The magic of animation is hard to define, perhaps because it's so infinite in scope. While major animation studios like Disney, DreamWorks and Pixar dominate the genre landscape with mass appeal epics and family-friendly adventures, there's an entire other realm of animated delights in the annals of cinema where filmmakers unconcerned with marketability or four-quadrant appeal demonstrate the limitless potential of the medium when refined craftsmanship meets unfettered creativity.

The world of weird animation is vast and diverse, and why wouldn't it be in the medium that has provided, long before CGI, the means to visually articulate the most fantastical realms imaginable without the budget-breaking limitations of live-action filmmaking. As such, in curating a list of recommended alternative animated films, this is only a small selection of the wonders you can find, from the proud careers of filmmakers like Ralph Bashki and Bill Plympton to the dark corners of films like Watership Down and The Plague Dogs (both of which are just a little too emotionally devastating for my taste). This is by no means a catch-all list, but a collection of a few of my favorite examples of how animated films can play outside the rules to create new worlds and concepts, sometimes far beyond the pale, that stretch our concepts of storytelling and world-building to their most fantastical, free-spirited ends.

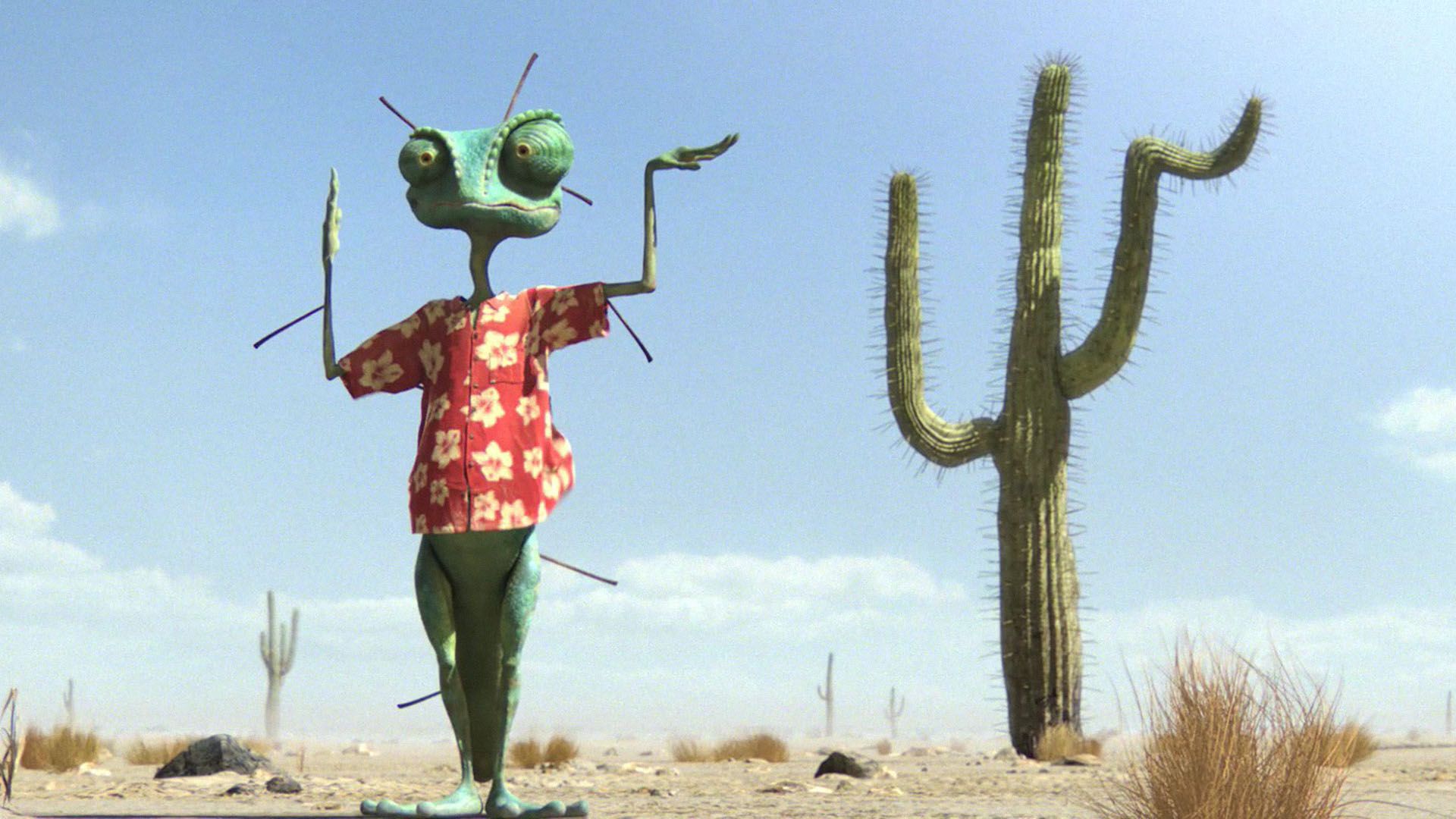

Rango

I owe Rango an apology. Despite the fact that Gore Verbinski is a solid filmmaker, despite the fact that ILM does some of the most exceptional CGI in the industry, and despite the talent of the voice cast involved, I dismissed Rango as boilerplate kiddy animation for years. I was very wrong. I'm sorry, Rango. However, that very disconnect is part of what makes Rango such a bizarre film. Marketed as your standard blockbuster animated fare, Rango was a studio-supported, massive-budget, wide-release "family film" that unabashedly plays to adults, boasts stunningly gorgeous animation, indulges in cinephile references, and straight up gets weird with it.

The first act is like something out my college avant-garde theater class. After a family-friendly prelude from a quartet of Mariachi owls, the film immediately transitions into a string of gibberish vocal warm-ups from out titular Iguana, Rango, as he sets the stage of his sheltered home in a bizarrely decorated terrarium -- most notable for the Samuel Beckett-esque landscape of a nude barbie doll bust, missing one arm and its head, centered on a mound of sand. As Rango boasts to and argues with himself (or a dead bug and a plastic palm tree), a literal bump in the road sends him flying into the wilderness. From there, we get a 15-minute stretch of pure surreality, as Rango (voiced by Johnny Depp) crosses paths with an animated version of Johnny Depp's Hunter S. Thompson and devolves into hallucinations. At a certain point, the Greek chorus of owls tells the audience (presumably children) "The lizard? He is going to die."

He doesn't, and the story eventually rounds out to much more conventional Western fare, as Rango become the sheriff of a dry desert town, overturns corruption and earns his place as the hero, but you can never quite ditch the sense that this film, with its barrage of sophisticated movie references and an ending that sees the mayor of said town dragged off to his death by giant snake, wasn't quite intended for the audience it was marketed to.

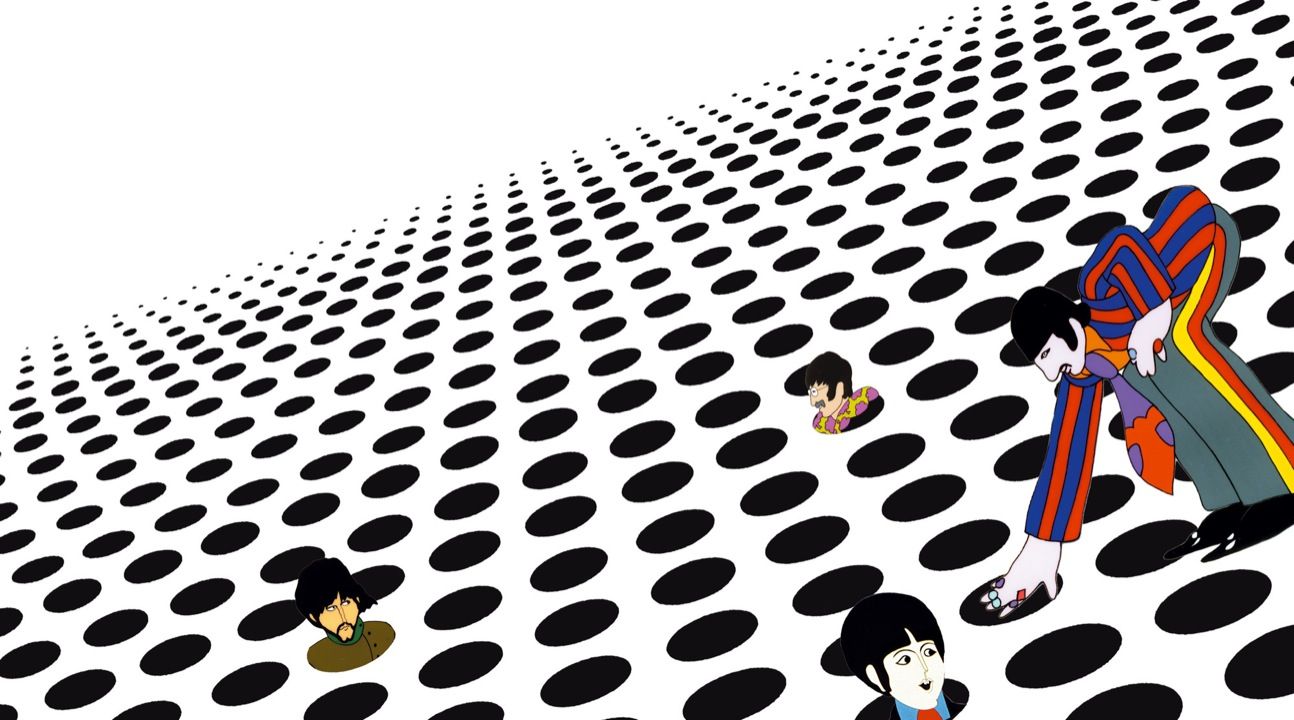

Yellow Submarine

Yellow Submarine feels like a lot of drugs. So, so much drugs. Released in 1968, Yellow Submarine is pure psychedelic pop art set to some of The Beatles' most catchy tunes, and obviously, that's delightful. Directed by Tom Halley and designed by Heinz Edelmann with an nearly unfaltering graphic loveliness, Yellow Submarine is flower-power grooviness at its most far-out. The plot is minimal, and minimally important, but basically it centers around a kingdom called Pepperdom that is invaded by the Blue Meanies – a giant race of very un-groovy buzzkills who can only be defeated by music. Enter The Beatles.

More important than the bare bones plot is Yellow Submarine's unwavering positivity and celebration of creative expression. A sort of rock-n-roll Alice in Wonderland, the film flirts with philosophy and cosmic ideas, but never gets dragged down in anything too deep, focusing instead on campy puns and one-liners and a relentless charge for love, peace, and the hippie way.

A Town Called Panic

If Wallace and Gromit and Toy Story dropped a ton of acid and made a baby, it would be something like A Town Called Panic. The French language stop-motion adventure from Directors Stéphane Aubier and Vincent Patar (who also provide voices) follows the antics of three plastic toy housemates – Horse, Cowboy, and Indian – as they encounter a mad scientist, explore a snowy wilderness, and discover an underwater lagoon near the core of the earth populated by duplicitous little sea creatures.

The basic plot, though I use that term loosely here, follows Cowboy and Indian when they realize they've forgotten to buy Horse a birthday gift and decide to build him a barbecue. An innocent error on their order form leaves them with 50 million bricks, far too many to handle and then...stuff happens. It doesn't make a ton of sense, and that's not really the point anyway. From the loose plot to the overlapping dialogue, there's a sort of anarchic frenzy to A Town Called Panic, as it scurries along with no particular place to go.

That free-wheeling abandon makes A Town Called Panic a somewhat baffling, disjointed watch, as if it were meant to be viewed in pieces, or however you like, really. And despite a lean 75-minute runtime, the film drags a bit at moments, but it's packed with so much surrealist humor and exuberant narrative nonchalance, A Town Called Panic captures the uninhibited creativity of childhood playtime.

Waking Life

One of Richard Linklater's two great mindfuck movies (along with his Philip K. Dick adaptation A Scanner Darkly), Waking Life is one of those movies that sends you out of the theater with a mind full of questions you're not sure any human being has the answer to. The film takes on the nature of consciousness, following the lucid-dreaming protagonist "Wiley" through a series of conversations and morphing realities with an unapologetic philosophical bent.

Visually, Waking Life stunning, the product of software developed by animator Bob Sabiston that transforms live-action footage (shot and edited by Linklater) into flowing brush-strokes of continually moving lines and shifting imagery. The result is a dreamscape of heightened, slippery reality where the lines between real and not-real become ever more obscure, or maybe just irrelevant, as the threads of existential questioning tug at your basic concepts of perception. It's visually striking with a relentlessly curious intellectualism, and while it may rely too heavily on dialogue for some tastes, it's a somewhat transformative viewing experience that sends you out the door in an invigorating state of creative contemplation.

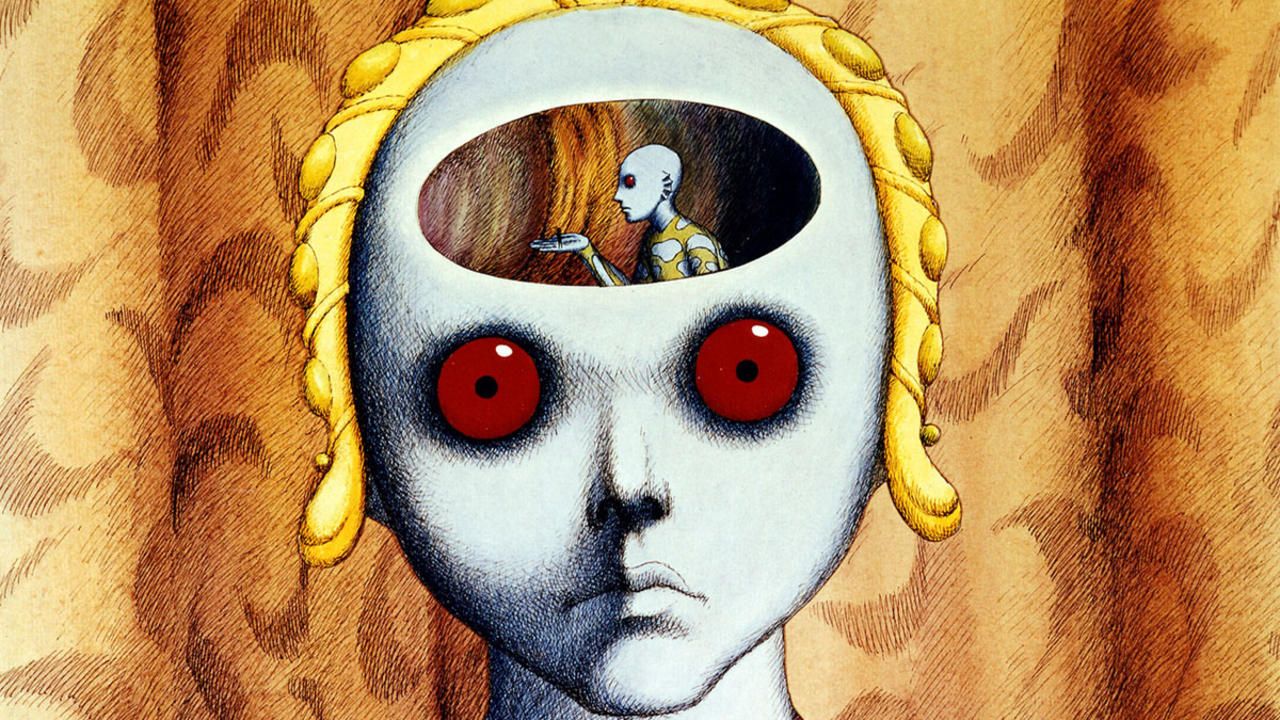

Fantastic Planet

This 1973 sci-fi directed by Rene Laloux from Roland Topor's stunning graphics is a fearlessly weird morality tale devoted to its aesthetics. Fantastic Planet tells of a giant alien race called Draags – blue-skinned and red-eyed, the Draags boast of a peaceful, elevated existence, devoting their entire lives to meditation, and yet their treatment of their subjugated race, the tiny human creatures called Oms (a spin on homme, the French word for man) is staggeringly cruel. Imagine if human beings were treated like rats – generally perceived as vermin to be exterminated, but occasionally taken as a pet – and you'll get a handle on how this supposedly enlightened race treats their human subordinates.

From the hallucinatory graphic animation to the pulsing, funky jazz soundtrack from Alain Goraguer, Fantastic Planet has a hypnagogic quality that drags you somewhere between dreams and lucidity with a pervasive unease. In the film's very first moments we see a ragged Om woman dragged, dropped, and flicked about by a trio of gigantic Draag children until she's nothing but a lifeless, broken heap on the ground, her infant son wailing in the background. It’s a startling introduction to the world that exemplifies the casual cruelty and cool logic that pervades this animated parable of racism, oppressed minorities and classism, even for all the extraordinary otherworldly animation.

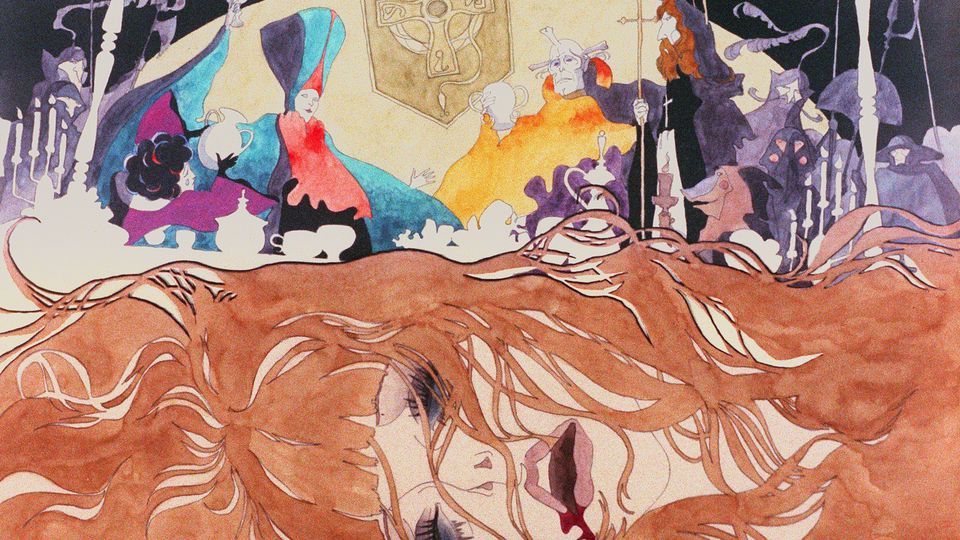

Belladonna of Sadness

Until very recently, Belladonna of Sadness was one of those infamous underground movies you could only find in blurry bootlegs, if you could find it at all. Fortunately Cinelicious Pics stepped in, devoted more than 1000 man hours to restoring the film, and now it's readily available to anyone who has a taste for some of the stunningly lyrical, abstract, and outrageous animation ever put on film.

The film, simply put, is insane. Filmmaker Eiichi Yamamoto's 1973 (very) adult-animation, based on Jules Michelet's 1862 history of witchcraft, is a stunning, grotesque portrait of corruption and the danger of female sexuality. While that last bit is a sticking point for modern viewers, there's no denying the prodigious artistry of Belladonna of Sadness, which plays like the most beautiful bad trip you've ever had.

The film follows two blissful peasants, Jean and Jeanne, on the eve of their marriage, whose love is disassembled when their cruel king lets his court rape the bride-to-be in a disturbing, stunningly rendered sequence of surreal imagery. It's only the first of many disturbing, deranged sexual sequences. In the midst of her dispair, Jeanne is visited by the devil, a small, slippery, and unmistakably phallic sprite that offers her unknown power. As she falls prey to (and grows more powerful from) the devil's influence, the film grows evermore transgressive, violent, and visually remarkable, falling somewhere between the lines of art and pornography – or maybe both at the same time.

It's Such a Beautiful Day

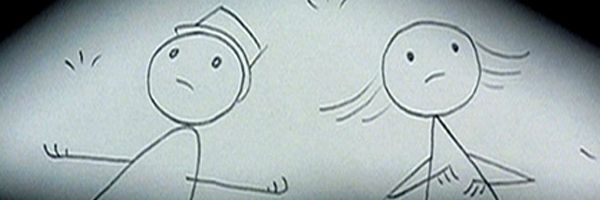

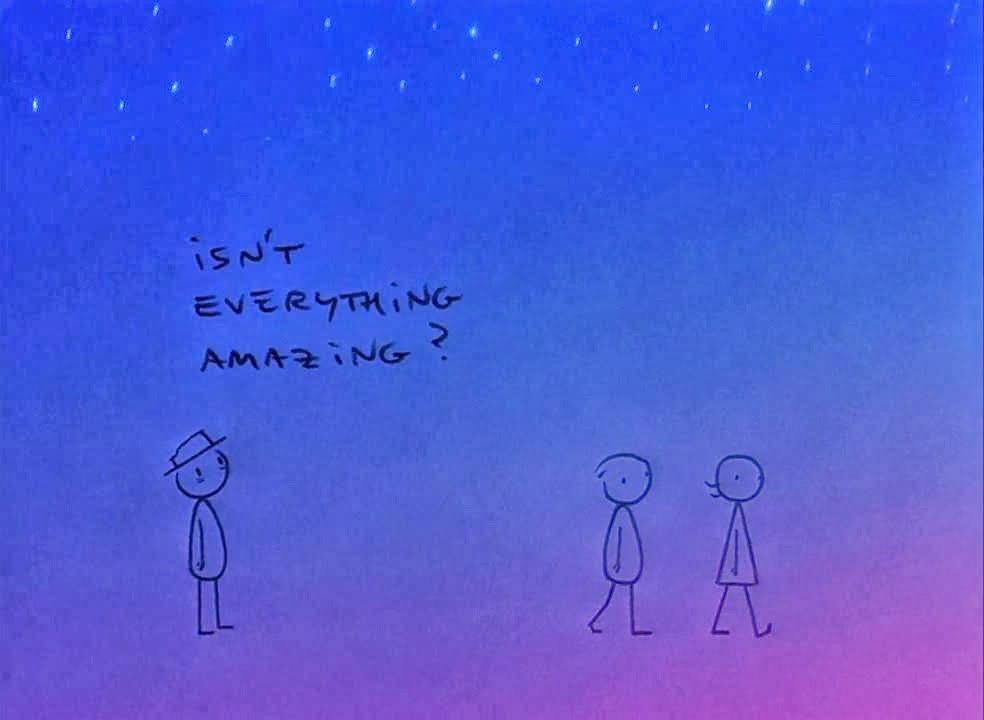

The path from Don Hertzfeldt's first Academy Award-nominated short film, Rejected (a goofy, if sort of genius collection of short cartoons chronicling the mental collapse of an animator through his rejected collection of corporate interstitial 'toons) to his most recent Oscar nominee, World of Tomorrow (a not at all goofy, if occasionally playful, meditation on youth, the desperate search for connection and what it means to be human, told through the construct of cloning), demonstrates how talented a filmmaker he is. But perhaps nothing else quite demonstrates his brilliance like his 2012 feature-length animated film, It's Such a Beautiful Day.

As always, Hertzfeldt presents his story through a deceptively bare-bones, stick figure animation technique that belies the complexity of both the story and the artistry committed to rendering it. It's Such a Beautiful Day puts you inside the mind of Bill, a man with a non-specific brain disorder, using in-camera effects and collages of experience to convey the gradual deterioration of a human mind.

The crippling, captivating thing about It's Such a Beautiful Day is the way it moves from moments of laugh-out-loud hilarity to desperate sadness, skipping only somewhat coherently from point to point in the narrative, Bill's eroding sense of reality ever-manifested in the fragmented, fluctuating animation styles. And while some of it may not make sense on first glance, it all adds up to a sum total that captures those inescapable, barely comprehensible truths of the human experience, in their full devastating effect.