The Criterion Collection has issued both The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou and Red River recently, and though the two would seemingly have little in common, it turns out there are a number of parallels. Both films begin with the main character losing someone close to them in a way that drives the narrative, both follow a driven and arrogant man who needs to see the error of his ways, both deal with great adventure, both deal with a father/son relationship, and both conclude with the main character coming face to face with their supposed enemy, only to realize violence may not be the answer. Bill Murray and Owen Wilson star in the Aquatic for Wes Anderson, while John Wayne and Montgomery Clift star in Red River for Howard Hawks. My review of both The Life Aquatic on Blu-ray and Red River follows after the jump.

The Life Aquatic starts with Steve Zissou (Murray) showing his latest film where his partner Esteban (Seymour Cassel) was eaten by a tiger shark. With no record of the animal, people think Zissou might be crazy, but he suggests his next film will be about his finding and killing that shark. That’s harder to finance, and so the project stumbles. His wife (Angelica Huston) is pretty much done with him, but hope comes in the form of Ned Plimpton (Wilson), whose mother died recently and who may or may not be the son of Steve. But perhaps more importantly, he has an inheritance.

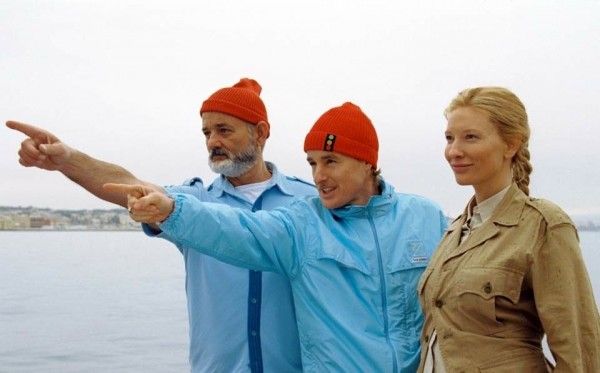

We get to meet Zissou’s documentary crew, which includes Klaus Daimler (Willem Dafoe), Vladimir Wolodarsky (Noah Taylor), and Pelé dos Santos (Seu George), who constantly sings David Bowie – albeit in Portuguese. New to the group is Jane Winslett-Richardson (Cate Blanchett), a reporter who wants to write a cover story on Steve. Zissou takes up Ned when he offers up his inheritance, and so the mission is on, though they have to take a bond company stooge (Bud Court) with them. But to find the tiger shark, they will need to steal equipment from Alistair Hennessey (Jeff Goldblum), Zissou’s nemesis.

I first saw The Life Aquatic when it was released in the theater in 2004 and the Criterion Blu-ray edition is the first time I’ve revisited since it came out. There’s a reason for that: At the time I thought it was Anderson’s worst film, on top of actively disliking it. On top of finding Anderson’s techniques more mechanical than organic as I had with his earlier work, I couldn’t get past the fact that the film sacrifices two characters so Zissou can learn a lesson about him himself. Anderson’s films to this point focused on narcissistic sociopaths, but previously I found them charming rapscallions, where Zissou struck me as just a terrible human being. Did ten years change my opinion? Or did his subsequent films?

I must admit that it’s not as bad as I once thought, and there are many things I like about the movie now. Perhaps I overreacted to the third act death of a character (even if it is telegraphed and meretricious) as on second viewing it becomes more about the randomness of life than punishment, even if the character is written as saintly. All my quibbles would be minor if the film didn’t feel a little unfocused.

Looking back on Anderson’s career, it appears that Aquatic is part of a transition period, which make The Royal Tennenbaums and The Darjeeling Limited a loose trilogy in this sense. Father issues have been a part of Anderson’s work since Mr. Henry in Bottle Rocket, but it came to the forefront in these three films, with Limited suggesting that it was baggage that needed to be let go. Aquatic may also be Anderson’s film that is most directly about the filmmaking process and the family that rises up from such an endeavor. But it’s also his most slack film, which may be why it’s his longest movie.

The cast is stacked with great talents, but they don’t have as much to do and are often limited to a character beat that distracts from the whole. Dafoe suffers most from this: he wants to be seen as a son to Zissou, and then that gets resolved a little too neatly. And while Bill Murray has become one of Anderson’s most reliable collaborators, his Zissou is his least interesting character in the Anderson oeuvre. A pot smoking dreamer, he doesn’t have the intensity that his mission would suggest, and (like John Wayne’s character in Red River, which I’ll get to shortly) the film has no interest in turning him into Ahab. That’s problematic as when a film’s main character isn’t driven by the film’s narrative, it takes a lot of gas out of the proceedings.

But, that all said, there are so many pleasures to get out of the film. If Anderson seems at his most Anderson-y here (the bifurcated submarine, which is a bit that may have been stolen from Tashlin or Tati or Godard or all three, is – despite the homage – so very Anderson), but the music and the sense of humor add much to the proceedings. Perhaps now that I’ve warmed to the picture I might revisit it more and it could grow on me with each passing viewing, and Bud Cort damn near steals the movie. It could grow, but if push came to shove, I’d throw on The Darjeeling Limited before it.

The Criterion Blu-ray ports all the supplements over from the previous release, while the film is presented in a perfect widescreen (2.35:1) transfer with DTS-MA 5.1 audio. Considering the precision of Anderson’s imagery, the Blu-ray is the best possible presentation of the material, and details pop in this new transfer. The film is accompanied by a commentary by Anderson and co-screenwriter Noah Baumbach, which was recorded in a café. This is as obnoxious as it sounds, though both are open about their process.

The film also comes with a documentary “This is an Adventure” (51 min.) by Albert Maysles, Antonio Ferrera and Matthew Prinzing that was done especially for the Criterion release. It’s a fly on the wall look at the film’s production. There’s no talking heads discussions, it’s just a look at moments from the pre-production and the shooting of the film, and for that it’s great. There are nine deleted scenes (5 min.) that amount to snippets cut from the movie. “Mondo Monda” (16 min.) is an interview with Anderson and Baumbach that’s done as if it were conducted on an Italian movie television show form the 1980s. It’s a little too cute for its own good. There are also cast and crew interviews (36 min.), though this is done in a playful Anderson style, and it’s followed by an interview with Mark Mothersbaugh (19 min.).

As shot for the film, Seu George played ten David Bowie songs (40 min.) and you can see those takes uninterrupted, while Matthew Gray Gubler made a behind the scenes video journal about his time acting in the film, and his character, Intern #1 (15 min.). Also included are photos and a design gallery, a more standard making of featurette (15 min.) and the film’s theatrical trailer.

Howard Hawks’ Red River is a defining work, but it also feels like a transition point. By the time Hawks made the film (the film was released in 1948, but was delayed) he had been working in pictures for over twenty years, and had mastered working within formula. He has also created some of the greatest motion pictures of all time with films like To Have and Have Not, Only Angels Have Wings, Scarface, The Big Sleep, His Girl Friday and Bringing Up Baby. The man had played in most genres, so it’s interesting that it took him until Red River to make his first western –- a genre the man is now closely associated with because of this and his three other westerns with John Wayne. Red River was also his first film with Wayne, who became one of Hawks’ best collaborators later in their careers. Hawks loved making fun pictures about people who liked their jobs, and after this only The Land of the Pharaohs -- which is one of the least interesting films Hawks made in the later stretch of his career – doesn’t seem to revel in its surroundings.

Here Wayne plays Thomas Dunson, who is moving out west with friend Nadine Groot (Walter Brennan) to raise cattle. He departs from a wagon train and leaves behind Fen (Coleen Gray), the woman he loves, and shortly thereafter her group is attacked by Indians. The only survivor is Matt Garth, who got away with a bull. Dunson takes Matt in and raises him as a son. But by the time Matt (played as an adult by Montgomery Clift) is an adult, Dunson is nearly broke and needs to move his thousands of cattle back East to sell them. And so they must go on a cattle drive.

So he gathers up his men, which includes new hire/gunslinger dandy Cherry Valance (John Ireland) and begins the arduous process of a cattle drive, which involves making fifteen miles a day if they’re lucky, fighting off Indians and coyotes, and keeping the men -- who get sick of eating beef and drinking bad coffee day in and day out – in line. If they don’t succeed it will destroy everything that Dunson’s built, and so he becomes more and more vicious as they proceed. This becomes more apparent when someone accidentally starts a stampede that kills someone, to which Thomas wants to whip the guilty party. This is seen as too much, which leads to Dunson getting into a gun fight with a couple of his men to stay in control. Matt sees that Dunson is driving the men to their breaking point and doesn’t understand why Dunson won’t go to Abilene with the cattle, though to be fair word of Abilene’s train station is a second hand rumor.

Eventually Matt reaches the tipping point and takes control over the cattle drive, which sends Dunson into a murderous rage. He’s left behind with no bullets or horse, but everyone knows that Dunson is coming and is plotting to kill Matt.

The ending of Red River is fascinating as it pits Dunson against Garth, and it’s as if Hawks couldn’t allow the natural ending to occur. He’s built up Dunson as a bullheaded man, and though we see that he’s starting to feel weakness about Matt when he meets the woman he loves (Joanne Dru), and can see the parallels to his own life, and that Matt was right about Abilene, he’s still a man of his word and comes to town to kill his son.

This gets into spoiler territory, but (to be fair) the film is over sixty years old. For the first two hours of the film Hawks has followed a familiar narrative: It’s very much of formula, but delightfully so. How the director shows the drive, and the effort that goes into it, the fracturing support and the need for mutiny is excellent. But Hawks, who was a master at invisible editing (the secret, he said, was to cut on action), couldn’t commit to what seems the inevitable conclusion as he decides not to kill either father or son. It’s shocking and almost wrong for the film. Except it’s the only ending that makes sense, because no one wants to see either character dead even if that’s what the film has been building to. In his classic works, Hawks has very little interest in villains or villainy. Really, only Scarface gives decent screen time to a bad guy. In his later works, the antagonists were usually rich jerks who are usually give a handful of scenes, while in something like Hatari! Hawks didn’t even bother to have a bad guy. But this seems to be Hawks concluding that he has no interest in tragedy, no interest in characters who can’t recognize good sense.

With spoiler discussion concluded, It’s worth noting that this was the first performance that gave Wayne a chance to show his range. Often called on for his imposing presence, he played a lot of cowboys and soldiers who were gruff but loveable. Here he gets to show that he could play an antihero. As legend says, this was the film that made John Ford say “I didn’t know the son of a bitch could act!” He’s well matched by Clift, who was just making his way in Hollywood (this would have been his first film if it wasn’t delayed). What’s interesting is that he has a lot of mannerisms (like touching his nose) that Ricky Nelson mimics in Rio Bravo. And there is definitely a through line to that film (Hawks’ next Western), most notably in the latter film’s use of composer Dimitri Tompkin’s score, which was repurposed into the song “My Rifle, My Pony and Me.” The narratives are not alike at all, but the attitudes are the same.

Rumor has it that Hawks started cutting down John Ireland’s role as Ireland when he found out Ireland was sleeping with Joanne Dru, who Hawks had an eye on. This seems likely as Cherry Valance is set up to do more than he does in the closing credits, and that, along with the film’s about-face ending could be called sloppy. But that doesn’t stop the film from being so entertaining and engaging, from being a master work. Like the killer in The Big Sleep that no one could supposedly keep track of, when you’re working at the level that Howard Hawks is in this movie, loose ends are meaningless. Red River is a great western, easily top ten material, and it’s great that Criterion has released the film.

The film is presented in a four disc set along with the book on which the film is based, Blazing Guns on the Chisholm Trail by Borden Chase. There are two DVDs and two Blu-rays included with identical content. On the first disc is the film’s theatrical cut (127 min.), which is the director’s preferred version, even though it’s been out of circulation for years as many considered the prerelease cut (133 min.) the director’s vision. The differences are minor: in the prerelease version there is text, where in the theatrical the film is narrated by Brennan’s Groot, while the ending – which Howard Hughes wanted changed because of similarities to his film The Outlaw (which Hawks started to direct before he was replaced by Hughes) – is slightly shorter. On first pass, I prefer the theatrical cut because it’s paced better, though Hawks preferred the longer ending on the extended cut. Both films are presented in their original aspect ratio (1.37:1) from new 2K restorations, with both featuring uncompressed monaural audio. These are gorgeous transfers, and the black and white photography by Russell Harlan is well preserved. The supplements are not extensive, but strong. On the first disc Peter Bogdanovich is interviewed about the movie (17 min.) and covers the basics, while the interview Bogdanovich conducted with Hawks (16 min.) is also included, along with a trailer for the film made for the film’s home video release.

Disc two offers the extended cut, while the supplements on that disc include interviews with film theorists Molly Haskell (16 min.) and Lee Clark Mitchell (13 min.) on the film. There’s also a 1969 interview with writer Borden Chase (10 min.) that focuses mainly on Red River, and the Lux Radio Theater adaptation from 1949 (59 min.), which featured Wayne, Dru and Brennan.