[NOTE: This is a repost of our review from the 2016 Toronto International Film Festival; Una opens today in New York City and October 13 in Los Angeles]

The case of sexual abuse laid out by Una is one that’s difficult to untangle. Morally, there’s nothing complicated about who’s responsible, but director Benedict Andrews is constantly trying to push his film into grey areas where we can’t unrepentantly hate the perpetrator, nor can we completely understand the victim’s motivations because she doesn’t even seem to understand those motivations herself. It’s a film that’s all about confrontation without resolution, and it forces us to be unnerved with the knowledge that neither character has any hope of finding peace.

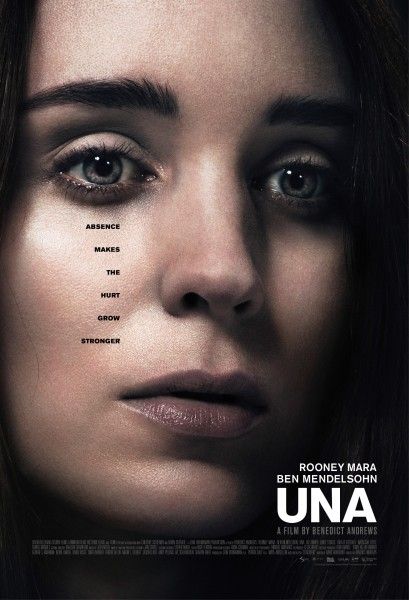

When she was thirteen years old, Una (Ruby Stokes) had a sexual relationship with her adult neighbor, Ray (Ben Mendelsohn). Ray was eventually convicted of sexual assault, and has since moved away to start a new life under a new identity. Una, now a traumatized adult (Rooney Mara), seeks out Ray, now working as a warehouse manager under the name “Pete”, and confronts him about their relationship. Una wants Ray to know that he ruined her life, and Ray wants Una to know that he’s not a pedophile. They’re two people talking past each other about a past they can’t even agree upon.

There’s no question that Ray did something wrong. He was the adult, Una was the child, and while he may have even convinced himself that he “loved” her, he still took advantage of a young girl. It’s a testament to the film’s script and Mendelsohn’s performance that we’re willing to even consider him as a person. Una isn’t trying to re-litigate the case or even make Ray sympathetic as much as it doesn’t want us to easily brush him off. The movie makes great pains to understand his psychology, and it turns the question away from “Was he wrong?” (because of course he was) to “Is he a predator or a guy who made a terrible mistake?”

For some, Ray’s actions are enough to dismiss him, but I admire that the film tries to paint him as a deeply-flawed human rather than a monster. It’s easy to label someone a monster and move on, and Una is never easy. Every time the film could go for the expected, it turns on a dime. Not all of these twists work, but it keeps us on our toes, which makes the situation feel real because it’s working against what we want to happen. This is a messy, twisted relationship, and Una wants us to live in that mess.

The film also refuses to let Una’s victimhood be predictable or simple. She tells Ray that she hates her life, but it’s never clear why she’s confronting Ray in the first place. Is she looking for an apology? Does she want him to know how much she’s suffered? Una doesn’t seem sure herself, so she’s charged in without a plan, and without a net. Mara perfectly balances the character’s anguish with her anger, and paints a complex portrait of an abuse survivor whose mental wounds have never come close to healing.

Screenwriter David Harrower adapted the screenplay from his stage play, and you can easily see how this was story was contained to a stage. Andrews does what he can to make the story more cinematic, and there’s some impressive cinematography and strong use of editing in flashbacks, but it never completely shakes off its staged origins. There are also times where the plot can be a bit heavy handed like Ray frequently hiding from his boss just like he’s figuratively hiding from the consequences of his actions.

Nevertheless, Una is still a fascinating conflict that would be worth seeing on stage, and especially on screen when you have Mara and Mendelsohn in the lead roles. While the film doesn’t always succeed in playing against expectations (especially near the end as the story seems as lost as Una with how to proceed), it forces the audience to sit with tough questions even when we think we already know the answers.

Rating: B+