It's not every day I get to participate in an on-set interview with the CEO of a movie studio like Laika. It's even rarer that said CEO happens to be as experienced and passionate an animator as Travis Knight. You might think that being either the CEO or the producer/lead animator would be enough responsibility to fill your days with, and you're probably right, but Knight manages to balance his schedule between the two extremes. In fact, his executive duties help him keep Laika's big picture in mind, while the extremely detailed stop-motion animation work allows him to focus in on necessary minutiae.

Knight was in the middle of shooting a sequence when we visited him on set. He kindly took the time to talk about his experience as CEO and his plans for Laika's future, including the ambitious goal of producing a new feature every year. He effortlessly switched gears to walk us through the process of shooting scenes, which start way back in pre-production planning and involves quite a bit of organization before a puppet ever sets foot on stage. Knight is an instantly likable fellow, which not only comes across in this interview, but in his work on Laika's charmingly unique films. Hit the jump to see what he had to say, and be sure to check out The Boxtrolls when it opens on September 26th.

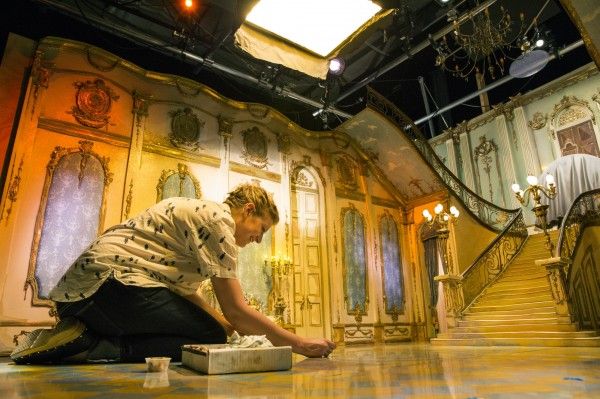

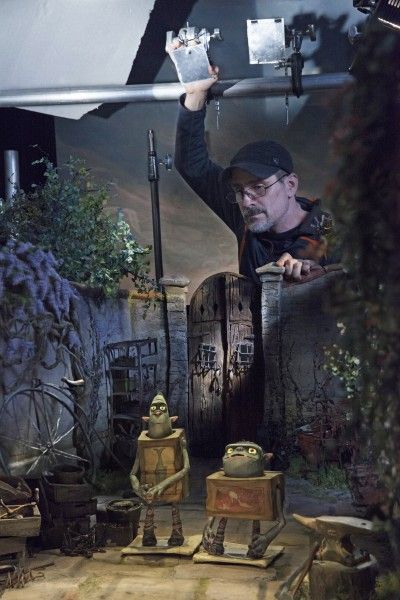

Travis Knight: [On Set] The top of the town, this is the Market Square, a portion of it anyway. These two guys here are two of our baddies, this is Mr. Trout and this is Mr. Pickles. One of the things you’ll notice is that Mr. Trout is held up by this rig here, and because of his design, he’s very top-heavy and he’s got these really spindly little legs, so he can’t really support his own weight. If I were to take the rig off, he would just flop over, he can’t hold himself up. And so what we’ll do is, I’ll shoot the shot with him moving around and the rig holding him up, and then I’ll shoot a plate afterwards, and then we paint that stuff out. We do that often for things that need to jump or run, things that need to be suspended in air some way or that need to be held up and can’t support their own weight. That’s a lot of what our rigging department does.

When we start a shot, we get an exposure sheet. This particular shot is really long; it’s about 1,100 frames, so I have about 15 or 16 of these pages. What it is, every shot is broken out phonetically by character. So this character, Pickles, right now he’s saying, “Universe, Mr. Trout.” So it’s broken down into every single frame phonetically what’s happening. And then that corresponds to a face in my face kit, which you can see right here. Hundreds of these faces that I can then swap out. This tells me on this frame here, 238, I need to grab this mouth here and I take that off and put it on. It’s held together by magnets. So, yeah, this is the way we do it. Just chip away at it one frame at a time.

How do you find time to do this and still be CEO of the company?

Knight: [laughs] It’s a balancing act. I ask myself that a lot. It’s a funny thing. I think when you look at some of the aspects defining this company, it’s that we are a community of artists, so it makes sense for an artist to be at the helm of the place. This is something I’ve been doing for a long time. Finding a way to transition between those roles is a challenge. Sometimes I’ll do it multiple times within the same day; I’ll go have some kind of a meeting and then I’ll run out here and shoot for a half an hour, and then go back out for something else, then come back in here for an hour. So, my days end up getting very scattered, my brain starts getting a little congested. But in a lot of ways, just being an animator for years prepared me for it in the sense that, when you’re working on a shot, you’re focusing on very granular detail, very fine detail, but you have to be able to extricate yourself from that and look at where that fits in with the overall shot, and where that shot fits in with the sequence in the film. You have to chart all those things in your head. So being able to bifurcate my brain over the years was a pretty good mental exercise for some of the things that I’m handling now. I have to go back and forth between some of the most granular detail and some of the big-picture stuff we’re doing as a company. So it can be a challenge at times, but I enjoy it.

Is being CEO sort of the price of being able to do this part?

Knight: It’s funny because I’ve found that each job has made me better at the other. One of the things about being an artist is that you can find yourself getting lost in detail and losing sight of the big picture. As a CEO, as an executive, I can’t do that, I have to think about the big picture all the time. So that’s an aspect of it that’s kind of trained my brain to keep everything in mind when I’m doing these things, to keep the right perspective. As an executive, it’s one of those things where you never want to lose sight of what it’s all about, what we do, which is create films, create stories, make art. Because I straddle both things I can never lose sight of that; I’ve got my hands in this stuff every day, so it’s actually, I feel like it made me better at this job.

Can you talk about the decision to adapt this particular project both from a CEO/producer’s perspective and from an artist’s perspective?

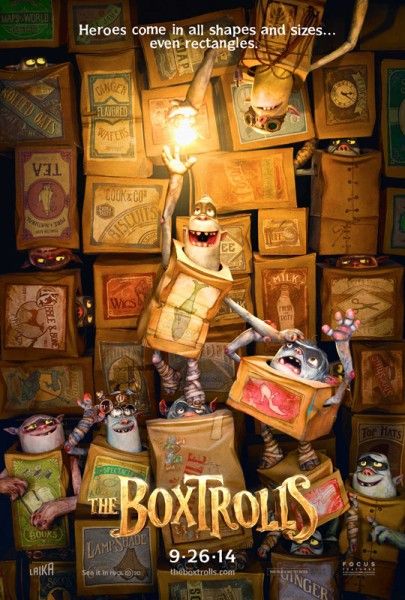

Knight: Yeah, “Here Be Monsters!”, which is the book this film is based on, was something we acquired almost 10 years ago, right when the company was first starting. It was basically two things: it was Coraline, and this thing, and we were just getting going. Alan Snow’s book reminded me of the kind of childhood stories I grew up with, things that I loved. Things like Roald Dahl and, more recently, J.K. Rowling. It was this whole dreamed-up universe with these fantastical characters and these weird settings and weird creatures, but he told this incredible story that was just rich with material that I felt if we could crack it, we could have something that was special, something that was unique and timeless. It took ten years to crack it [laughs], it took a good long while. It’s a big book. It’s got tons of characters, it’s over 500 pages long, and trying to distill that down to a 90-minute film, it’s an effort. You’ve got to find a clear film story within all that stuff. There’s enough material in that book for multiple films, but we had to really get down to what was the core of the story we’re trying to tell. And in the end, the film doesn’t resemble the book very much at all; there are core elements of the book that remain, but in initial drafts we were very, very faithful to the book, and we were not getting to the place we needed to be. We needed to kind of find the heart of it, emotionally, what was the heart of this story we were trying to tell. It came down to this, at the time, Tony [Stacchi], one of our directors who was leading some of the development on the project, he was based in LA but he was working up here. So he’s flying back and forth all the time, this incredible torturous commute, and he had a newborn son at the time. So he was struggling with those things that I think all of us as parents struggle with, which is trying to find that balance between family and meaningful work, and that’s kind of where it started to focus in. It became a story about family, it became a story about fathers and their children, and all the different permutations of that. That’s when we really nailed in that this is a story worth telling. Of course, you drape that all in this incredible world, and I think we have something that’s pretty special and visually stunning as well.

So from an artist’s perspective then, when you were in the process of adapting this, was there anything in particular you were looking forward to bringing to life, and anything that was daunting?

Knight: Well, yeah, I mean it’s all daunting. It’s a funny thing because stop-motion on both scales is really difficult to do. Kind of the big spectacle, the big action, the bigness of it all is really tricky because everything has to be built. On the other side of the equation, the really small nuanced stuff is really difficult to get out of these puppets. I’ve got these big meaty ham hands and I’ve got to somehow coax a subtle performance out of these characters. There are times when I’m literally tapping it just to get a tiny little increment of movement just to get the sense that the character’s shifting its weight. So that kind of subtlety, which is really what we try to put into these films, is incredibly difficult in this medium.

I thought that this particular story with this world, it was really ripe for some visual innovation. When you look at what we’ve done from film to film, with Coraline to ParaNorman to now this, we do not want a house style; we want each film to be distinct and have its own look and its own style. This film certainly presented an opportunity - because it was an entirely different kind of setting, it’s not a contemporary American story, it was set in this kind of Dickensian world – to do something different. Because of the technological developments that we had with the rapid prototyping and then on ParaNorman we did the color 3D printing where we get more life-like textures and greater verisimilitude, we thought that on this project we really wanted to try to do something that pushed the color and the design on the faces, and that ended up flowing into the whole world. You can see with these characters, just the color that we ended up putting on these faces, it’s not naturalistic at all, it’s really impressionistic, you have these weird blues and reds right next to each other and then you see that kind of in the entire world. You see on these buildings, we have all these strange colors butting up against each other, but when you see it all together, it feels right, and that’s the world that we developed around this, which is one of the fun things and the challenging things, and exciting when you get it right.

Why stop-motion animation? What is it that makes you want to keep doing it when the rest of the world seems to like computer animation?

Knight: Yes, and I like computer animation as well, and we actually do incorporate CG elements into our films, but for me it harkens back to when I was a kid and I would watch the Ray Harryhausen creature features. There was something at that time, and it remains to this day, that was kind of magical about the whole thing. You’re watching this thing and it looked weird and it had the sense that it was something real, it was bathed in real light, but it moved in an unusual way, and it was almost this sense of a child’s plaything being brought to life. I always gravitated to those sorts of films as a kid. I just thought they were just beautiful, and really interesting, and magical. As a grown-up now, it’s the same thing. As I walk these corridors and look into these sets and see these things being brought to life, it is kind of a sense of magic.

I think it goes back to the genesis of the entire artform. When you look back over 100 years when stop-motion was really at the dawn of cinema, a lot of the ways it developed was you had stage magicians who were looking to bring their illusions to life, and one of the ways they did that, at the time, was through cinema and stop-motion. They developed these processes. And I just think it gives the whole thing just a dusting of this kind of magic. I think you can’t separate the process from the art itself, because if there’s one thing about stop-motion it’s that when you’re watching it on screen, it’s one set of hands that brought that whole thing to life. There’s a whole army of people who support it, but in terms of the animation performance that you’re seeing, there’s an artist who coaxed a performance out of this thing, and hopefully at some point you stop seeing the process and you see these things as living, breathing creatures that you connect with. And I find that an amazing process. It elicits beautiful results that you can’t get in any other medium.

What does the future hold for Laika? Do you see yourself branching out from feature films into any other arena? Or are you just going to stick with feature films for now?

Knight: Yeah, this is certainly our focus. Boxtrolls is our third film. We’re in pre-production on our fourth film right now, and ultimately we’re trying to shrink the window down on our release schedule so we’re putting out a film a year. It’s challenging ; no stop-motion animation house has ever been able to do that. It’s really tricky, but I think we’re very, very close. We’ll start shooting our next film sometime this summer, and then we put our following film after that into pre-production this summer. So we’re very close to being on an annual release schedule. That’s a big enough challenge for me.

Can you comment on your partnership with Focus Features as well? You guys have gotten a lot of recognition for your last two films, so it seems like a solid partnership that only has room to grow.

Knight: Yeah, I agree. We have a great relationship with Focus and Universal, their parent company. When we first shacked up with Focus however many years ago, seven, eight years ago, they had never done any animation … actually, nor had we, we’d never done a film either [laughs], but they had a history of doing really interesting work in film. I think they’re the bravest studio in Hollywood. They had done incredible work with really challenging material in the past, and it felt like what we were trying to do within animation, which is to tell bold, distinct, unique stories. They were the perfect partner for us and they’ve proved to be that over the last six, seven, eight years. Having Universal as the big brother on top of that, they’ve been incredible, too. We’ve forged really great relationships with all the partners over the years. We hope it continues on and flourishes as it’s done in the past.

You’re CEO, you’re lead animator, are you going to direct a feature?

Knight: I think at some point. It’s sort of cliché that ever artist wants to direct something, and I’m certainly no exception. It’s really about making sure I can manage it all. I got my hands full. When I’m able to focus on the right story and able to carve out the kind of time that I would need to do that, yeah, absolutely.

I’m curious about the distinction. Obviously, on a live-action feature, everyone knows what they’re doing. How do you portion out your responsibilities as far as lead animator versus, I believe you have co-directors on this film? What are their responsibilities? It seems like you and the other animators have individual scenes or sequences that they’re responsible for, so how does that all tie together?

Knight: Yeah, so the way we work on our films is, I think, a little bit different than most other animation houses. A lot of times with shots, because of the pressures of production, you just end up throwing warm bodies at shots; you’ve just got to crank through it. And we did that to a degree on Coraline. In those sequences where we, for whatever reason, we had a single animator handle an entire scene, we found that those scenes had a kind of spark that some of the other work didn’t, and it makes sense. When you allow an animator to focus on a portion of the film and really understand the arc of the scene, what’s happening with the characters, they can make choices all along the way that reinforce the main points of the scene. They really get to know what’s happening. Versus throwing an animator on a shot somewhere within a scene, they just have to crank through and do the best job they can, but really not having a sense of where it connects within the overall structure. Taking the best parts of that, on ParaNorman we basically divvied it up giving animators entire chunks of the film, and we’ve continued that on Boxtrolls. I really think it helps to give unique personalities to these sequences and these characters. You really feel like it came from one mind and one set of hands.

So that’s generally how we try to schedule and structure the framework of it. Tony and Graham [Annable] are directing it, I’m producing the film with David Ichioka, and I’ve got my hands in everything, I’m sure to everyone’s annoyance. I’m meeting with those guys all the time trying to figure out the best way to bring these things to life. This film was very difficult to get off the ground, but once we got into it, all kinds of innovations and new ideas came out of it, and I’m really, really pleased with the way it all came out.

Have you released what your next film is yet? Have you teased that at all?

Knight: No, no, we haven’t spoken about that yet. It’s a good one.

Without giving anything away, is it something along the lines of Boxtrolls that may be new to an American audience? Or is it more of a popular property that people might be familiar with already? Or original?

Knight: Well, to that point, the sort of things we have in the hopper that we’re developing are adaptations of literature and original ideas. Boxtrolls and Coraline based on literary properties; ParaNorman an original idea that we developed here. And so that holds true for all the things that we’re developing. I think that the main thing that excites me about the next project and the projects to come are that they’re totally different from anything that we’ve done and, I think, totally different from anything that anyone’s doing. For me it goes down to what’s special about animation. We’ve all heard people say that, “Oh animation’s not a genre, it’s a medium,” and it’s true, but people continue to treat it as a genre. We continue to see these regurgitated stories and these formulas again and again and again. And it’s disappointing. As a life-long fan of animation, it’s just disappointing. I think there are so many more interesting stories to tell that you can get a lot of rich stuff out of just by stylizing them, visualizing them in animation, that it just feels like it’s wide open. It’s disappointing as a fan that no one’s doing it. As a studio, we’re in a position where we can do something about that. So we really try to find those stories that have something meaningful to say and have that rich, dynamic storytelling, and then bring them to life in the best, most unique visual way possible. So when you look at the three films that we’ve done and I look ahead at the films that we have to come, they all reinforce those ideas. They’re unique films. They have something to say that really gets under the skin; they have themes that matter. And done in a visually beautiful way.

Who do you see as the audience for your films?

Knight: I think that we target families, and of course that’s a fairly broad thing; that could mean a lot of things to a lot of different people. I certainly think that with Coraline and with ParaNorman, we say “families” with slightly older kids. Because of the intensity of those films, they were probably not appropriate for the youngest members of the family. Boxtrolls is not that. I think it’s broader. It doesn’t have some of the same level of intensity that Coraline and ParaNorman did, but it’s still got its moments where we go into places that most animated films don’t. But yeah, the films we make are intended for families and all members of the family, so that covers the whole gamut. But I think that we really try to bring a level of sophistication to our storytelling and the way we execute on these films, which I think is a little bit unusual in animation. What it means is that we are not calculatingly populist in our approach to these things. We are not trying to take a story and water it down so it hits all four quadrants, we’re just trying to tell a really wonderful story in a visually beautiful way that appeals to families, so oftentimes that means we’re making choices that we think is the strongest choice for the film that has the potential of alienating some members of the audience. But in the end, as artists, as filmmakers, what we have to do is make the strongest film possible, and we think we’ve done that in a way that does appeal to a wide group of people.

Is this the camera you’re using?

Knight: This is the camera. We’re using Canon 5Ds on the film, so it’s just this little prosumer camera with this giant lens on the front. Over the course of this shot, we’re on this motion-controlled crane, the camera backs all the way up until it’s kind of back here beyond the set, which is why this is all open like this, and we’re really, really wide on this shot, so that’s why we’ve got this ridiculous lens on the front. But yeah, we shoot the whole thing with these things you can go into any camera shop and buy.

Are you doing the 3D natively or are you converting it later?

Knight: Oh, we don’t do any of that conversion nonsense. [laughs] That’s for suckers, right there! That’s for amateurs! No, we shoot the whole thing natively in 3D. It’s a huge difference. I think that, as an industry, I think 3D has been handled very poorly. It’s the possibility to tell a story in an interesting way to really add to the arsenal of the filmmakers, or you can use it as a schlocky gimmick, and I think in large measure it’s been used as a gimmick. The post process is a prime example of that. Those films were never conceived of as 3D films, they were never shot as 3D films, they were post … they put a little thing at the end of it to try to fool the audience into thinking they were getting a 3D experience, but there’s no sense of how that fit with the overall story and the arc of the film.

With our films, we start at the beginning and try to figure out how 3D can enhance and enrich the experience, so you chart it from beginning to end, just like you have a script for the story or a color script for the look of the film, we have a 3D script where we chart where we’re using 3D, and to what level, and for what reason over the course of the entire film. Before we shoot a shot, we shoot an entire 3D wedge where we dial in how much of that depth we’re using. On Coraline, we’d never done that before; no stop-motion company had ever done that before. What we figured out was, through a lot of trial and error, that the distance that the camera had to travel from the left image to the right image, because you can’t smash the cameras next to each other since they’re too big for this scale, was actually the distance between a puppet’s eyes. So every single camera is on, even if there’s no big motion-control apparatus connected to it, every single camera is on a little micro-mover, which means when we take a frame, it takes the first image and then slides over just slightly to take the next image, and then goes back to the first one.

So you can check it as you’re shooting it?

Knight: Yeah, yeah. I don’t. [laughs] I trust that it all works at this point. And it has. It hasn’t really let us down. But I do think that 3D is something that I think has not been used in the best way, generally, in our industry, and we continue to try to fly the flag for why it can be.

I think that when you see something that uses it really well, for instance Gravity, the difference is huge compared to the gimmicky stuff.

Knight: Yeah, I mean, Gravity works as a film on its own without that, but I agree that when you add that extra layer it enhances the experience, and that’s the same approach we take on our own films. You can watch this thing in 2D or at home on your big-screen TV and it’ll work just fine. That extra 3D element is something that we thought very hard about and really tried to incorporate in a way that enhances the storytelling. We think it does.

Now the advances in technology – everything from the puppetry, to the cameras, to the visual effects – do you think it’s gotten to the point that it’s easier or more daunting for an amateur stop-motion artist at home to break into something like this?

Knight: I think it’s way easier. I’m thinking about when I was a kid and there were absolutely no resources in terms of figuring out how to do this sort of thing. So a lot of animators of my generation all have the same story: we set up in our parents’ basement or garage or whatever with a little camera and tried to figure out how this thing worked. There were virtually no books on how to do stop-motion, the Internet didn’t exist as a resource. Now, you can shoot stop-motion things with webcams and free software and there are tons of resources and books on the internet that you can get to figure out how these things are done. Even for us, we put tons and tons of “making of” material just out there and then on our DVDs just to give a sense of how this process is done. None of that stuff existed when I was a kid, so I think for any kid who’s interested in this now, they have tons of opportunity to get into it … but you’ve got to be a little bit weird. [laughs] It’s a requisite thing.

Is that why you’re here in Portland?

Knight: Portland, I think, has a vibe that is consistent with the kind of vibe that this company has, so I don’t think it’s any accident that we’re here.

How long have you been on this particular set and sequence?

Knight: This is kind of a one-off. It’s a big shot. It’s towards the end of the film. I rehearsed it. We shoot every shot at least twice on twos and on fours. A second of film has 24 frames, so if you shoot something on twos, that means you’re taking 12 images. Essentially every other frame. And if you shoot something on fours, you do the math. So we rehearse these things as roughly as we can either on twos or on fours just to get the basic choreography of the shot, and then we go and sit with the directors in editorial and talk through the performance. Are we hitting the marks, are we getting the emotion of the shot, is there anything we need to change. If we’re wildly off the mark, we’ll rehearse it again, but if it’s basically right with some adjustments, we’ll go shoot it for real. We shoot the whole thing at once, so we shoot every image of that 24-frame cycle. Which essentially means you really only get one shot at one of these things. We really very rarely do reshoots. It’s one of the frustrating things about stop-motion, but I think it’s also one of the wonderful things about stop-motion, that when you’re watching a shot or a film, it really is a performance art. You start at one place and you end at another, time is warped and everything; while this will take 45 seconds for the audience to watch, it’ll take me three weeks to shoot, but from start to finish, I was bringing that thing to life. There’s no going back and tweaking and changing and modifying, it’s like what you’re seeing is something that came out of my hands over that period of time. I think that gives this thing is core humanity, which is really tough to see in other mediums.