Underrated is a term that is frequently misused by both film fans and critics. In an age where we view constant feedback on the Internet if something isn’t universally praised or awarded and we’d like it to be, we often bemuse it as underrated. What underrated should mean for a film is that it receives wide distribution but is left out of that larger discussion from both audiences and awards and critics allow the aggregate Rotten Tomato and Metacritic scores to become the end of the discussion as being liked within their community.

Perhaps I’m setting myself up to use this term incorrectly too with this piece, but ultimately, I’d just like to elevate a few directors who are doing very interesting things in an industry that’s constantly being referenced as creatively bankrupt in America.

When it comes to modern American auteurs, we’ve created two levels of excitement. There’s the universally agreed upon by fans and critics that any announcement of a new Paul Thomas Anderson, Wes Anderson, the Coen Brothers or David Fincher film is met with salvation. That’s our trifecta that’s pointed to for our absolute best talents within the medium by both fans and critics. Then there’s the second level of filmmakers who are immensely championed by critics and have their sizable fans within the cinephile community but have a little bit more of a colder view from the mainstream public, like Kathryn Bigelow, Sofia Coppola, Todd Haynes, and Quentin Tarantino (who really exists between these two planes, as someone who’s immensely lauded as an auteur but also receives criticism for his lifting from previous films made by others) as a few examples. For all the hand-wringing from both fans and critics about the future of cinema, how foreign directors are making the best Hollywood films and what that means for our identity within the film world and, of course, the studio’s corporate interests to just make remakes and sell movie universe maps these directors are our bastions of salvation for the American film industry.

But there are many other directors who are making great American films and have not been elevated to the prestige event film status that everyone above has to some level. Because the names below are not agreed upon as “must see” as soon as their films are announced like the names above, we’re labeling them as “underrated” at our own peril.

Below are five fully vetted American auteurs whose every film should be looked forward to with great anticipation. To land on this list, I’ve cherry-picked the number of three films minimum, because to be an auteur (verified blue checkmark), one has to have established a stylistic theme in their filmography, whether that’s the type of narrative or a specific sepia-toned look. And because this list is built in to tie into a specific director with a new film out this week, James Gray, his auteur mantle defense gets the most attention. And why are we focusing on nationality? Outside of accusations that the American film industry is creatively bankrupt, that’s how Cannes rewards the Palme d’Or—to the country of the winning director, regardless of the language spoken or which country funded it —and hey, the French invented the term “auteur” and they’ve have propped up Gray with two decades of support at their festival. (Peep the amazing Cannes 2017 lineup here.)

James Gray

When James Gray is written about as an under-appreciated American director usually it comes with one of two follow-ups. A) That he’s adored by French critics (like he’s the dramatic version of Jerry Lewis) or B) That he makes cinema that’s more akin to the 70s and his pacing is less digestible for modern audiences who’ve now primarily grown up with junk food. He’s addressed both at length in interviews (often very candidly and with great wit; seriously this guy would make a great comedy some day) and even said that he tries to emulate the best filmmakers of the mid-70s, such as Martin Scorsese, Sidney Lumet, Francis Ford Coppola and Stanley Kubrick. I’ve used these questions in interviews him as well, it seems appropriate to discuss why a director who’s had four films debut at Cannes has never been considered one of the greatest working talents stateside.

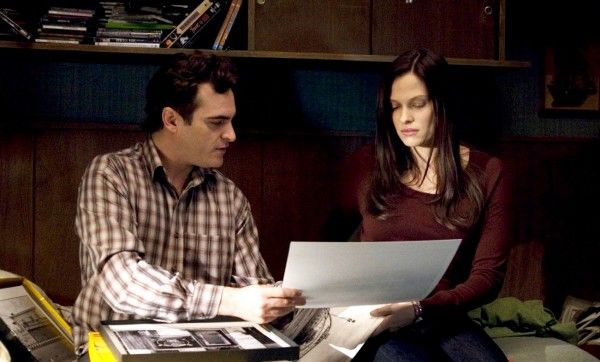

Gray has had numerous films go through nightmare releases where the distributor wants drastic cuts in the running time and if Gray obliges (such as The Yards and We Own the Night) there becomes pacing problems and when he doesn’t (such as The Immigrant) the distributor basically holds the film hostage and only gives it a soft and spiteful rollout. In another instance the star (Joaquin Phoenix, who’s appeared in three Gray films, but for this parable it’s Two Lovers) announced his fake “retirement” from acting after the world premiere and thus buyers—already weary of indie films in 2008—were less inclined to buy. Two Lovers, which would’ve easily found a home at most other Cannes festivals, which was produced by Mark Cuban and ended up settling for his passionate micro-distributor, Magnolia, when it was attempting to partner with a larger distributor didn’t have the funds for a proper auteur-sized rollout and Phoenix was promoting the film while in his bearded-weirdo rapper performance art stage (queue the David Letterman clip), so it never stood a chance with the general public.

It’s easy to stack up a poor-James-Gray narrative because he’s so beloved by the French but the industry has changed so much it’s impossible for him to find that adventurous movie-going audience that used to thrive in the 70s. But let’s look at what makes Gray an auteur, which is more than his eye for immaculate shots (the ending of The Immigrant is not only expertly performed by Phoenix and Marion Cotillard, but it’s a perfect visual metaphor and a very tricky shot to pull off and describing it would spoil the movie, but hot damn, watch it) and his penchant for patient pacing that allows for moments to happen and not just push plot points forward. His narrative focus on family and the delicacy of bloodline relations that makes everything in life harder—even though it tethers us to something grounded—is what gives him that extra auteur sheen.

Gray’s films are fraught with delicate familial issues that range from complete dichotomies, such as the criminal underground leader in We Own the Night who actually hails from a family of cops, to something that’s less harmless but still aggravating, such as the overbearing family who constantly checks in on their son’s well-being in Two Lovers (thus continuously infantilizing him). Gray focuses on the outsider of the family, someone experiencing grief, or someone who has made life decisions that separate them from the family. And that is a painful place to be. As such, let’s look at Gray’s distribution and stateside recognition troubles as growing pains of the triumphant return of the outsider child who proves everyone that they were wrong to doubt him.

This week it’s fitting that his newest film The Lost City of Z will open (in “select theaters”) the same week as The Fate of the Furious, a film franchise that has reinvented itself to be about family dynamics in order to separate itself from the pack of bam-bam action films. (If they say “family” enough everyone will pick up on it, right?) The Lost City of Z has bloodlines running through it, but Gray plays it subtle. When a military man and adventurer, Percy Fawcett (Charlie Hunnam), takes a map survey job to divide Bolivia and Brazil so that there will be no war (but rubber keeps them profitable) he’s told that by taking this job he will be able to reclaim his surname which has kept him back from past promotions due to his father’s reputation. It’s a line of dialogue that doesn’t give us information of what his father exactly did, but instead focuses on the knowing receipt of those words on the part of the son who’s processing it. He knows his reputation has preceded him and he knows only he can undo it. But that’s not the only familial bond in Z. It’s the pronouncement of staunch gender roles in an otherwise idyllic-seeming marriage between Percy and his wife, Nina (Sienna Miller).

In one breath he champions Nina’s discovery of a correspondence from more than a century ago that partially confirms a lost city he thought he’d discovered in the Amazon, but in the next he tells her she cannot join him on his next voyage because she needs to tend to their children. Years later, he takes his oldest son (Tom Holland) back to Brazil in an attempt to find what he’s labeled as “Z,” one of the earliest civilizations in the Americas. And in the Fast and Furious way of things, Fawcett also makes new “family” bonds with those whom he shares years on wooden rafts with (Robert Pattinson and Edward Ashley).

The Lost City of Z is an extremely well-paced film that spans decades but never feels like it’s rushing to its conclusion. Gray chooses to focus on Fawcett’s various bonds to his family, his discovery, and his fellow man and how those tethers get him through various stages of life interruptions, whether it’s World War I or floating the Amazon. In my eyes, this is the third masterpiece that Gray has made in a row. But what’s most important is that with this release, he has the full support of the studio behind him (fittingly, Amazon Studios). They’ve held junket days in two cities, they’re rolling out numerous Q&A screenings, and they’ve marketed multiple trailers and posters; they’re treating this film as an event, which has not happened for Gray stateside.

For Gray’s previous troubles with distribution The Lost City of Z truly feels like the narrative of the prodigal son who has returned and is this time acknowledged. And his next film, Ad Astra, already has Brad Pitt lined up and ready to shoot this summer. It, of course, has a family element as Pitt is going on a one-way mission to Neptune to find why his father’s previous mission failed. And with Z’s executive producer (Pitt) already attached, Gray has to feel that the support of the American film family is finally behind him all the way.

Essential Films: The Immigrant, Two Lovers, The Lost City of Z (read our full review here)

Spike Jonze

It might seem strange to include an acclaimed Oscar-winning writer-director on an “underrated” list, but Spike Jonze was so closely associated with Charlie Kaufman’s brilliant scripts that the touch he brought to the material didn’t gain as much attention as the what-the-fuck? buzz that came with describing the plot to Kaufman’s script for Being John Malkovich. Nor was Jonze the focus of attention surrounding the that-was-the-most-bizarre-book-adaptation-ever! praise that came with Kaufman’s script for Adaptation. Don’t get me wrong, Jonze directed the hell out of those two movies. Other directors (including Kaufman himself) have sometimes failed at reining in the unusual and creative dalliances that Kaufman strings together that can lead to pure chaos. Jonze had a knack for creating a realm of controlled mania—but his sterile lens went under-appreciated in comparison to the immense praise that Kaufman received for the ideations.

In fact, Jonze deserves some applause for taking the more sterile and grainy approach to Kaufman's scripts because they were so out there that his less showy work helped ground the films more. Even the fantastical insert into another person's brain in Malkovich was shown akin to looking through the tube of a paper towel roll. Never has the desire to be another person looked as hollow as that desire actually is.

Jonze’s first outing without Kaufman was a beautifully designed, sun-drenched therapy session made from a beloved children’s book, Where the Wild Things Are. It has its defenders, but most found it lacking in narrative. Wild Things marked Jonze’s first feature-length script credit (shared with author Dave Eggers) but it was his next film that would become his most personal and heartfelt and thus his best. Her, for which he won a Best Original Screenplay Oscar, has absolutely cemented Jonze’s status as a major American visionary who’s every bit as unique and imaginative as Kaufman. Her is absolutely perfect from beginning to end.

However, one distinction between Jonze’s early work and his later solo work, in both Wild Things and especially Her, there is a tenderness and emotional intelligence that was absent from the more nihilistic Being John Malkovich and Adaptation. Jonze’s two most recent films have revealed him as a sensitive man who wants to feel connected to people, even though the compulsion to say that modern society (and perhaps genius screenwriters) have made it impossible to connect. Whether it’s through visiting communal-living beasts in an alternate realm or a computer’s voice that’s been programmed to adapt to its owner, Jonze uses the peculiar (yet familiar) to push his characters back into the arms of their human friends and families for true fulfillment.

Essential Films: Her, Being John Malkovich, Adaptation.

Mike Mills

Mike Mills came to filmmaking from the art and design world. His first film, Thumbsucker, was an adaptation of a book and as such he was detached from the material. His artwork, even if it’s just an assemblage of images from a specific year, is very personal. Thumbsucker in all it’s indie-coolness didn’t prepare us for the immense and craterous depths of his soul that Mills would take to with his next two films, Beginners and 20th Century Women.

These films aren’t just personal because they draw from his personal life but it also draws from his years of artwork. The way he frames human experiences through objects, music, design, and cultural asides to comment on what’s happening in the world and how that informs his characters. He keeps his characters close and then zooms out to acknowledge the rest of the world before honing back in on his particular people. In Beginners, while the Mills stand-in (Ewan McGregor) deals with the death of his father (Christopher Plummer) Mills zooms out to experience part of his father’s decades, with Neil Armstrong on the moon and home videos of families reaping the benefits of The New Deal. He elongates this technique in 20th Century Women, giving each character their own personal history chapter from the Great Depression to a commune. This technique removes any navel-gazing critiques because it doesn’t feel like a gimmick but a genuine extension of his own experience in relation to the personal stories of his father’s coming out to him as an 80-year old man in Beginners and his mother’s (Annette Bening) ask of his female friends to help raise him to be a good man in 20th Century Women.

These simple-seeming stories are enhanced by Mills’ immense details of time and place and how specific essays, books, music and mixed tapes provide a new worldview. And how that worldview can run counter to the larger world outside of these gifts. They’re small asides, but the asides add personal circles to characters that already feel fully formed. And it’s deserved because the extra attention allows the audience to feel Mills’ expanding heart for the people who’ve shaped him.

Essential Films: 20th Century Women, Beginners

Laura Poitras

If we’re in a golden age of documentary, Laura Poitras is our absolute best investigator in the medium. What makes Poitras a great documentarian is that she dives in to complicated subjects not to find one specific damning item, but to provide a balanced and personal look into frightening subjects on a personal level. What makes her a great filmmaker is that she’s able to take subjects such as jihad, government-sanctioned torture, and government surveillance and present a personal narrative while also editing it like it’s an actual movie thriller.

The first two in a trilogy of films that document America’s complicated response to 9/11, My Country, My Country and The Oath, put Poitras on a global travel watch-list. That governmental overreach, plus her ability to receive some of the most candid responses from subjects ranging from American veterans to Iraqi doctors to jihadists who were extremely close in proximity to Osama bin Laden and the 9/11 hijackers, is what put her on Edward Snowden’s radar to reach out to her for one of the biggest stories of this century, the NSA’s surveillance of every American, in what would become Citizenfour, told in real time from receipt of that outreach to while the story is leaked to the press from a Tokyo hotel room. Citizenfour put Poitras in the narrative and it reveals her to be just as levelheaded and concerned with the directions that governments and business interests are taking globally.

Poitras’ films will touch a nerve on both the far left and the far right because she’s not out to prove any partisan ideals, but rather to uncover how partisanship doesn’t matter because our government is complicate on major infractions on each side in ways that effect everyone regardless of your political affiliation. Each film in this trilogy is about the various sworn oaths that individuals take and often break when the larger structure above them has broken oaths to the entire world. Under Poitras’ lens we see the ramifications of both large-scale lies and personal lies—but she isn't just interested in the thrilling aspects, Poitras pointedly allows time and space to understand the personalities and motivations of her subjects; she's never just moving on to the next thing, she listens, observes and gives the assurance that the full story will be told. At this juncture, a new Poitras film should be met with the same documentary event status that Erroll Morris has justified with each release.

Essential Films: Citizenfour, The Oath

Kelly Reichardt

Kelly Reichardt makes films that feel like the best short story in a collection of great short stories. That’s not a dig against her craft in the slightest. If you love short stories you know that the best ones are sometimes more impactful than a complete novel. It’s an incredibly impressive feat for a writer to pack in enough observations and economic choices about what to show in just a handful of pages. Because Reichardt’s films are so character based and based in a very specific arena of time that’s told not with flashbacks but in reactions or dialogue in that very moment, they feel like the most interesting chapter for the character’s we’re watching.

Reichardt is perhaps the only filmmaker on this list where each film is almost equal in quality. I’ve not seen her 1994 debut, River of Grass, but after she emerged from him her filmmaking silence a dozen years later with Old Joy, I’ve not missed any. Whether it’s a revealing camping trip (Joy), the financial fabric of a desperate woman unraveling en route to a lucrative summer job (Wendy & Lucy), a few days on the Oregon Trail (Meek’s Cutoff), an eco-terrorist plot to blow up a dam (Night Moves) or a series of Montana stories that range from building a home with the perfect rocks to an armed standoff with a man who’s body has been made less useful by the work that he’d done for decades (Certain Women), Reichardt is the penultimate cinematic voice of the Northwest. And like the great short story authors who’ve written in the region, like Raymond Carver, Sherman Alexie or Lucia Berlin, she uses silence and stillness to punctuate internal thoughts. Like those authors, usually big confrontational things don’t happen, but rather we meet the characters after they’ve been confronted so many times they’ve lost faith in their fortitude.

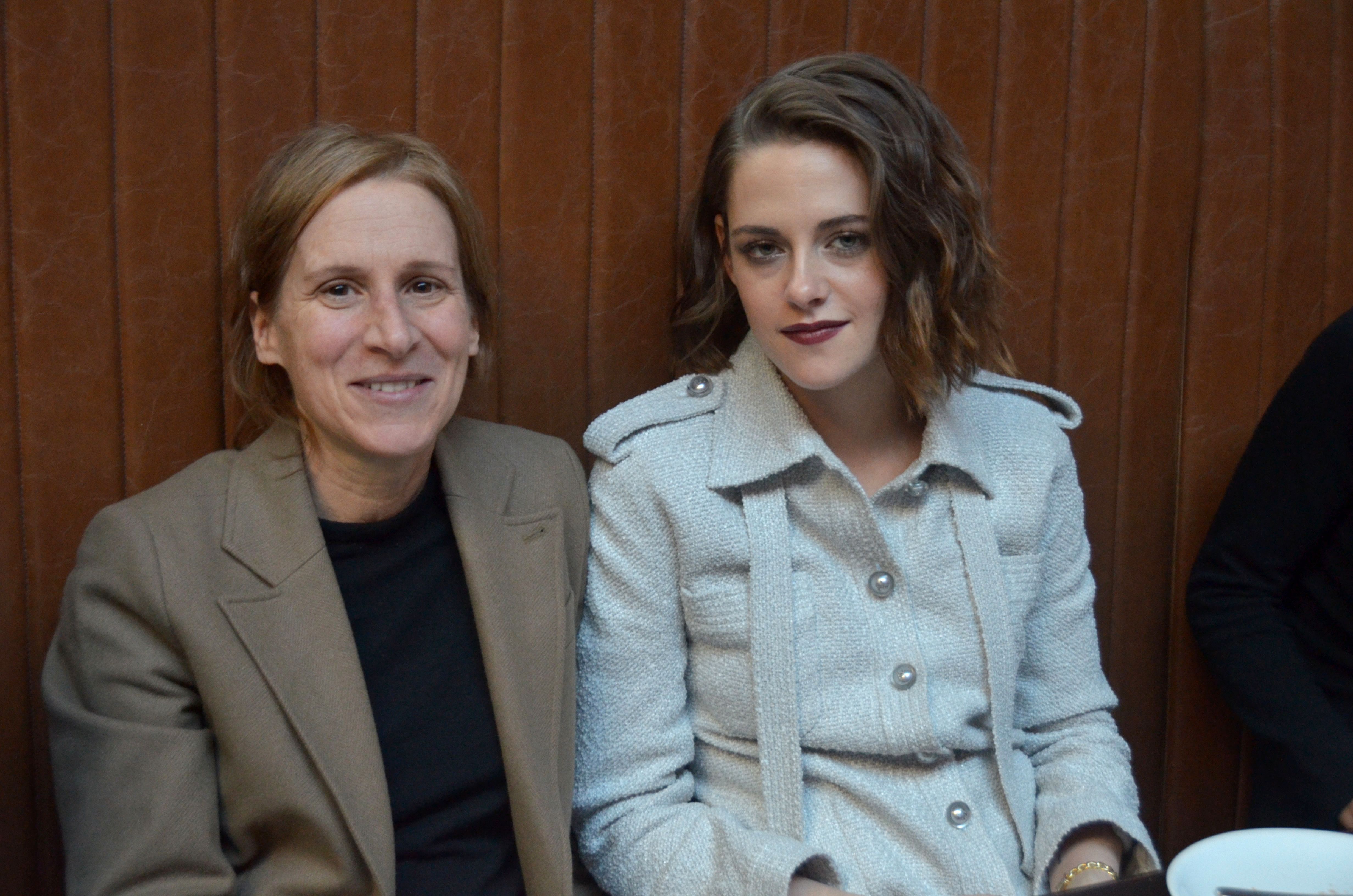

Reichardt is one of the best directors of performances working in American indie film right now. Her style rests on her portraiture and ability to direct silent moments in ways that we can all identify what that human behavior means. It takes brave and capable actors like Michelle Williams, Paul Dano, Laura Dern, Kristen Stewart, Jesse Eisenberg and Peter Sarsgaard and it unearths new talents like Lily Gladstone and Will Oldham.

Essential Films: Certain Women, Wendy and Lucy, Old Joy

Honorable Mentions

Honorable Mentions (Directors Considered for this List): Harmony Korine, Jeff Nichols, Joshua Oppenheimer, James Ponsoldt, Joshua Safdie and Ben Safdie, Jeremy Saulnier, Ti West and Adam Wingard.

Please let us know in the comment section who your favorite modern American auteur is and who you think should be mentioned as worthy of being elevated to that status.