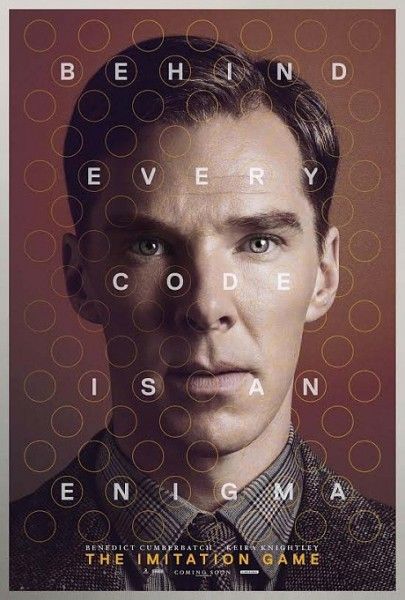

As we move into awards season, 2014 is proving to be an exciting year for films and no doubt there will be some year-end surprise contenders. One of my personal favorites is The Imitation Game, directed by Norwegian filmmaker Morten Tyldum, about British mathematician, cryptanalyst and war hero Alan Turing (Benedict Cumberbatch) who is credited with cracking the unbreakable codes of Germany’s World War II Enigma machine. Opening November 28th, the film’s intense and haunting portrayal of a brilliant, complicated man offers a fresh take on the biopic genre and features an impressive cast that includes Keira Knightley, Matthew Goode, and Mark Strong.

At the Below The Line press day, we sat down with Producers Teddy Schwarzman, Nora Grossman, Ido Ostrowsky, Production Designer Maria Djukovic, Costume Designer Sammy Sheldon Differ, and Music Supervisor Lindsay Fellows who discussed the development process with screenwriter Graham Moore, the challenge of bringing Turing’s story to the screen, the decision to have Tyldum direct, the vision he brought, what drew the designers to the project, how their research helped them design a period piece with historical accuracy, the actors’ input into their costumes, the musical choices, composer Alexandre Desplat’s score, their commitment to honoring Turing’s legacy, and his family’s positive reaction. Check out our interview after the jump.

Question: For the producers, Alan Turing’s story is so fascinating. How did Graham Moore’s script find its way to you? Was it difficult to bring to the big screen?

TEDDY SCHWARZMAN: The script came to me after about a year of development that Nora and Ido had been doing with Graham.

IDO OSTROWKY: We’ll start at the beginning just before we found Graham. It began in the fall of 2009 when we saw an article in which then Prime Minister Gordon Brown apologized on behalf of the government for the treatment of Alan Turing during and in the aftermath of World War II. Our first reaction to the story was that we were surprised that we didn’t know who Alan Turing was, and neither of us recalled learning about him in school. So we just began to research his story and thought it was profoundly moving and felt that it deserved to be told and for people to know who he was and what he contributed to the war. From there, we had to find some material to option, which is where Nora comes in.

NORA GROSSMAN: I went to London and I met with a biographer, and Ido and I were able to option the rights to Turin’s biography for very little money. I came back to the States, and we had a very big book and not many feature contacts and didn’t know many writers. But I had met Graham on the staffing meeting when I was working in television. I had a party at my house, and I was doing the song and dance of “I’m in between jobs, but don’t worry about me. I optioned this book. I have another project.” Graham overheard me talking about it and said, “Oh my Gosh, I’m obsessed with Alan Turing. One day when I’m a famous writer, that’s my passion project and I’d love to write it.” I said to him, “Hold on one second. Let me call Ido.” I called Ido and I said, “I think we’ve found someone to do this.” Graham was so passionate about turning the story that he specced it for us for over a year. We went through a few drafts and then were fortunate enough to have people read it and get excited about it and find Teddy.

SCHWARZMAN: I had first read it when it went out as a pseudo-spec in the fall of 2011 and had raised my hand very vehemently and said, “I would love to be a part of this movie.” But it ended up at studios and had a brief year there before becoming available once again. In the fall of 2012, I finally got to meet the illustrious Nora and Ido and Graham Moore who at the time were just these mythical figures. There was no shortage of people who wanted to partner with you on the screenplay, because as everyone knows, it was a Black List script and had been very well received. But I think the real question was how were we going to put it together, and what creative choices were we going to make, and how were we going to find a way to respect and honor Alan Turing’s legacy and make it in a way where every decision was being made in the best interests of that story. We were lucky enough from a practical standpoint to have a story and to have a script that in and of itself would be the hook in a weird way. So, we didn’t have to think about trying to cast the biggest names. We didn’t try and think about the foreign value of the film. We just thought about who cares and who feels the need to make this film like it’s not a job but it’s a passion. We were lucky enough along the way for everybody involved – from Maria, to Sammy, to Lindsey, to our director Morten, to our cast – where people understood the importance of this story and wanted to be a part of it to honor Turing’s legacy.

Can you talk about the decision to have Morten direct? I have to imagine this was a really hot script. You probably had your choice of directors.

SCHWARZMAN: We set out as three American producers and an American writer to find a British director. That really seemed to make a lot of sense to us. We knew that we were going to be shooting the film in the U.K. We knew we were going to be casting with an all-British cast. It felt appropriate to have a British director. But it just happened that this crazy Norwegian read this screenplay and fell in love with it. We had been asked by Morten’s agents to watch Headhunters and to have a Skype with him. We had agreed just out of courtesy not knowing who Morten Tyldum was. I don’t mean that rudely, but we had a very long list of directors and Morten was never on it because Headhunters had yet to come out in the States. He had not been BAFTA nominated as Best Foreign Film, and it was just a film to watch along with all the other research that we were doing. We watched it and we were blown away by the pure talent of the direction and a balance of different tones from the tension to the drama to the comedy, and then just the pure filmmaking and shot selection and cinematography.

It was a very, very difficult feat to achieve what was achieved in Headhunters. So, the question for us then became, “Okay, this person who we don’t know clearly has the talent to direct something like The Imitation Game with the various tones that were in this film, but does he understand the story? Does he understand what’s driving it and its emotional core? Does he know who Alan Turing is? If he doesn’t, does he understand or want to learn the historical significance and really invest himself. We met him. We Skyped with him right after watching his film, and within 48 hours he was our director, because everything that he said about what he wanted to do with the film was exactly what we wanted to do. I think he also wanted to make sure that this was a story that both told the triumphs but didn’t shy away from the injustice, while at the same time trying to make a film that didn’t feel like a traditional biopic that would take you beat by beat by beat through the story. It was probably the luckiest decision that we made.

For the designers, what drew you to this project? Obviously, the script is great.

MARIA DJUKOVIC: For me, it’s always the script. The script is the starting point. I was caught by this immediately. It was quite extraordinary how much impact that very first reading had. I immediately start picturing things from that very first reading. And then, when I was asked to do a Skype with Morten, which I was thrilled to do, we instantly got on in that Skype. He actually offered me the job in that Skype. And as a designer, you think, “Great. This guy’s decisive. He’s going to make my job a lot easier.” Also, if somebody takes three weeks to make that decision, it goes off the boil, but it was just instant (to Sammy) like your Skype with Morten. It was the same thing. And then, I met these guys (referring to the producers) in London and we were off.

LINDSAY FELLOWS: I was going to say I got brought in later in post. But the first meeting that we had, and what struck me walking into the room with Teddy and Morten and Billy, was he just sensed the importance of the movie right from the [beginning]. I screened it and I was just dumfounded that it was so together at a rough cut essentially with no visual effects, no anything, and the way Morten was able to keep the pacing going. When I went in for the first meeting, I was like, “Okay, these people really take this seriously.” I mean, every film is serious, but this one seemed to have a different level of respect for the material and the story. Everybody was really throwing themselves into it.

What were the challenges of designing a period piece? Obviously you’re tied to historical accuracy, but how much were you allowed to bring your own vision?

DJUKOVIC: I do a ton of research. These guys know. I literally have the art department wallpapered floor to ceiling with references and research, which I want to know. I want to be informed. And then, I don’t feel you have to adhere to absolutely everything, but it’s a very good starting point. The historical research as a designer, I think, should be part of our DNA. That’s so fundamental. That’s not what designing a film is about. That’s just there underneath and has to be there underneath. I’m often surprised. That whole thing of getting the period right is very, very fundamental. What you’re actually doing though as a designer has so much to do with conveying character, conveying mood, conveying an overall aesthetic for the whole picture. That’s the business of designing actually. We’re very used to seeing films which are set in Britain during World War II. I think it’s fair to say there’s a slight sameness to the look of a lot of those movies. Morten and I both wanted to give this film very much its own character and something that just made it feel a little bit different. But all that stuff is based on very, very, very through groundwork and research.

It pops in a way.

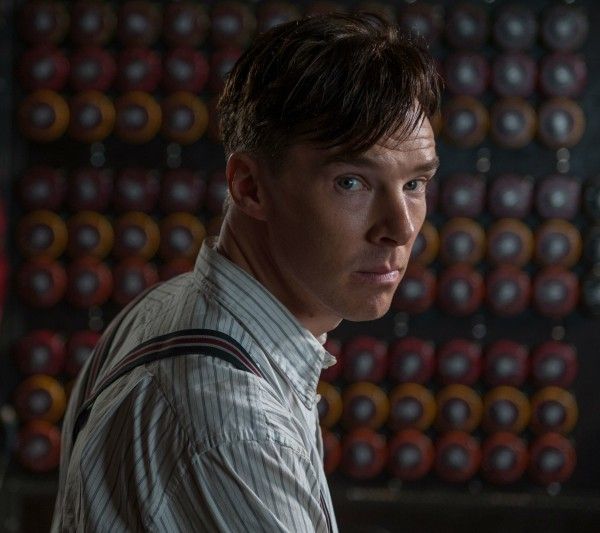

DJUKOVIC: The red. There’s a lot of bright color. Again, that’s not something that I imposed onto it. That’s something that actually comes from the research again. For example, the Bombe, Christopher, there’s a facsimile at Bletchley Park, and it has red wires coming out of it. I didn’t make that bit up. It does have red wires. I certainly accentuated it and blew them out of proportion slightly, but they’re there. It’s the same with a lot of Alan Turing’s own diagrams and sketches and schematics. That use of red is in them. I find that when you put the references on the wall, the mood or the color palette jumps out at you rather than us imposing it on it.

SAMM SHELDON DIFFER: We worked in a similar way with research from the historical and the real people character point of view. That has to be done first and then it takes on its own life. Obviously, we were working very closely with Maria using those colors to enhance. The red was really important, and we tried to place that in key areas.

DJUKOVIC: Neither of us was afraid of color at all.

DIFFER: No. I love color and I love it in big blocks. I wanted to be very faithful to the characters and also pull out key things that enhanced the mood. So, you don’t just be historically correct. You need to let the script give you the life of where it wants to go. It’s kind of a balance.

The authenticity of the costumes that the characters wore was impressive. What were some of the difficulties of the costuming?

DIFFER: We had a short prep time for this film. For me personally, I think it was five or six weeks. The film was set over quite a period of time. We only had so much to spend. I decided the best way to do it would be to see if I could find original pieces that we could either copy or use depending on whether they’re fitted. I found an awful lot of the original coupon clothing from 1940, which has got a CC41 label in it, which means it’s totally original. The vast majority of the principals have quite a few of the original pieces in there. I looked at photographs of the real people, and then tried to merge what we found and what we could make into their own little wardrobe, and then used the theory that people didn’t have a lot of clothing so we needed to be clever with how we changed to show time. Also, I wanted to bring in this color in a subliminal way, too. So, there were a lot of difficult things to bring together.

It all started with Alan, and then once we got Alan set, and we found the right store for it. There was one thing that I was particular about making which was the checked shirt that’s in all the posters. I searched forever to find that fabric to match a photograph that we had of Alan Turing. That became the center of everything we had. That very first outfit when he goes to Bletchley was a key thing. With a lot of the clothing, I didn’t want it to be neat. I wanted them to wear them, so they hung out in them, so it wasn’t crisp or anything, because people didn’t have a lot of clothing then and it was always made of natural fibers. England is damp so everything gets wrinkly. I wanted to bring all those things in so it felt like the Second World War, but at the same time give it an edge of just telling the right story. It was the same with Keira’s looks. With the research of Joan Clarke, there were only a few pictures I could find of her, so we used what we could and then we created from the script who we felt she was basically.

How much input, if any, did the actors have? I read somewhere that Benedict did so much research and would instantly know, “Yes, this is right. This is perfect.”

DIFFER: Yes. We tried a lot of stuff on him. I love being creative with the actor. I don’t just want to impose an outfit on them. I think the more they’re comfortable, and they feel it’s right for the character, the less you’ll notice it in a way. That means I’ve done my job. I think things that jump out as if it’s wearing them is not right. With Benedict, we did a lot of trying stuff on and how it felt when he was not just standing up but being Alan. It was the same with Keira Knightley. It’s a lot of going through the emotions of who they are. She was great.

Lindsay, I have to give you the biggest compliment, which is that the music in this movie really makes math exciting to me.

FELLOWS: Well, I’d like to take credit for that but Alexandre Desplat is just the best at getting in the head of the characters and really helping with the pacing. Honestly, the way the film played, just watching a dry cut of this movie was compelling. So, to have him continue to support that pacing of the film, there are moments where it almost feels like a thriller. To his credit, his themes really resonate. Whether it’s the war theme or the pacing or you’re in Alan’s head, it really stands out. He was under a very tight schedule to deliver that and he just killed it. He did a great job.

Finding music for a time period, is it more difficult or easier because there’s so much pre-existing than doing a film set in the modern day?

FELLOWS: Well, it depends on your budget obviously. Budget matters and we were on a limited budget with this, with a lot of the source music and the score for that matter. But we were able to get really creative. They were really picky about the choices we made for the bar scenes and things like that. We spent a lot of time trying to get them as authentic to the period as possible, but also not have super familiar songs that would take you out of the dialogue. And so, we felt like we were there. We were in the time period, but they weren’t necessarily the big Glenn Miller hit that everybody knows and that’s going to make you think about that. So, I think we nailed it on that end.

How historically accurate did you try to make the film? Wasn’t there a Polish team of cryptographers who had initially broken this code, and then Turing went to them and Bletchley took it over?

SCHWARZMAN: Well, actually the Poles didn’t break the Enigma code. They developed the first version of the Bombe, which they called the Bomba. Even our Bombe had to evolve over time as the rotors changed, as the plugboard got more developed, as it became harder and harder to crack the code. And there were different codes that were being used within World War II by different divisions. But we tried to give a nod to the Poles, because it was not as if the Brits and Bletchley Park adapted the technology to know how to break the Enigma Code. They did not. But at the same time, they had a starting point which ultimately they had to go back to from scratch.

From a philosophical standpoint, they had an idea of what they could possibly do, but they didn’t have a machine that they could implement. I think you’ll remember there’s a scene where Turing comes out to Commander Denniston and says, “I need $100,000 for the parts equipment.” It’s inspired by an old Polish machine, except this one is infinitely more advanced, which is a nod to the Bomba. And even the fact that the information that the Brits received initially came from the Poles is referenced when Commander Denniston first introduces the Enigma machine on the table and says, “Polish intelligence smuggled it out of Berlin, which is how we’ve now received it.” So, we tried to give a nod while at the same time make sure we weren’t underselling what actually was achieved at Bletchley.

And then the rest of it is biography and all the other elements were based on the actual events?

SCHWARZMAN: Yes, it’s all based on actual events. There’s certainly some creative liberty that’s taken in the interest of telling a movie, but just going at random is never really a good thing. Joan Clarke and Alan did have an incredibly close relationship. They did get engaged, and it was broken after six months, although they remained the best of friends. Turing proposed in the hopes that he could adopt some level of social conformity that ultimately became too difficult for him. They used to change their work schedules so that they could work side by side, and they would play chess together, and they would go on bike rides together. Even after the break up, they remained lifelong close friends. The scene where we meet Joan Clarke, when she arrives for the code breaking, that was how they actually recruited people to join Bletchley. They put a crossword into the Daily Telegraph which we’ve now just reissued this weekend as the film is opening in the U.K. So you can see the original crossword that was done.

There was a letter to Churchill seeking greater resources. It was actually written by both Hut 8 and Hut 6, but they weren’t able to get the resources they needed. From an engineering standpoint, it was partially on a human level. Everything that’s in the film is there for a reason, and we haven’t tried to create anything outside of what was necessary for purely dramatic where we take something like the Bombe and we call it Christopher. Christopher in Alan’s story and the time at Sherborne School is completely true. In the 1950’s, there was an investigation into Alan Turing. There was a robbery at his house. He reported it to Manchester police, and instead of following up on that robbery, they realized that he was gay, which then led to that investigation, which then led to his prosecution. But the interrogation scene and the confession didn’t happen. Because of the Official Secrets Act, Turing wasn’t allowed to tell anybody what he did and went to his death with nobody in the world knowing what he had accomplished at Bletchley Park, which is actually I think more powerful than what we were able to represent in the film, but we had to tell you.

Was the spy real, and if he went to his death without speaking about it, how do we know?

SCHWARZMAN: The spy at Westfield, John Cairncross, is actually very well known in the U.K. for having been at Bletchley and having spied for Stalin. Yet, MI6 was aware and fed him the type of information that they wanted to feed in order to get those messages. Cairncross thought that nobody knew and that he was pulling a fast one on everybody. He worked at Hut 6 which was right next to Hut 8. As you saw from the letter to Churchill, they worked hand in hand. I think one was U-Boat and one was Air Force. So, they were working on slightly different versions of Enigma, but working side by side. He and Turing knew each other very well, but it wasn’t him in the room. That part is a slight creative liberty. We know based on the fact that not all documents were actually destroyed.

When Alan Turing was pardoned, did this story come out?

OSTROWSKY: Well, I think the story has been gradually coming out over a long period of time. That’s how there’s a biography on him that we optioned. It’s because there was some information about his life. And just to jump back to the spy question, I think the salient point about the fact that it’s true is that there were no repercussions for Cairncross for what he did, and yet we contrast that with Alan Turing, and we see the way that he was treated when he obviously did nothing wrong. I think that’s really one of the messages of the movie, the injustice that he faced and how upset we still are about it and should still be.

When you read the book, you must have had the great vision to see that it could be cinematic. How did that happen?

OSTROWSKY: A lot of credit goes to Morten Tyldum for finding a way to open up the story. Obviously, you’re right, when you read the book and you see a lot of mathematical theory, it’s hard to figure out how that will become visual. For me, I want to add to one other location. We were fortunate enough to shoot at Sherborne, which is where Alan Turing actually went to school and where he and Christopher had their relationship. For me, that was the most profoundly moving location of the entire shoot, because I thought about how alone Alan must have felt at that time in his life and that there was such grand poetry to this idea that years later we were shooting right there honoring him at a time where he was obviously devastated by the death of his first true love. That meant a lot to all of us I think.

For each of you, what ended up being the most difficult aspect of working on the film? Was there something that you struggled with the most?

DJUKOVIC: We always feel there’s never quite enough time or money and that’s always the case.

FELLOWS: I agree. Usually you either have time or money or hopefully a combination of both. We were in the same situation, and I think that again it sounds silly, but you can just tell this film turned out. It’s so hard to get a movie to turn out at a rough cut and go, “Wow! We’ve really got to finish this now. This has got to be great.” We had to do everything we could do with the limited resources we had. That’s how we were able to get so many talented people to come on board and support the film in post, and during music, and with a very accelerated schedule for delivery. Everybody just rallied together. It’s always tough, but this was one where the effort was worth the project. You really felt good about it and you wanted to do your best work.

SCHWARZMAN: There was such a great responsibility on all of us, and I don’t say that in a canned way. There was such pressure that I think we all felt from day one of coming together, and you guys probably even beforehand, of not screwing this up, of telling this in a way that did justice. This was a real man, and these were real events that happened, and obviously there’s going to be some cinematic license taken. This was an independent film that was not intended to Hollywoodize the moment. I think that the question was always, “Would we be able to do this justice?” We were lucky. We screened the film for the Turing family. We were lucky enough to connect on the ground during pre-production with both Turing’s nephew and three nieces. Benedict was able to meet with some of the nieces and get first-hand accounts of Turing from a performance and a characteristic standpoint. One of them came to set and did a beautiful drawing while we were there of watching Benedict play Alan Turing. But you never knew if we would make this movie which will always have a life of its own, and then show it to them and they would be aghast. We were lucky to screen it for 26 of them and receive universal acceptance and appreciation. The eldest niece, who was 18 when Alan Turing passed away, said it was as she remembered and that we’ve done the family’s legacy proud. That’s a weight that we really all were feeling this entire time. So, to be able to do that and have them be such great supporters of the film is really an honor.