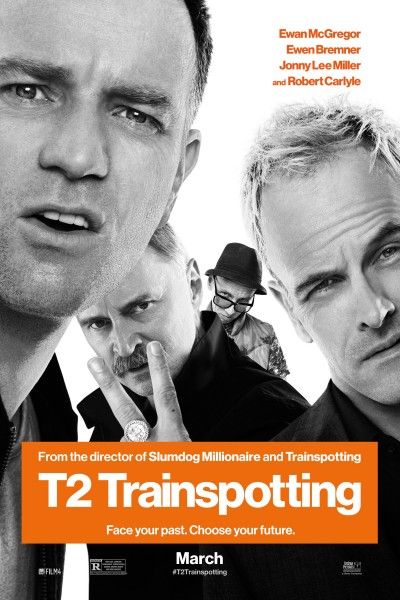

Last week, I had the pleasure of talking to director Danny Boyle about his new movie, T2 Trainspotting. For those who are unfamiliar with the upcoming sequel, it takes place twenty years after the original and follows Renton (Ewan McGregor), Spud (Ewen Bremner), Sick Boy (Jonny Lee Miller), and Begbie (Robert Carlyle) as they cope with how little their lives have changed over the past two decades. I really enjoyed the film, and you can click here to read my review.

During my conversation with Boyle, we talked about why the time was right to do a sequel, look back at his own life since he made the original, if it would be tougher today to make Trainspotting than it was in the mid-90s, the controversial release strategy that hurt Steve Jobs at the box office, his upcoming TV project Trust, how storytelling for TV differs than storytelling for film, and more.

Check out the full interview below. T2 Trainspotting opens in limited release on March 17th.

COLLIDER: So I wanted to start off by saying that part of this film’s strength is that a whole twenty years has passed since the original. Were you concerned about ever jumping into a sequel too soon?

DANNY BOYLE: It would appear so, wouldn’t it? It’s funny, actually. We tried, we did try. We didn’t try initially, which was when most people would do it, like, you know, a sequel normally arrives a year or two years after the original. There was never any talk about that after the first one, even though the first one had been very successful. But we did try with Irvine’s ten years later book, Porno. And we did adapt it, but we were very disappointed with it, I think, with what we’d done. And it felt like a very kind of obvious and traditional sequel. And even though it had some of the same ingredients as this one, you know, Renton returns to Amsterdam, Begbie’s been in jail, things like that, so it was only when we got together after—when the twenty year anniversary loomed on the horizon that we thought we’d better have a look at this and see if we think we can do it, or forget it for good. The stuff we were doing then became much more personal, surprisingly painful, actually, about us and about our age, and I think the actors then picked that up when they came in. And so it did become a more personal film than we were expecting, and that stops it being a sequel, because actually, its prime reason for being is actually in the emotion of the aging rather than in the necessary, the fact that it’s a sequel to the first one. It is, and obviously you build that within the film, it feels like a sequel to the first film, it refers to the first film, but the real reason for making it is what are these guys like now? What has time done to them, you know? And how poorly have they aged? And indeed, men do age very, very badly. That’s sort of what the film’s really about, I think, is how—certainly compared to women—how badly men age, how we just don’t want to and how we hang onto the past. So it became about those kind of things, really.

You know, there is a lot of reflection on the part of these characters about what they have and haven’t done. Coming back to the story, was there an element of reflection for you as well?

BOYLE: Oh god, yeah. Yeah, you can’t help but the actors, for instance have all become fathers since the original film. All four of them. They weren’t fathers when we made the first film, and they are fathers now, all four of them. [laughs] I’d had my kids by the time I made the first film, but yes, it does lead you to reflect on whether you are -- what sort of father are you? Which is obviously one of the things in the film. Renton wants to be a father and isn’t. Begbie’s a terrible father, which he realizes by the end of the movie, which is a slight moment of hope that some kind of atonement has been reached for him. And Sick Boy’s clearly a terrible father, he has nothing to do with his child, and Spud, also, his partner is protecting the child from the chaos that normally, he provokes around him. The hopelessness he provokes around him, as well. So yes, it does make you reflect on your own role, really, in that pattern of fatherhood, I suppose, yeah. The first film’s really, you could call boyhood and this is manhood, really. And so all the consequences of that manhood are what you look at, in terms of the characters and in terms of your own life as well.

You’ve been in this business for a long time now. Is it harder to get a film like Trainspotting made today than it was twenty years ago?

BOYLE: Oh god, yeah. I mean, not in terms of Trainspotting 2, but I think in terms of getting the original made would be more difficult now, wouldn’t you think?

Oh, yeah, absolutely.

BOYLE: That kind of risk-taking would be much more difficult now. The industry feels much less naive than it was back then. I think it was naivete that allowed us to make it, the original. Literally like, a kind of like, innocence, really, in a way. And it lacks, the industry seems to lack that at the moment, I think, you know. It’s probably been beaten out of it by the reality, the economic realities, I suppose. It’s interesting, it’s really sad, I think, because I think one of the things that’s extraordinary about, for me, about the film, and about movies, is that movies are time. There is no other art form that gets anywhere close to the way that movies can look at time. Because all you do, and you realize it when you’re in editing, especially on a film like this, is that movies, they compress time or they extend it. They slow it down, they speed it up, they stop it, and then they unlock it. And there’s no other art form that does that as acutely. And also, in the cinema, when people walk into the cinema, they give you -- and in fact, they pay for the privilege -- they give you two hours of their time. And they say, “Go on. I’m not going to do anything else for two hours.” There’s no other art form that does that, anything similar at all, it’s an extraordinary, wonderful kind of platform in which to discuss time, really, the passing of time. Which we all, which equalizes all of us, movie stars, peasants, the lot of us, the whole of us to the President are all the same. And it’s such a shame that there aren’t more risks taken with those opportunities in film, I think, you know?

Well, it can also all be so fleeting, because there are so many movies to see and they come and go and you think about them, but then in some ways you’re on to the next one. Looking back at your filmography, is there any project in particular that you sort of wish had received more attention, or that you think people should seek out and didn’t see it enough when it was in theaters?

BOYLE: I mean, the ones that don’t do so well, you’re always very caring of, you know? Because obviously the popular ones, everybody else kind of talks about or looks after, it’s the ones that didn’t do so well that you kind of like, try to care for in the afterlife or kind of like, you know, in the residential home of all movies. So yeah, there’s films like Sunshine and Millions, which I’m very, very proud of as movies, and they didn’t do so well, you know, and -- so yeah, you have that affection towards them. Whereas the ones that do very well pass from your ownership, you know, you’re no longer in charge of them, you know, people know more about them, especially like Trainspotting, people know more about the original than I do. So yeah, it’s [laughs] yeah, I think very affectionately about the ones that didn’t do so well.

I really enjoyed Steve Jobs and I was a bit bummed about how it was rolled out in the US.

BOYLE: Yeah!

Looking back at that film, what are your thoughts on how it was released?

BOYLE: Yeah, it was—I mean, it’s obvious, really, in retrospect. It’s easy, isn’t it? But it felt like we should’ve started smaller and grown more modestly. But if you go big early, then it has to work or there’s no way back for you. Yes, I did, I thought some of their work in that film, the actors’ work, was extraordinary, and it’s an extraordinary script, it’s so -- it takes so many risks with the biographic form in film, which I was very proud of, you know? So -- but yeah, you have to -- it’s a very complicated process, releasing a film, just like it’s a complicated process making them, and you can get it wrong just as easily as you can get it right. We’re all -- if everybody got it right all the time, everything would be perfect and it’d be a really boring world. [laughs] It would be, wouldn’t it? Think about it! It’d be terrible! Even though it’s painful, personally, at the time, you know?

Do you have any projects that you’re working on that you have coming up?

BOYLE: Yeah. We have a series that we’re developing for -- a television series that we’re developing for FX, which is a kind of like, five decade family thing. Which in theory, would happen over five years, each series would shoot every year for five years, and each series is about a different decade, and the first one would be set in the 70s and would happen in Italy and England, and we’re hoping to begin shooting that this summer, and it’s called Trust. So that’s our plan at the moment. So again, it’s interesting because it’s a very different form, long-form storytelling, and it’ll be very interesting to see how that affects the way one works and one behaves. The actors become the storytellers, really, you know, once you’ve set them up, it’s they that carry the burden of the storytelling, really. I’m really fascinated by that. So we’re working on that at the moment, the scripts are very good, by Simon Beaufoy, who wrote Slumdog Millionaire, and it’s the same producer as Slumdog, Christian Colson, as well, so it’s the team of us back together on that one.

What is it, do you think, about television that’s attracting you and so many other talented filmmakers? Because, you know, Steven Soderbergh has The Knick, the Coen Brothers are doing a TV series. What is it about that format that’s really sort of sparking to filmmakers these days?

BOYLE: It’s inspiring that you have the trust of risk-taking. Risk-taking in movies is so fragile because of economics. Whereas in television, because obviously there is, to a certain degree—and you can’t over-rely on this, obviously, it would be unhealthy to do so—but to a certain degree, there’s a captive audience who’ve already paid for the experience, and they want the reward for having paid, so you’re allowed -- the producing company, if you like, the television channel, wants risk-taking. And they’re happy to, within that, to acknowledge that not everything will be a success, but that’s not gonna let them inhibit some of the extremity of the storytelling that they’re prepared to make on. I think that’s the equation that makes it so exciting, I think, is that risk-taking is almost is more valuable in television at the moment than it is in movies, really. That’s how it seems at the moment.

As a storyteller, do you feel more pressure or more freedom that you have that audience? For a film, you only have to hold them for two hours, in a show, you have to hold them for eight or thirteen or what have you?

BOYLE: Yeah. Yeah, I mean, like I said to you, there’s something unique about movies that the audience literally gives you two hours of their time, but exclusively, so exclusively, there’s nothing quite like that. So I don’t think you’ll ever replicate that, but the extended storytelling idea that you’re asking them to develop their love of the character over a longer period of time where you can take risks with that character that may be not apparently coherent but will eventually reveal as being complex and complete is very interesting in television, I think. It’s like a Dickens novel compared to a short story, really, in a way. The breadth that you can spread across, I think that’s really interesting.

With Trust, do you hope to direct every episode or will you share directing duties with other filmmakers?

BOYLE: No, I will do the first two or three, we’re just deciding that at the moment. I’d love to do them all but I think that would be wrong, because I think the danger would be that you’re not allowing the form to take over. You’d be trying to do ten mini-films, which is not the form. The format is that you’re letting the characters tell the story, and directors are an aid to that rather than being the driving force. So I’m gonna limit it to two or three, really, we’re just in the process of deciding whether it should be two or three.

There’s so much diversity in your filmography, and when it comes to looking for new projects, is there anything that you look for in particular or do you just kind of take things on kind of a case by case basis?

BOYLE: It’s very instinctive. I’ve always believed in that. Because often, you believe in things and people who are more cool-headed say, “Oh, my goodness me, you don’t want to do that.” There’s also some reasons people can talk you into things, but I’ve always been very instinctive about it, that you read something or you discuss an idea and you just know it’s for you. It’s kind of difficult to explain rationally, necessarily, that’s not a bad thing. That can be the most interesting part of it, that you find out when you’re doing it why you’re interested in it, why your instinct was leading you to it. There’s risks, of course, because you can find it fell off, but actually most of the time it does bare through, you know, its richness develops because of that, I think. So I’ve always been very instinctive like that, rather than calculating.

When it comes to the world of Trainspotting, do you see yourself maybe coming back to these characters again in twenty years?

BOYLE: [laughs] I know we set ourselves up for that question, really. No, you do, you just do! I don’t know, I think that, it doesn’t seem plausible that anyone would be interested in watching then, but who knows if I’ll be watching things then. I think the main thing is rather than the neatness of the equation is that do you have anything personal to say about it, using them? Is there anything personal? Which there was this time, which made it a reason to do it, really. I think that’s the key thing I’ve learned. T2’s not that you’re immune to people’s reactions to it, but you are protected against that —you have something valuable that you want to share with people—which is the great instinct of storytelling, that you want this story to get out there not for commercial reasons, but for reasons that people will find interest in it about their own lives.

T2 Trainspotting is currently playing in limited release in the USA and will expanding March 24.