire movie industry there.

Random question, have you seen Minions?

MADDIN: No, is that a kids show? My granddaughters know all about it, and they will point and shout, “Look at that Minions hat! Look at that!” B I don’t know what it is.

Oh, they are a spin-off from Despicable Me.

JOHNSON: They are little assistants to villains of some kind right?

Yeah, and they are just obsessed with bananas.

MADDIN: Oh, I didn’t know that.

They just become this most contentious thing in pop culture, and these decayed bananas reminded me of the Minions.

MADDIN: How come? Why is it contentious?

Because people come up with theories, like they assisted with Hitler during the Holocaust and all these Internet jokes.

MADDIN: Oh, because they can be applied to everything.

Do you want people to reach deeply into your movies? Do you think much about how your imagery will be analyzed?

MADDIN: I’ve always had a dream that people will really like the movie, and maybe find little rhymes or echoes within their own lives somewhere.

JOHNSON: It’s also not the easiest for an average moviegoer…

MADDIN: Well, then we are getting into the territory of my wilder daydreams.

JOHNSON; I’ve lost touch with why The Forbidden Room is so difficult. We made it, we understand everything , but you know we were involved in every little decision that went into making it. To us it probably appears totally logical and coherent, and simple, and fun. Because you know it was designed to sound good, and to look good, like what else do you need? But it’s obviously a bombardment, confusing and unpleasant for some people.

MADDIN: Yeah even some of our close friends have.…

JOHNSON: Told us they hated it. But I had the time of my life. [laughs]

Since they save lives in your film, how do you eat your flapjacks?

JOHNSON: [Laughs] I use a lot of syrup for mine.

MADDIN: I eat mine on the exhale [laughs]. Evan’s father is a nuclear physicist, by the way. He informed us that flapjack bubbles actually contain carbon dioxide, not oxygen.

Really?

MADDIN: So that’s why I now exhale [laughs] while ingesting them.

The Forbidden Room opens on Wednesday, October 7 in New York City with select cities to follow.