When making a top 10 list for a year in cinema I like to think of the themes that seem to inform the year. Not that every film needs to fit a specific theme, but each year does seem to kind of speak to something in the time period in which it was released.

For 2016, that theme seems to be identity. Which is appropriate for the year itself. Identity politics is what people around the world are voting for or voting against; it’s individual groups of marginalized people vs. national flags blanketing populaces. The best films of 2016 chose to focus on how someone identifies himself or herself or how communities choose to identify them. Whether it’s by their religion, their sexuality, their victimhood or their shedding of victimization, their gender, their race, their artistry or their vocation, the concept of identity was massive in my favorite films of 2016.

It wasn’t just prevalent on my top 10 list. For films that almost made the cut, they too played with identity concepts. For examples from my runners up, there’s the required marital status of Kate Beckinsale and her daughter in Whit Stillman’s Love & Friendship or the Communist sympathizers in the Coen Brothers’ Hail, Caesar! The desire to be seen as more than a jock in Richard Linklater’s Everybody Wants Some!! versus the desire to be worshiped as a goddess in Anna Biller’s The Love Witch. And the attempts to maintain a familial legacy in Pablo Larrain’s Jackie or merge a family darkness with the family religion in Zach Clark’s Little Sister. Then there are the switching femme identities for power and subservience in Park Chan-wook’s The Handmaiden and Sophia Takal’s Always Shine. Then there’s a character who identifies as a private detective so in his bones that he discovers he’s a figment of the imagination of an author in Larrain’s Neruda; and finally for my runner ups, the identity of the very land being swapped from Mexico to the USA to the banks gets its due in David Mackenzie’s Hell or High Water.

Additionally, I cannot not mention a few films under this guise. Although I'm not as over the moon about Damien Chazelle's La La Land as most of my colleagues, I was totally enraptured by many moments and consider the audition-segue-into-the-epilogue section to be one of the most emotional moments of the year—and absolutely the best visual stretch ever done by a musical. And that film is all about saving the identity of jazz and fighting for your artistic identity against selling out. But it's Ezra Edelman’s O.J. Made in America, which chronicled O.J. Simpson’s decades of denial of his own racial identity to benefit his acceptance by corporate America which then warped into his acceptance of a black identity when he needed juror sympathy for a murder acquittal, that makes my year-end list difficult. Edelman’s mini-series was probably the best thing I’ve seen all year, but I did watch it on TV with commercial breaks and separate credits for each episode. Despite playing at Sundance in a full 7.5-hour format and receiving a brief theatrical run in New York and Los Angeles to become eligible for the Oscars, I cannot bring myself to include it on this list because I viewed at as a televised experience and can’t separate it from that. In that manner I’m identifying it as a mini-series. A monolithic mini-series that everyone should see. But in the debate on whether it’s a movie or not, I personally can’t label it as such. And I suppose I’m identifying myself by doing that.

It is not surprising that the narrative format of film largely favors individuals more than blanket groups, of course. However, in 2016 although identity politics is being roundly defeated around the world, it does seem worth noting that it’s still primarily the best way to focus a film: on the individual as they seek an identity. And that that’s what audiences want, even if the world is shifting its axis the opposite way. Nonetheless, here are my choices for the best individual stories of 2016.

10) Hacksaw Ridge

Let’s get a few things out of the way. Yes, Mel Gibson has immense anger issues and has said some deplorable things that I don’t agree with. But he’s certainly paid a price by not directing a film for a decade as he slowly worked his way back into Hollywood’s graces. He didn’t break an actual law, but an unspoken and blogged law of proper humane grace. I’d say he’s done the time (for now). And yes, his first film in a decade does feature immense violence in a movie about a medic who refuses to engage in violence due to his religion. But I don’t find that problematic either. In fact, it only heightens the surreal nature of the true story that Desmond Doss (Andrew Garfield) was able to save so many lives without ever pulling a defensive trigger while surrounded by one of the most chaotic and bloody battles of World War II.

As for the movie itself, Hacksaw Ridge is partly Archie Comics (the All American pursuit of the hot nurse in town by the gee-whiz local boy; the proud-of-his-body GI who’s forced to do his drills in the nude) and also one of the most harrowing war films ever made. There’s a commitment to wholesome cheesiness and a commitment to blood and guts and Gibson balances both handsomely. But what stitches Hacksaw Ridge together is the understanding that the most American thing to do is to fight for everyone’s code of beliefs and that we can also always learn something from each other. America is not meant to be homogenous in religion, personality or thought and allowing for conviction to individual codes—as long as no one is harmed by it—is what makes it great. Hacksaw Ridge is a faith-filled, bloody valentine to the necessity of strict dissension in Democratic nations. It’s goofy, it’s glorious and it’s heartfelt.

9) Paterson

Jim Jarmusch’s new film is certainly simple. It follows a bus driver (Adam Driver) in Paterson, New Jersey for one week. He’s named after the town he lives in and we follow him as he eavesdrops on passengers, purchases a harlequin guitar for his girlfriend (Golshifteh Farahani), visits his local pub on his nightly walk with his bulldog and as he writes poetry at the beginning and middle of his shift. Of course other things occur, but Paterson is powerful in its modesty and warm in the way it slows everything down to recite Paterson’s poetic works in progress.

With a perfect synergy from a meditative drone and the calm demeanor from Driver, Paterson is able to convey the very difficult task of an artist’s thought process as everything becomes still and elongated as he writes his thoughts on a pad of paper. It might not sound thrilling, but it’s a warm cup of tea and Jarmusch playfully dips the bag while stirring in tea. As a portrait of a relationship of would-be famous artists—he who follows a strict routine and she who changes her artistic pursuit on a whim—Jarmusch does not take a stance that one is better, just that simply doing is the best. The result is simply lovely and true.

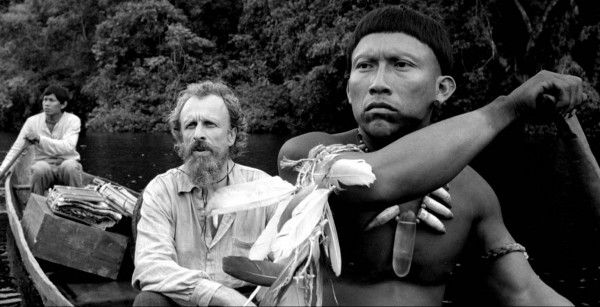

8) Embrace of the Serpent

Ciro Guerra’s Embrace of the Serpent follows two adventures taken by Karamakate, an Amazonian shaman played by Nilbio Torres and Antonio Bolivar, as he guides two different scientists in their pursuit of a healing plant 40-years apart. Shot in black-and-white there’s an anthropological excitement to his journey, but more importantly Guerra’s film is a guide about the long-lasting effects of colonialism and warped enforcement of morality.

This is a furious film that features many angry observations of how cultural and religious control reverberates over time until the very culture that colonialists attempted to suppress becomes something new and monstrous. There are many story parallels in Karamakate’s journey, but Guerra’s visual handling of the circular passage of time is stunning (one shot is particularly spectacular, as the two Karamakates pass through a river—separated by 40 years—still on a similar journey of aiding an outsider’s pursuit of a plant they wouldn’t even know by sight). There is a rage in Serpent, but it isn’t the only running current in the film. Thankfully, Guerra never loses the adventurous feeling that Karamakate is discovering something new about humanity and nature and that the blame for manipulating both isn’t a simple placement.

7) Arrival

A film like Arrival, which features a third act shift that completely changes many scenes you’d seen earlier, requires a second viewing to see if it holds up. Prior to seeing it a second time, what makes Arrival work is Denis Villeneuve’s withholding of standard thrills (in fact, when a coup happens, it happens almost entirely off screen) to focus on thrilling ideas, design and cinematography. What makes Arrival succeed even more—when watching it a second time—is Amy Adams’ deceptively deft performance.

On first viewing, Arrival is an exhilarating and cerebral sci-fi about language and how our world is not reaching its full potential due to our inability to communicate globally without misinterpreting threats due to how each society decodes language differently. But on second viewing, Adams’ quiet disillusion about images she’s receiving as a separate visual language provides a whole new interesting wrinkle to Villeneuve’s film. Surrounded by men at the site of an alien spaceship (as military strategists, scientists and grunts), Adams’ linguist is receiving messages that she must decode entirely on her own for fear of being dismissed for being too emotional. There is a lack of patience at the base—and at every base around the world—but there is no lack of patience in Adams’ performance and Villeneuve’s expert direction. I think you should see any movie twice to understand how you really feel about it, but Arrival is a requirement to see again.

6) Moonlight

Moonlight is a delicate film that could’ve easily been overwrought, following a young black Miami boy into manhood as he continues to struggle to form his sexual identity. Three different actors play Chiron in specific times of his life: as a child, as a teen, and as an adult (Alex Hibbert, Ashton Sanders, Trevante Rhodes). Each section of the triptych has a standout moment that speaks to the power understatement: two very different trips to the beach and a diner scene that washes us away.

Instead of having the big telegraphed scenes, Barry Jenkins favors secondary bits of dialogue to fill in the community’s narrative of funerals and prison sentences that are uttered like it’s just a natural progression. Instead of letting the great Mahershala Ali overtake the film with his beguiling presence as a neighborhood drug dealer who gives a safe space to Chiron, Jenkins lets us see the characters pain from his absence. And in the third act, Jenkins doesn’t give us an easy solution but instead we see two bodies that have carried the burden of self-denial for far too long.

5) The Witch

What a journey The Witch has been on. After debuting at Sundance almost two years ago it’s seen the world and lived deliciously long enough to land in the top 10 films of 2016. Robert Eggers’ confident puritan horror film has the gall to not only use proper period-specific English, but also regionally specific, with Carolinian prose for his Calvinist settlers. Although that language touch has turned off many horror fans, it’s but one of many great meticulous details that Eggers has imbued his gothic film with. The production design and clothing is impeccable. Never once does this film feel look like it was set in any time other than the 1600s. But that’s not reason enough to make a top 10. What makes The Witch great is that Eggers treats the isolated homesteaders’ fears as entirely real. Though his film pre-dates the Salem Witch Trials by about 60 years, many families truly believed that witches lived in the woods and terrorized them. And The Witch doesn’t attempt to trick us into whether or not a witch is terrorizing their family. A witch is. This commitment to reality adds the perfect layer to such a richly textured project and keeps the jump scares in check. Instead and more interestingly, Eggers is interested in achieving a moody awareness that these horrific things are indeed happening.

Eggers is aided by a gruff goat that’s the most terrifying villain of the year, Black Phillip, a booming-voiced patriarch, Ralph Ineson, a fabulously performed possession sequence from Harvey Scrimshaw and the find of the year in newcomer Anya Taylor-Joy as the daughter who loses the youngest child to the woman in the woods. The ending, which affords a woman a choice she would not otherwise have in that century, is perfection.

4) Silence

Silence has been Martin Scorsese’s passion project ever since he filmed The Last Temptation of Christ in 1988. It tells the story of three Jesuit priests in 17th century Japan. One (Liam Neeson) arrived at the height of Japan’s colonization and saw fellow priests and converted peasants tortured for not denouncing their Christian god. Eventually, he did denounce. Decades later, via a letter smuggled out by a Dutch trader, his students (Andrew Garfield and Adam Driver) venture to Japan to find him.

The mix of martyrdom and colonization is an immense conversation and Scorsese wisely decides to present both sides and eschew many emotional cues. Instead of utilizing a moving score, the soundtrack mostly enhances the sounds of nature, which is important to both the Christian god and the Buddhist pantheon, and puts the warring spiritualties on a similar plane of earthly existence. And the scenes of the Jesuits journeys by sea are filmed with a beautiful foggy immersion that heightens the ambiguity to the necessity of Garupe (Driver) and Rodrigues’ (Garfield) journey.

Ultimately, Silence is a patient film and it’s very much about how Rodrigues’ spiritual journey runs astride nations converging. Universal truths no longer exist in the convergence of cultures. There’s a sadness to that awareness, but faith does become much more personal. And Scorsese’s deeply personal film is one of the most profound movies of his career.

3) Sunset Song

The early 20th century Scottish countryside is filmed with an idyllic, painterly eye in Terence Davies’ newest film. The green hills roll, the wheat sways, the lake is a proper blue, and the horse hoofs to town take us to schoolhouses and kind town folk. It’s what life is meant to be. For Chris (Agyness Deyn), however, that idyllic light is repeatedly snuffed out in her homestead. First by her overbearing father (Peter Mullan), who repeatedly and dangerously impregnates her mother and beats his oldest son for the most minor of transgressions, and then by the words of community leaders who would brand her husband (Kevin Guthrie) a traitor and a coward if he does not enlist for War.

There are many breathtaking shots in Sunset Song (lensed by Winter’s Bone’s Michael McDonough), but there is a higher purpose here than mere painterly pictures. Quietly, Song is perhaps the most humane and feminist film of 2016. Chris’ home, particularly her stairwell, is filmed in vacancy or just with Chris, repeatedly throughout Song, the perfect rays of morning light spreading out the promises of a new day—a new day in which she routinely assists in running the family farm. The darkness in the film comes from the taking hand of her father and the idyllic community and husband that turns on her due to notions of what a man should properly do. It’s a man’s world, here, but Chris can routinely pause and see the light that they no longer can because of horrors they’ve been forced to witness. The men take too much burden upon themselves when women like Chris can surely aid in shouldering those burdens with strength, grace and light.

2) Toni Erdmann

"Toni Erdmann" is the alter ego of Winifred Conradi (Peter Simonischek). He has fake teeth, a wild wig, and says whatever might throw the conversation askew. For instance, he tells a man delivering a package to him that he loves ordering live bombs and defusing them before they go off, while wearing a beeping heart monitor. When Winifred goes to visit his workaholic daughter (Sandra Hüller) in Romania, “Toni Erdmann”, life coach/political cartoon comes to life and then appears throughout her daily schedule, rubbing elbows with elite investors in his grotesque get-up, mildly making a mockery of their elitism. It all leads to the most uncomfortable office party imaginable with naked bodies and a Bulgarian folk monster costume that’s eight feet of hair.

Maren Ade’s Toni Erdmann is a film that’s full of surprises and immense depth. Sure, it has screwball elements and a character that seems to be inspired by Andy Kaufman‘s confrontational alter egos, but there’s more than pranks to Erdmann—there’s some major theatricalism at play. First there is only one participant in the disruptive games, but—when Ines begins to embrace the macabre—there are two. Together the father-daughter relationship becomes a yin-and-yang duo of comedy and tragedy. And with Ade’s careful construction, Toni Erdmann‘s offsetting comedy and tragedy seeks to find some sort of balance in our current disruptive and disconcerting times. “Toni Erdmann” is a life coach, after all, and the lesson is that as our world becomes more and more tragic, we can never lose our sense of humor—or openness to something unexpected—due to rigid and empty pursuits.

1) Elle

Paul Verhoeven is always full of surprises, but Elle might be his biggest surprise. Even though the there’s a rape revenge genre pic right there for the taking, the deliciously subversive Verhoeven does something far more interesting and makes a character drama instead. Don’t be fooled by the American marketing, though Michele (Isabelle Huppert) wants to find the man who broke into her house and brutally raped her, Elle is primarily about how this interesting woman reacts to trauma on a very personal level. We slowly learn that Michele, who is a video game programmer, had a previous traumatic experience, which has numbed her in certain ways. Verhoeven peels the layers of an onion and Michele refuses to cry.

To be perfectly honest, although Verhoeven is one of my favorite directors I was admittedly a little wary about seeing him venture into a film whose central plot point is a rape, but Elle is so completely unexpected. There is humor, there is a delightfully close female friendship, there’s true crime TV, there’s an end line that sounds like Verhoeven is angry at the Catholic church for their sex crime cover ups; there are so many levels of trauma here that’s handled in a manner unlike you’ve ever seen before.

Of course, the whole thing hinges on Huppert’s performance and it’s the best she’s ever given. Which is saying a lot. Huppert doesn’t attempt to normalize Michele’s behavior—she makes it character specific. She doesn’t aim to shock with her cold and detached reaction to something so brutal—she builds a character that makes that response believable. Because she responds so much differently than we’d expect from a movie character (or even a friend in our own lives), it’s imperative that we believe that Michele would actually respond as she does. And we do. The result is not only the most surprising film in Verhoeven’s filmography, but it’s also one of his absolute bests.

More Recommendations

My honorable mentions (in alphabetical order): Always Shine (dir: Sophia Takal), Everybody Wants Some!! (dir: Richard Linklater), Fire at Sea (dir: Gianfranco Rossi), Hail, Caesar! (dir: Joel Coen and Ethan Coen), The Handmaiden (dir: Park Chan-wook), Hell or High Water (dir: David Mackenzie), Jackie (dir: Pablo Larrain), La La Land (dir: Damien Chazelle), Little Sister (dir: Zach Clark), Love & Friendship (dir: Whit Stillman), The Love Witch (dir: Anna Biller), Neruda (dir: Pablo Larrain), Peter and the Farm (dir: Tony Stone), The Shallows (dir: Jaume Collett-Serra) and Things to Come (dir: Mia Hansen-Love)

Special Mention: O.J.: Made in America (dir: Ezra Edelman)

Worst Film of the Year (tie): Collateral Beauty (dir: David Frankel) and Kill Your Friends (dir: Owen Harris)

For more of COLLIDER's Best of 2016 coverage, click here or on the links below.