Hollywood New Wave director Robert Altman was on a winning streak in the 1970s. Every one of his films from the era had a major impact, each helping to redefine their respective genres during a period in Hollywood when everyone was questioning the traditional filmmaking formulas. From MASH’s bitterly cynical and darkly humorous take on the war film to McCabe and Mrs. Miller’s milestone revisionist approach to the western, it’s clear why Altman still stands tall among the many larger-than-life directors from this period. In the midst of this golden era came Altman’s 1973 take on classic film noir, The Long Goodbye. The film updates the noir genre for the hostile, idiosyncratic ‘70s, while developing an elegiac satire of the genre.

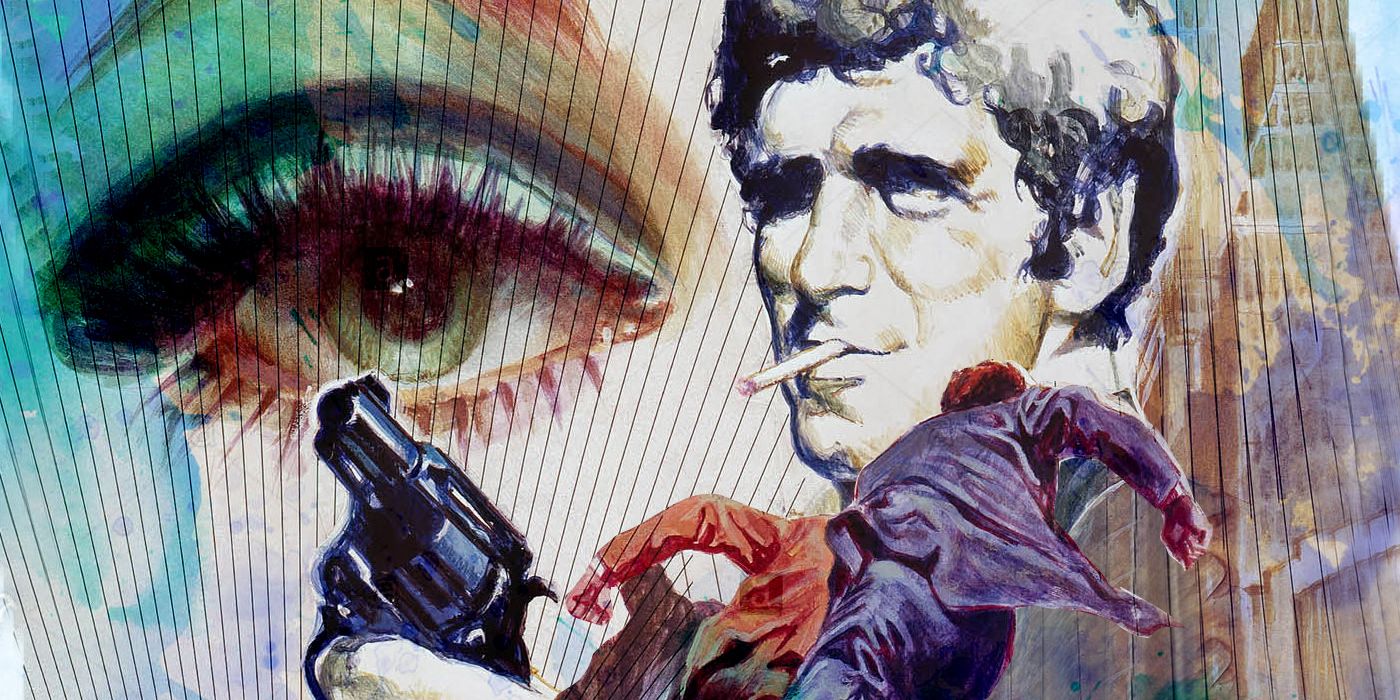

Adapted from the 1953 novel of the same name by father of hardboiled fiction Raymond Chandler, the film stars Elliott Gould as Chandler’s iconic private eye protagonist, Philip Marlowe. But it isn’t a conventional adaptation by any means. Altman famously said of the film’s many tonal and thematic deviations from its source: “Chandler fans will hate my guts. I don’t give a damn.” It’s not hard to see what he was talking about. In his film, Altman both eulogizes and ridicules the genre that Chandler helped create.

The film opens on a plaque memorializing the classic film industry, as showbiz anthem “Hooray for Hollywood” plays on the soundtrack. In a film about anything but show business, the viewer is instantly alerted of the film’s self-reflexive nature, with these elements serving to evoke the era of classic film noir that Altman is calling back to. The film’s extended opening sequence has detective Marlowe going out late one night to buy some food for his cat: a straightforward non-event, but one lingered on just long enough to call attention to itself. The sequence casually introduces the world of the film in seedy 1970s LA and its many bizarre characters, with a particular focus on Marlowe.

Marlowe is established not as the commanding, hardboiled tough that Chandler wrote about, but instead as an honest and caring man. When his neighbors ask him to pick up some brownie mix on the way out for cat food, he does so without expecting compensation. Though respectable, it’s a dependability quickly revealed to be easily exploited. As Marlowe returns with the cat food and brownie mix, an old friend is waiting for him at his house. Terry Lennox (former baseball player Jim Bouton) is desperate for a ride to Mexico. Marlowe drives him down, no questions asked. It is this act of kindness that will haunt Marlowe for the remainder of the film.

Altman’s utilization of side characters is another element that immediately stands out in this opening sequence. They are often far more fleshed-out than they really need to be for the sake of the plot, to quite an eccentric effect. Marlowe’s neighbors are young female hippies that always seem to be high and in a state of undress. The store clerk who helps with the cat food is a civil rights protester. There’s even a gate guard that does impressions. Throughout the film, minor characters of this sort add major color to the film’s LA setting, enhancing its realism. In granting all characters equal humanity, Altman gives noir something new. There’s a liberating sense that other goals and stories of equal importance exist outside of the protagonist’s limited plotline.

The main plot involves Marlowe’s strange journey following a disturbing revelation. Allegedly, Lennox killed his own wife before showing up at Marlowe’s place for the lift that night, and later committed suicide while in Mexico. Marlowe doesn’t buy it, and decides to investigate. Before he can get too far, he is swept up in a nightmarish series of encounters over which he has very little control. First he is arrested for possible connection with the murder. Then he is hired by Eileen Wade (an enigmatic Nina van Pallandt) to track down her abusive, alcoholic husband (a towering—and heavily bearded—Sterling Hayden), who may have been involved with Lennox’s wife. All the while psychopathic lunatic Marty Augustine (an unpredictable Mark Rydell) harasses Marlowe for money supposedly owed by Lennox.

One may think of Kafka when it comes to just how convoluted and absurd the plot can be, a playful exaggeration of the complex plotting in classic noirs. Everyone seems to owe someone else money. Lennox owes Augustine, Augustine owes the Wades, the Wades owe some shifty doctors. Marlowe is stranded in the middle of it all, and his principled sincerity is contrasted by their cruelty. Augustine enacts brutal violence on anyone he can to intimidate Marlowe. The Wades lie to and manipulate him. Even the police shove him around needlessly before arresting him. All Marlowe can do to cope is chainsmoke (a cigarette hangs loosely from his lips in every single scene) and tell constant wisecracks, which make a mockery of his dead-serious noir surroundings.

Cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond keeps frames enveloped in dark shadows, with intermittent and contrasting highlights, in typical noir fashion. But he fills the middle ground between these extremes with delicate, soft-hued color, achieved through exposing the negative to light in a technique known as flashing. This lends a dreamlike quality to the film, an impression that this is someone’s distant memory of LA noir. The camerawork is in a constant state of fluid motion, searching about in many zooms, pans, and tracking shots, just as Marlowe searches for answers regarding Lennox. The score by John Williams is just as fluid, with a single motif repeated in eclectic variations from scene to scene.

There’s a point in the film when the viewer realizes that Marlowe is, in director Altman’s own words, a “loser.” The private eye has already spent considerable time following a particular lead when it is revealed that, not only is he way off, the seemingly corrupt authorities are way ahead of him. The degrading sentiment is confirmed in the film’s closing passages, which imply that Marlowe’s very qualities of honesty and care are what have caused him so much trouble. One must lie, one must manipulate, one mustn’t have the upstanding morals of Marlowe if they want to succeed in the dark world of 1970s LA. Throughout the film, Marlowe drives an automobile from the ‘40s, importantly connecting him to the original era of noir. With Marlowe a stand-in for that age long gone, the disparity between his honesty and the dishonest world around him becomes a disparity between these two periods in time. The Long Goodbye of the title is not merely a reference to Lennox’s departure, but to the irretrievable, principled era of original noir.