When we list auteurs we often think of directors who possess a potent and identifiable cinematic language; you can identify their films by their color tones, camera movements and montage speeds. But there’s a subset of auteurs whose films feel so simple in their presentation that you aren’t aware of their composition. Iran’s Asghar Farhadi, the director of A Separation, The Past and About Elly, is such a director. He’s not identifiable by his camera pans and shot selection. Yet, even though his characters argue, present their points of view in closed quarters, move through rooms to let off steam, and then re-present their cases to the people who hold their fate in their hands—it would be too simple to call Farhadi merely a great writer. His auteur composition is in his editing; his pacing enhances the feeling that repressive societies create more fluidity in people; the restraint forces them to pace with their thoughts, take solitary breaks and let their surroundings reveal something illuminating.

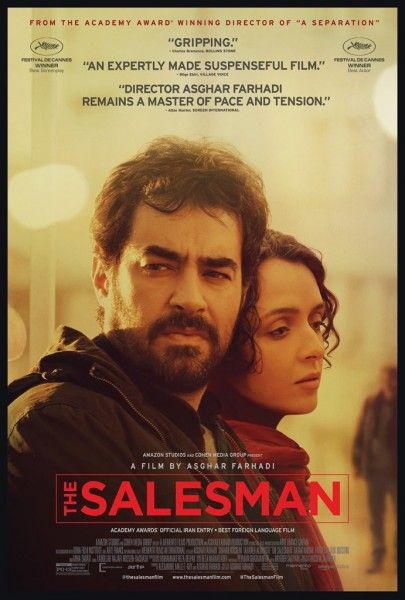

Although A Separation is still his finest work to date, his newest film, The Salesman, is a perfect example of why he is one of the best directors working today. On the surface, it feels very simple: a man seeks revenge against his wife’s attacker. But it’s his most complex work yet. And also his most risky. The result is a gripping tale that treads into darker areas than Farhadi has in the past.

The Salesman opens with lighting on a stage: there’s a neon liquor-store sign outside a window, a kitchen and a bed, but there are no walls. Farhadi then cuts to a building that’s being evacuated because the foundation is shifting due to the construction on the outside. This intriguing dual layer of the bare bones stage followed by a building that’s about to split its walls is a framework motif that Farhadi will use throughout The Salesman. The characters in his film put up many walls to hide their shame, but the characters that act on stage have no place to hide.

The titular salesman is actually Willy Loman in an Iranian adaptation of Arthur Miller’s famous play, Death of a Salesman. He’s played by Emad (Shahab Hosseini, terrific) a schoolteacher in Tehran who’s adored by his male students. His wife, Rana (Taraneh Alidoosti, heartbreaking), also acts in the play. They don’t appear to be serious actors, but rather a couple who’ve found something to share together. They lived in the evacuated apartment building of the opening and thus, are looking for a temporary residence. One of the other actors in the play (Babak Karimi) is also a cheap landlord and he just had an apartment open up and Emad and Rana take it.

A problem arises when the previous tenant refuses to come pick up her extra items in the spare room until she finds her next apartment. Emad and Rana, already irritated by being pushed out by their own building’s structural failure, push her items out onto the roof for a pickup that never comes. After the premiere performance of the play, Emad goes on an errand and Rana goes home to shower and prepare dinner. When she hears the bell’s buzzer she leaves the door open, thinking her husband is downstairs, instead it’s an unseen man who we learn beats her unconscious.

This is where The Salesman gets very interesting. Although there is certainly a dual read to be had with Farhadi’s use of Miller’s play—as Loman is one of the most tragic male figures of the 20th century, a martyr for the man’s burden to provide a life for an entire family—what’s most interesting in The Salesman is the multiple person-to-person failures in clarifying each escalating situation from moving the previous tenants items out to the attack.

First, Emad and Rana hear about how the woman who lived there before was a “little wild.” When Emad finds shoes, socks and keys to a truck in the living room and then money in the bedroom, he assumes that the previous tenant was a prostitute and his wife’s attacker was one of her clients. There is further evidence when he hears his co-star’s long ago voicemail on her answering machine she never picked up. But instead of asking his co-star, he lashes out at him. Similarly, his wife refuses to go to the police to report the attack, but her behavior—depression, and inability to be alone—hints that it was probably a rape or a vicious sexual assault, not just a beating. But she does not give any extra information and Emad begins to unravel because he doesn’t want to push her into revisiting the situation.

There is a turn that’s similar to Denis Villeneuve’s Prisoners, where Emad tracks down her attacker and locks him in an abandoned building, but The Salesman is not interested in torture or thrills. It’s interested in the torture of a human mind that can’t ask for the very information that will answer what to do next in these situations. How having questions but being prevented to ask due to cultural/societal norms can result in a being man locked up in a building awaiting a fate for something that only he knows he did and no one else. And in classic Farhadi auteur fashion, that fate involves many different viewpoints playing out in different corridors where only certain characters receive important information. For a movie whose plot is concerned with the structure of a building and the structure of a stage, The Salesman’s script is impeccably well structured. Like the main characters who are in the process of moving, there is a lot to unpack here.

There is a story structure to The Salesman that might upset Western audiences— particularly those who marched last weekend in the Women’s March and might venture to see the newest art house gem—because Emad doesn’t allow Rana to experience her grief how she hopes to and instead takes revenge into his own hands. Rana does not say what happens to her. She has stitches in her head and that’s all we know. As a viewer, we feel Emad's frustration because we follow him murkily on his path to revenge. The rape revenge film itself is a sub-genre in Iranian cinema, men achieving manhood by sticking up for their wives, but The Salesman is far more forward thinking. When you hear every character dance around assumptions of prostitution and sexual assault without ever actually getting close to saying either, there’s something very illuminating about Iranian culture there. If she was raped, she feels enough shame to not say. But that shame and the inability of her husband to ask (his own form of shame) is what escalates things. And therein lies Farhadi’s critique. How can we expect justice without being open about trauma and holding those accountable for inflicting that trauma?

On the surface, Emad and Rana are not as tragic as the salesman and his widow in Death of a Salesman. But carrying traumatic secrets and building up walls to contain them makes them very structurally unsound going forward. And eventually they too will crack. The addition of the play gives a nice “the show must go on” feel to The Salesman but life can’t really just go on in a society that constrains the ability to come forward without shame.

Grade: A-

The Salesman opens in limited release on Friday, January 27. It was also just nominated for Best Foreign Language Film at the Oscars.