Directed by Valeri Vaughn and produced/narrated by Vince Vaughn, the documentary Art of Conflict (available exclusive on Netflix on June 1st) is a fascinating look at the political murals that are so prevalent all over Northern Ireland, and that express the pain and conflict that the country has had to deal with, often in very provocative and striking ways. For the production, Valeri and Vince Vaughn spent long stretches of time in the North, interviewing politicians on all sides of the divide, to present these intriguing works of art.

During this conference call to promote their documentary, Valeri and Vince talked about growing up in the Chicago suburbs and embracing their Irish roots, what their first experience in Ireland was like, how much fun they had working on the film together, that the art is really the focal point of the documentary, the most difficult aspect of their research, how important it was to document all of these murals before they’re removed, what it was like to film in Northern Ireland, how the murals are viewed within the community, and what their favorite documentaries are. Check out what they had to say after the jump.

Question: When was your first trip to Ireland and what was the experience like?

VALERI VAUGHN: Well, we have Irish on both our mom’s and our dad’s side. The first trip to Ireland was later, and that was when Vince actually went over and got sparked with the idea for this documentary, by being a tourist there.

VINCE VAUGHN: I went with a friend of mine. I was filming a movie in London, and I drove through Ireland. It was quite beautiful, and the countryside was really remarkable. And then, we ended up going to Belfast and, when I was there, they asked me if I had seen the murals. I hadn’t even heard of them. They have a black taxi tour, which we show in the movie, where they drive you around in the black taxi and both sides know that you’re a tourist. It’s the safest way to visit and take in the art. The contrast between the countryside and Ireland, and the murals there, with Northern Ireland still being a part of the United Kingdom, there’s just a stark contrast in those two things. And I found that the art that came out of the conflict was really spectacular because it was about remembering either events or points of view for local neighborhoods, or the rallying cries of one side against the other. So, out of this very tough, very rough situation, which caused a lot of pain and hurt, on both sides, the art that was there was really being used to unify a neighborhood or to get ideas across. I found it to actually be very striking and interesting. So, I came back and told my sister Val about it, and Val had done some documentary work prior to her becoming a school teacher, and then a mom. I said, “Is this something that would interest you?,” and thankfully it was. So then, we went over there in a more traditional way and were able to get a lot of people together to talk to and interview, and really focus on the artist and the arts. In doing so, we learned a lot about the conflict and what was going on, on both sides, through looking at the murals that were painted in Northern Ireland.

What was it like to grow up in the Chicago ‘burbs, being Irish? Did you guys really embrace your Irish roots?

VINCE: We were part Irish, so we were always aware of that. Chicago always makes a big deal out of Saint Patrick’s Day, and there’s definitely a lot of community there. We had Irish ancestry in Chicago, no question about it.

What was it like for you guys to get to work together?

VINCE: It was a lot of fun!

VALERI: Yes, it was a lot of fun. It’s really a great opportunity, when you get a chance to work with each other, in this way. Being brother and sister, and being able to work creatively on a project, is really fantastic. We’ve enjoyed it.

VINCE: It was such a great journey, and a learning experience. It was fun to have someone that could really elevate you, and that you could enjoy and have fun with and take the journey with. I think it was really the subject matter that was rewarding to work on, and getting to know these people and their stories was really fascinating. A lot of people know that there’s a conflict going on over there, but the specifics aren’t as well known. And I feel like the murals haven’t really been a focal point before. A lot of people aren’t as aware of the murals, or the point of view of the art, or the conflict behind it.

Separate from the conflict, what would you say about the art of these murals?

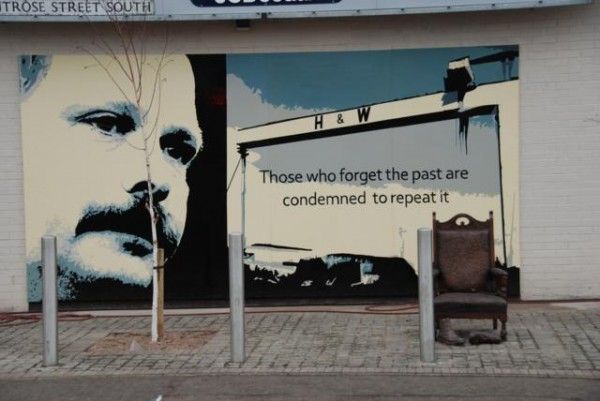

VINCE: The focal point of the documentary is the art. It’s unavoidable, though, to understand that there’s some political point of view behind it. But, we really tried to be non-biased and just let the artists or the people that were speaking talk about what their experience was. It’s from their mouths and their point of view, in regard to where these things came from. One of the murals that I found very interesting was the plastic bullet mural, where there were plastic bullets that were used to stop rioting, or just on the Catholic neighborhoods, and the reason behind it was that it was a fake way to stop the riots or just to deal with them, but kids were actually getting killed by the use of these bullets. So, I think what’s important to know is that they’re not paintings that you see in a museum. They’re actually in the communities and the neighborhoods. They’re on the sides of houses or buildings, and they’re actually a fabric of the neighborhood. They’re for the people who live there and pass through there. They’re either warning signs for people who aren’t welcome, so that they stay out, or they’re rallying cries for the neighborhood, or reminders of events that brought the community together. So, the artist’s choice of putting the faces and ages of the children on actual plastic bullets was a really gripping way to get his point across about the effects of these bullets and the consequences of using them. And that’s just one example of how the art is really used to express feelings or points of view that the individuals, on both sides, were feeling during the conflicts.

VALERI: The saying that a picture is worth a thousand words is true, when you see one of these visual images that are so provocative and so telling. The fact that they do come from the voice of the community that’s putting them out there, and that you have that voice on both sides of a conflict, was a nice way for us to get out of the way and just let those murals tell the story.

What was your approach in filming this? Were you just looking to raise general awareness, or was there a particular message that you wanted to portray?

VALERI: You know, we didn’t really start out thinking of it like that. It was much more organic than that. It just naturally came up. We were passionate about the story and wanted to tell it.

VINCE: Especially where the artists and the murals were concerned. I had never seen anything quite like that, where the neighborhoods were completely covered in these murals that ranged from threatening to keep outsiders out, remembering events that were terrible, battle cries, or rallying cries. The entire neighborhood, when you step into it, has living, active murals. They’re really a part of the fabric, and it’s an interesting thing to have, on a daily basis. That was the wall that divided these neighborhoods that kept getting built up, higher and higher and higher. I found it very unique. And so, our focus really became the art and the murals. We would look at the murals, and they would explain why they were that way and what the point of view was behind it. It was really from their points of view. What’s interesting is that there has really been a debate about the murals and whether they were art or informational, or whether they just simple war time propaganda. It was interesting to hear the different people tell their points of view on it, with why they were painting stuff, the events that made them stir enough to go paint it, and how they go about painting it. So, what we really focused on, in our documentary, were these murals and, in doing so, you get to learn about the events and the things that come out of it, but it was really just an investigation. We were going in and seeing something unique, whether it was a situation, a dynamic, or an art form that was what came out of this situation. We were very curious to go in and investigate, and find out how this came about and all the reasons for it.

VALERI: When we realized that the murals tell a story, that became fascinating to us. We thought, “Wow, that’s really something different.” You have mural communities in a lot of places in the United States. And outside of the United States, different mural traditions exist. But, it’s very rare to find one where they exist on the opposite sides of a wall that keep people separated, and where they’re using the murals purely to express themselves. They’re not communicating, verbally. They don’t see each other. They’re kept apart from each other over their differences, and yet they’re voicing themselves through this street art.

What would you say was the most difficult part of your research?

VALERI: Well, the conflict itself is quite complicated because it’s gone on for so many years, and it goes back so thick into history. So, a lot of people really will simplify it, in order to understand it. There is so much to it, like learning all the different terms and what they mean and the political side of each and what one perceives as history versus another. There’s just a lot to the conflict, and what I like about using the murals to tell the story is that it doesn’t complicate that process. It simply shows a moment in time when that mural was voicing what existed for the community.

Were you able to bring any levity to the production, when it needed it?

VINCE: Val was really the director of the piece. I feel like, in a documentary format, you’re really observing, so I wasn’t necessarily joking through the process. For us, we were really just enamored with the artists and also the history behind what happened. And what’s been amazing is that audiences have just responded really strongly to the piece. I equate it with blues music. Sometimes out of conflict or human circumstance that’s difficult, with a struggle or pain, there’s a way of expressing it through art, like music or, in this case, murals or paintings on the sides of buildings. There’s actually some really beautiful, exquisite, really interesting art that comes out of those things. It’s just a way to express yourself. So, for me, it was more about taking it in and observing this unique expression. Murals have been used by people before in conflicts, but I think this was a done in a very unique and very provocative way.

Since the murals come down and get replaced so quickly, how important was it to document each one for prosperity?

VALERI: Well, it was very important, obviously, but we didn’t realize that, when we were filming. We started filming long before they came down, or started to come down, so we didn’t even realize that we were documenting them. The thing with murals is that, because they’re painted on the side of houses, or in the neighborhood on walls or businesses, they’re not museum pieces. You can’t move them into a museum and keep them. So, photographing them is really the only way to keep them alive. And the fact that we were getting them on film when we did, we now realize was a great thing. It’s really nice that we went when we did.

Is there a particular scene that just really stands out in your minds?

VALERI: I really think the mural that was done about Holy Cross, which involves walking the children to school, is always a very powerful scene for me to watch because it happened later in the conflict, when people were really hoping things were settling down. When you see things play out in such a way where children are affected, it can be quite an emotional thing to see. So, that one stands out, but there are many that stand out. The Mona Lisa mural, where a gun barrel follows you like Mona Lisa’s eyes follow you, really is a strong, intimidating image. We were moved by a lot of the murals.

What was it like to film over there? Did you encounter any obstacles or resistance, from one side or the other?

VALERI: Yes, we did, actually. We had to go back more than once because we really needed to build some trust for our interviews with the muralists, especially. Rightly so, they didn’t feel that they had ever been portrayed in a balanced way, or that their voices were every really heard. We felt so good, after we completed and were able to show the film to the artists, on both sides, and have them say, “Wow, thank you! This is the first time we’ve ever seen anything done, in a way that’s balanced.” So, we feel like we were able to earn their trust, and that they feel good about what we did. But, we did first encounter some fear and some resistance, and people not wanting to talk. There were some shots that went off in areas where we weren’t welcome, and we got the message and left. So, it was a building of trust, over time.

VINCE: David Ervine was very interesting guy, who was really a big catalyst for our peace process. He grew up in paramilitary groups, on the Protestant side, and went to prison. He ultimately had a mission in life to get rid of the sectarianism. He was a very important person for us. I really was impressed with him, just as a person for the journey that he had taken, from where he started to what his point of view was. He was very important for us, as far as reaching out. The Catholic side is more inclined to talk. They feel that their side has been a little more understood. The Protestant side is more reluctant and afraid of media. So, David was very instrumental in getting some of the muralists and the people to come talk to us and express their point of view about how they felt the conflict was concerned. He was very instrumental to us being able to take the journey that we wanted to take, letting all sides express themselves. I found him to be a very interesting and remarkable man.

VALERI: He was definitely ahead of his time. He was a very progressive thinker, who early on was thinking of ways towards peace and coming together, and because of that, he was trusted. He’s one of the rare people who had some respect from people on both sides of the conflicts.

VINCE: There are a lot of people, on all sides, that show respect to him.

How are the murals viewed within the community?

VINCE: I don’t know if there’s one answer to that. I think that sometimes they would be really proud. It was dependent on what phase that conflict was at, and what was going on. The one thing I’ve come to understand is that these paramilitary groups can’t really exist without the support of the community. They have to have a community behind them and wanting them. There are probably still factions, on both sides, that would want to return to that, but the majority of the people probably aren’t with that, at this moment in time. But, there’s a real controversy now, where the murals coming down are concerned. There’s not a unanimous decision there. What’s happening is that there’s an arts council that’s insisting on it. The artists are torn because, on one hand, the art was always just a reflection of what was going on in the communities and there is a want to get past it, but that being said, they would prefer a more organic transition versus an imposed transition. Some people feel that it’s good that these things are going away. Some people feel like it’s not good. Some people feel that the communities, themselves, should be allowed to gradually transition into different murals, instead of having it mandated. There would have been times where a paramilitary group would have came up and said, “We’re going to put this on the side of your building,” and you would have been hard pressed, if you didn’t want it, to oppose them. Right now, it’s a transition period that they’re going through, and I think you have differing opinions over what would be the right way forward, as far as the murals are concerned.

VALERI: You have parents and people who don’t want their kids walking past gunman murals, on their way to school. So, you’re always going to have a controversy over what’s being painted. As far as the murals coming down and the arts council, we talked to our muralists, since we’ve filmed, and they say they have turned down the money from the arts council because they don’t want to be told what to paint. It’s also not really the same. The way they were painting murals was always from a voice of something the community wanted to say, or that came about organically. So, to be told, “Put this image up so that we can have peace,” is a little different than, “We’re having peace, therefore we’re going to reflect that in a mural.”

What are some of your favorite documentaries?

VINCE: Well, there have been so many good ones, to speak of, that I don’t know if I have a favorite. I like a lot of the stuff that’s been coming out. I liked America: Freedom to Fascism. I thought that was an interesting documentary.

VALERI: I saw a good one, called Devil’s Playground. But, I think the draw for documentaries is that they’re better than fiction, most of the time. You couldn’t write these stories. They’re always so much more evocative because they’re real. They’re always engaging for us, in that way.

VINCE: I like Fat, Sick & Nearly Dead, about the guy dealing with weight loss. You can find stuff that’s interesting, in different subject matters, and I always appreciate different points of view. Waiting for Superman was a very interesting documentary. I thought that was well done. It’s nice when people are passionate about something, and it’s always better when they let the subject tell the story, more so then when you can tell people are trying to get their own philosophy into it. I really appreciate it when people go and investigate something, in an authentic way, and you get an insight into something. I’ve always had a lot of respect for the medium. We did a documentary, years ago, when I took a bunch of stand-up comics out on the road. We went through America and documented the comics doing stuff, which was lighter than this one. I think documentaries are an interesting way to learn a little bit about what’s going on and get some insight into a subject.

Art of Conflict is available exclusively on Netflix on June 1st.