[With Mindhunter set to premiere next week, we’re reposting our deep dives into the work of director David Fincher. These articles contain spoilers.]

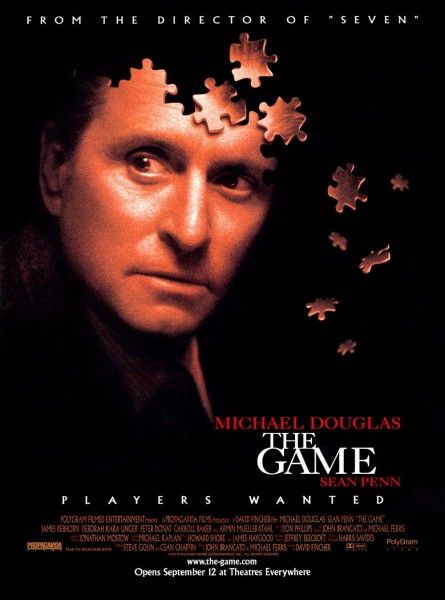

Se7en is a dark, brooding film focusing on the nature of sin. It's atmospheric, beautifully shot, and thoughtfully constructed. Unfortunately, The Game was a painfully disappointing follow-up where Fincher's cynicism provided too much of a gap. The movie has the veneer of something cathartic and exciting, but whereas the darkness of Se7en had an nasty, beating pulse, The Game was a limp mish-mash of ideas that still managed to culminate into something thoughtful, but the thought was unrewarding when compared to the other movies Fincher would make in most of his other movies. Se7en was a huge step forward, but The Game was an awkward retreat into the basics of filmmaking rather than a glimpse into the soul of its shallow protagonist.

Beginning with the world's WASP-iest home video of a ridiculously unhappy birthday party, we're quickly informed that a depressing childhood has been further marred by a father's suicide leading ultimately to a son's isolation. Nicholas Van Orton (Michael Douglas) is in the process of rebirth as he puts on a watch commemorating his 18th birthday while barely paying any attention to the fact that the day is his 48th birthday. When he gets a surprise call from his brother Conrad (Sean Penn), it's a reluctant celebration with his closest living relative. For Nicholas, it's better to be withdrawn.

The purpose of Nicholas' character is to discover he not only needs other people, but also that he has to start living his life. It's A Christmas Carol meets Wall Street minus any sympathy whatsoever. Set aside the fact that we're supposed to be rooting for an investment banker. Even Fincher doesn't really have as much interest in Nicholas beyond setting him up as a pawn and trying to do it as quickly as possible.

When Nicholas arrives at CRS, it serves a dual purpose: humbling Nicholas and setting up CRS as an ultimate power. Nicholas is told the process will only take an hour, and it ends up taking the entire day as he's poked, prodded, and even assaulted with disturbing images. CRS claims these tests are to ensure that the game is tailored specifically to Nicholas, but as viewers, it's to let us know the dominance of CRS. Fincher shoots their office more like a hi-tech prison as frosted glass chambers informs the inmate that something's happening on the other side, but he can't make out what and he can't get out.

The movie is gorgeously shot (something I could only appreciate once I watched the movie on Blu-ray), and in its own way, it's as oppressive as Se7en and Alien 3. Fincher loves soaking his movies in darks that eat away the corners of the frame. Soon after the "game" begins, Nicholas is at his country club, and even the locker room is closing in on him. It gets to us on a subconscious level so we're already on edge when we see something as overtly creepy as the clown puppet, which is found in the same place as his father's body.

There’s a lot of menace in The Game but never much threat. Nicholas’ unease keeps coming from the notion that he’s not really playing a game except he should always know he’s playing a game. If anything, he’s getting the full package: adventure, romance, mystery, and the follies of a youth he never had. We can tell that Nicholas Van Orton is someone who never got in trouble a day in his life because he had no choice. He had to fill his father’s shoes, and so Conrad got to be the irresponsible one.

“What do you get for the man who has everything?” Conrad asks Nicholas when he gives him the gift of the game. The answer is you give him everything because Nicholas is the audience. Fincher explains on the commentary track:

The Game is a movie about making movies. It’s not about Nicholas Van Orton. It’s not about him coming to grips with his father’s death. And even though on the commentary track John D. Brancato and Michael Ferris say it was Fincher who pushed the script in more of a “Scrooge” direction, it’s not about Van Orton really learning from his mistakes to become a better person. There’s no wrong he has to right at the end of the movie beyond whether or not he’ll take one more leap of faith and go on a date with “Christine” (Deborah Kara Unger). That’s an underwhelming achievement at best.

Fincher’s real focus is on the power of CRS. Like with John Doe, Fincher is enamored of an artistic antagonist who can expertly lead an audience wherever they want that person to go. CRS is a movie studio filled with actors, stunt doubles, set dressers, special effects designers, etc. It’s just the notion of what if a movie was designed for one person. We’re not meant to identify with Nicholas. He’s not an everyman. He’s too rich, too removed, and too alone. This is why you cast someone like Michael Douglas instead of someone like Tom Hanks.

The design of the The Game is immaculate, and its individual elements are there to remind us of how well every puzzle piece looks. I flat-out hated The Game on my first two viewings, but as I’ve said, the eye-popping Blu-ray transfer (approved by Fincher) for the Criterion Collection gave me a newfound appreciation for the movie’s visuals. In addition to how Fincher drenches the movie in darkness and low lighting, everything is staged perfectly: the chase scenes are claustrophobic and twisting like a maze. The scene in Christine’s cabin is perversely cozy. Fincher notes in the commentary how he hates the color red in movies. And yet you’ll notice that Christine’s bra is bright red—sexiness and arousal you can't miss. Admirably, these elements are heightened not in a crass way to pander to the audience, but rather to work as road signs. It’s a magician breaking down each of his tricks and telling you how they work, and that’s interesting to a point. But as an audience in the middle of watching a movie, we’re interested in the journey and we want to be fooled. And on a first viewing, Fincher can get away with it. We can get lost in Nicholas’ journey, but the movie only works once because it has nothing deeper. Nicholas isn’t an interesting character and the resolution of his journey isn’t about catharsis. It’s about how the game concludes. As Fincher notes in the commentary:

“This film, for me, was an interesting study not in human behavior—how people relate to each other, what people want from life or career or any of that. It was, “What does an audience want or expect or need from a film?” My question was, “How much will they put up with, and will they go for 45 minutes of red herrings?”

For me, the climax of the The Game is a dead giveaway that the movie couldn’t care less about any emotional impact. First, Nicholas’ jump is meant to echo his father’s suicide, and his landing his supposed to be a moment of catharsis where he realizes that he doesn’t have to repeat the mistakes of the past. Then everyone in the room applauds him even though he just tried to commit suicide.

If that moment puts the movie on life support, then the following line absolutely kills it. When Nicholas goes around greeting his guests, he goes to “Jim Feingold” (James Rebhorn), who says, “Thank God you jumped, because if you didn’t, I was supposed to throw you off!” The Game isn’t about Nicholas making a choice. It’s about making sure he hits his mark. But maybe I’m being overly harsh, and I will say now that I don’t always agree with Fincher when it comes to his thoughts on his movies. However, I will quote the following line from the commentary:

“This isn’t a movie about real life. It’s a movie about movies.”

Fincher’s movies can be cold, but The Game is absolutely frozen. Thankfully, his next feature would explode with life and hit us as hard as he could. Next: Fight Club Other Entries:

- The Work of David Fincher

- Alien 3

- Se7en

- Fight Club

- Panic Room

- Zodiac

- The Curious Case of Benjamin Button

- The Social Network

- The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo

- House of Cards and the Director's Future