Welcome to Marwen is a movie that inspires both love and hate. There are moments when it speaks to the healing power of art, creativity, and imagination in a real and profound way. And then there are other times when its gender politics are so toxic and backwards that you can’t help but cringe. The movie gleefully flips through genres, from war film to action movie to psychological drama, and it never wants to hold the audience’s hand. Robert Zemeckis’ new movie is kind of a disaster, but it’s a fascinating disaster because it takes some really big, ambitious swings that don’t always connect. Welcome to Marwen is a difficult movie to “like”, but it’s one that will always hold your attention even if it makes you want to scream.

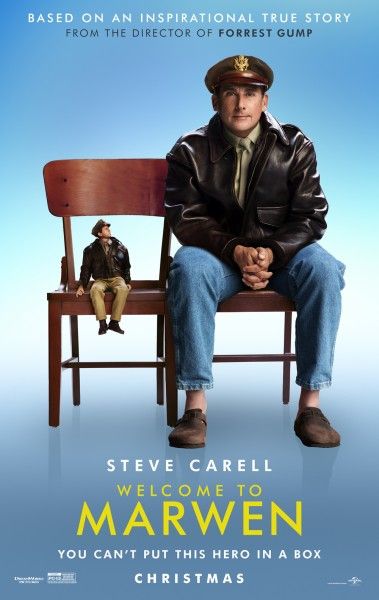

Based on the true story of artist Mark Hogancamp, the film flips between two worlds. In the real world, Mark (Steve Carell) is a photographer who was savagely beaten within an inch of his life by white supremacists outside of a bar when they discovered he liked to wear women’s shoes. Left without his memories and only the trauma of that night, Mark retreats into the world of Marwen, the other world of the story. In this world, rendered with motion-capture animation, Mark’s dolls, among which he is one, are in a World War II setting in Belgium. Mark is the only man in Marwen, but he’s protected by his friends, who are all women and all the female dolls have a real-life corresponding person. When Nicol (Leslie Mann) moves in across the street, Mark sees a chance of love and possibly salvation.

There are elements in Welcome to Marwen that are truly moving and positive, and, unsurprisingly, they tend to come from the documentary that inspired the movie, Marwencol. In this framing, Mark’s art is what heals him. Criminals may have stolen his memories and his ability to be an illustrator, but they couldn’t snuff out his creative spark and how he used these little dolls and the world of Marwen to help heal his broken psyche. It’s a powerful message about how art has a healing power not just for those who view it, but for those who create it.

The film is also incisive in how Mark’s refuge can become its own kind of prison. His art doesn’t move forward unless he moves it forward, so he gets caught in a loop, where a special doll, Deja Thoris (Diane Kruger), has dominion over him and all the characters. She’s a witch who can obliterate any chance of happiness of Mark’s doll, Hogie, and when paired with the Nazis who keep attacking Marwen, Hogancamp gets stuck in cycle. His art no longer becomes inspiring or healing, but a cocoon where he has complete control over everything and nothing can hurt him.

I admire the maturity of Welcome to Marwen see Mark’s art as a double-edged sword, one where it’s both his savior and his jailor, but where the movie starts running into problems is that Mark’s control extends to women. I don’t think Welcome to Marwen hates women as much as it dehumanizes them through reverence. It puts women up on a pedestal, but in doing so deprives them of their individualism and humanity. In Mark’s story, women are his saviors, but they also exist to serve his story. The women of Marwen don’t have individual lives or narratives. They’re all supporting players to Hogie.

Within the confines of a story about an artist trying to heal, you can kind of get away with this approach because it’s not our place to tell someone how to mend from trauma as long as that healing doesn’t harm other people. If Mark Hogancamp wants to dive into a fantasy world where all the women are sexy and they celebrate his machismo and don’t have inner lives, that’s fine. Fantasies are fantasies. But as part of a larger narrative, Welcome to Marwen does very little to question this approach. There’s a bit where we see the inner life of Nicol and what she’s suffered, but it feels like a large part of her story was left on the cutting room floor. Instead, Welcome to Marwen labors under the belief that because its female dolls are kicking ass and all the women in Mark’s life are trying to help him, it must be a celebration of women.

This is where Welcome to Marwen gets really icky because its views on women feel antiquated and myopic. There’s not much daylight between the women in the real world and the dolls of Marwen because both exist to serve Mark’s story. And Mark can be kind of a creep! Casting Steve Carell was essential because the innate gentleness and kindness he brings to his roles serves as a buffer in the truly cringeworthy moments like when he talks about collecting women’s shoes because it connects him to the essence of “dames”. It would honestly be less creepy if he just said, “Yeah, I have a shoe fetish,” which wouldn’t really be that big of a deal. But when you pair his obsession with shoes to how he directs the women of Marwen, Mark looks less like a guy who respects women and more like one who just wants to possess them.

The collision between the healing power of art and the fantasy of controlling women is what makes Welcome to Marwen such a fascinating disaster. And yet I’d much rather Zemeckis make this kind of movie that’s reaching for difficult ideas and tough themes rather than something fleeting like Flight or Allied. Welcome to Marwen shows that simply appraising a movie as “good” or “bad” as too limited a spectrum because there are elements that work beautifully and there are others that are a total fiasco. But I at least admire that there’s something worth discussing and worth considering in the mess Zemeckis has created.

Rating: C