Two years before Jerry Sandusky would tarnish its name with one of the most horrific serial rapist cases in modern history, Penn State didn’t seem all that different from any other major college football town. Reasonably priced restaurants smattered the town right below the campus, as did a number of record stores, caverns of used books, coffee roasters, and one absolutely bitchin’ arcade. This is the place where I first discovered college radio, weed, and buffalo wings. It’s also where I got my first whiff of Twin Peaks and David Lynch.

In 1992, while my parents went to see Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, I was busy guffawing through Honeymoon in Vegas – they were, and remain, big proponents of seeing movies alone. My movie got out a bit earlier and being naturally rambunctious, I made my way into the back of their theater to watch Leland Palmer (Ray Wise) butcher his own daughter, Laura (Sheryl Lee), in an abandoned train car in the wilds of Washington State. Genetics are inarguably the reason I’m bald but if that weren’t the case, that sequence would have done the trick right there.

It’s not just the fact that Leland, inhabited by the nefarious spirit known only as Bob (Frank Silva), took a knife to his only daughter after raping her for what might have been some six years. It’s the manner in which Lynch depicted the scenes in visceral flashes of terror, lit sparingly and filled with a caterwaul of screams and bellowed pleas. Scored by Angelo Badalamanti and shot by Ronald Victor Garcia, the sequence doesn’t so much feel as if it’s unfolding but rather being let out of its cage, shrieking the horrors of ordinary America at the top of its lungs for nobody to hear.

Booed at Cannes and largely dismissed at the box office, where it placed well behind forgotten relics like The Mambo Kings and Dr. Giggles, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me’s hallucinatory, skittering style would lay the groundwork for Twin Peaks: The Return, both in form and narrative. In Lynch’s Showtime series, which just concluded and will remain the best series of this year by a mile, much of what Agent Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan) must go through to reunite with Laura (or something like her) can be traced back to what happens in Fire Walk With Me. The penultimate episode of the series even borrows a large portion of the movie’s final 30 minutes in enacting the final attempt made by Agent Cooper to rescue the young girl whose death first brought him to Twin Peaks.

Cooper was only seen sparsely in Fire Walk With Me, but his scenes also set up his strange, unyielding relationship to Laura Palmer and his connection to the inter-dimensional underbelly known as The Black Lodge and its various corridors. At first, he speaks with Agent Gordon Cole, played by Lynch in both the film and the series, about a dream he had that seemingly made him question his own existence. In another sequence that The Return borrowed, he met a confused and angry Agent Philip Jeffries (David Bowie), who does not trust Cooper and refuses to speak about the elusive “Judy” in front of him. A sudden flash to the Black Lodge, where the Man from the Other Place/The Arm (Michael J. Anderson) demands his “garmonbonzia” while Bob cackles away and an early incarnation of one of the now-iconic Woodsmen (Jürgen Prochnow) slams on a table, and Jeffries seems to evaporate into thin air. Later on, Cooper seems to prophesize the murder of Laura Palmer to Albert (the late Miguel Ferrer) while sitting around the FBI Philadelphia office.

The Jeffries scenes seemed to be of particular importance to the narrative of The Return, alluding to the dual nature that Cooper would come to embody in forms ranging from the evil Mr. C to Dougie Jones to the unknown Richard. (Jeffries is also recreated as a talking, smoking oversized kettle of sorts, able to direct visitors to the Black Lodge with series of numbers.) Was Cooper’s multiplicity apparent to Jeffries that far back? The purposefully disorienting way that Lynch cuts the entire sequence between the FBI offices and The Black Lodge suggests not only ties to the otherworldly but also how its powers and uncharitable rhythms can infect you and tear you apart from the inside out.

Perhaps the most crucial element to carry over between the movie and the series is the Owl Cave ring, the green ring with intersecting peaks in the middle. When agents Chester Desmond and Sam Stanley (Chris Isaak and Kiefer Sutherland) turned up in Portland, Oregon to investigate the bludgeoning murder of Teresa Banks (Pamela Gidley), they noticed the absence of a ring on her hand, and it wouldn’t be found until Desmond discovered it placed nicely on a pile of dirt in the Fat Trout Trailer Park, run by Carl (Harry Dean Stanton). While he searches for that ring and clues to Banks’ murder, we first hear about the Chalfonts – or the Tremonds - whose names would come up in the final moments of The Return as former and current owners of 708 Northwestern St.

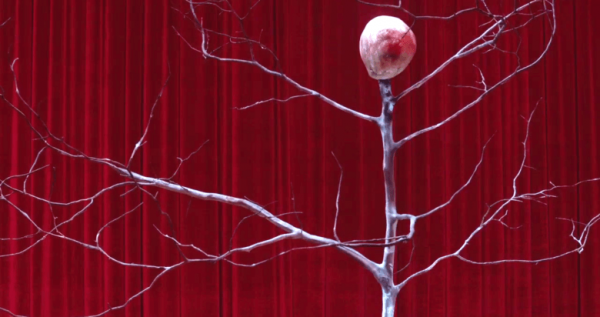

The ring acts as a sort of connective point between this world and the inter-dimensional realms of the Red Room, the Black Lodge, and the White Lodge, but its power is primarily evil. When Stanley and Desmond speak with the waitress at Hap’s Diner, she talks about how a ring made Banks’ arm go numb, a fact that comes up often in the original series and The Return and nods towards Philip Gerard’s (Al Strobel) decision to cut off his own arm to escape his sadistic, maniac tendencies. It’s both a symbol and an active agent, like much of what Lynch shows in the movie and in the TV series, for instance Cole’s “mother’s sister’s daughter” with the blue rose. These symbols can also be living things that act of their own accord – not unlike the Buddhist concept of tulpas.

For all the similar elements that run through Fire Walk With Me and The Return, the moods they create are disparate. Fire Walk With Me has the feeling of suddenly discovering and being overwhelmed by evil and madness thanks to the fact that it has 137 minutes to get its point across, while The Return unfolds over a 14-hours-plus runtime. The difference in style and pace feels decisive, however, reflecting the difference in Lynch’s age and artistry. Fire Walk With Me is a timed swim in a lit pool of gasoline, a constantly roiling and self-questioning expression of the dream we live in, per Agent Jeffries. The tone is that of unresolved, bellowing anger, frustration, and anxiety. The Return, in comparison, is funnier, more deceptively laconic, and epic in scope, a sublime and haunted odyssey through dimensions and different personages in the hopes of fixing a cosmic injustice.

The repetition of symbols, words, characters, locations, music, and actions is meant to send people (like me) scrambling to connect the innumerable dots, but the purpose of this mélange is bigger than that. Cooper’s need to not just resolve but undo Laura’s death keeps him running in circles, stuck in the same place even as he travels through unspeakable worlds, repeating the same actions even as his friends and colleagues age and old symbols reappear in new places. Even as The Return leaves us at the same doorstep where this all happened, Cooper tragically still can’t seem to grasp change, if only because the world seems to constantly remind him of his lack of true knowledge and his devastating powerlessness against the ravages and indignities of time.