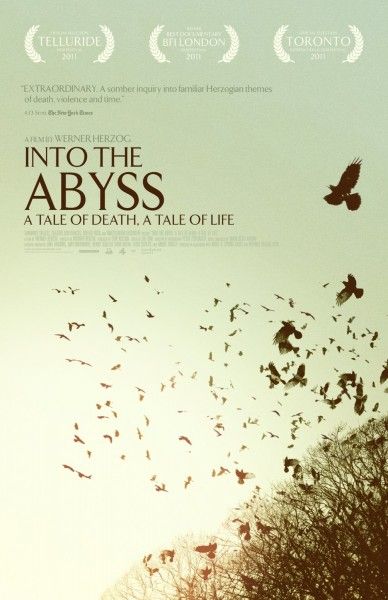

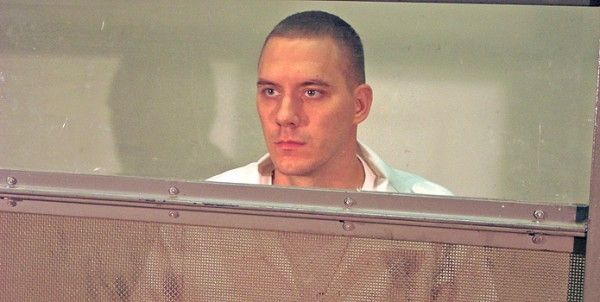

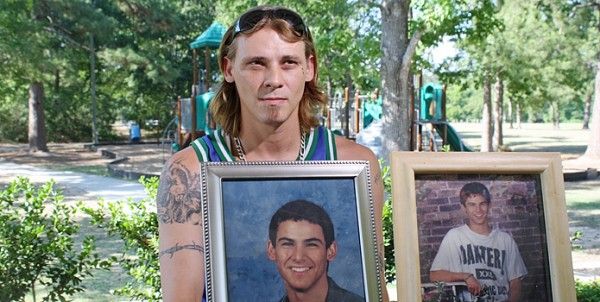

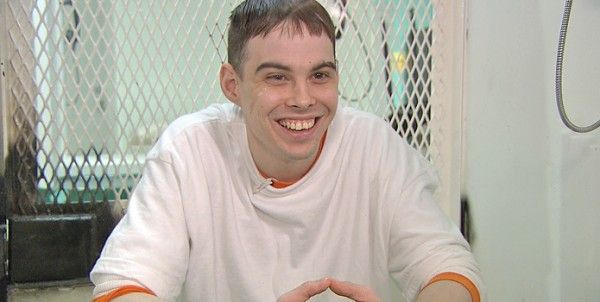

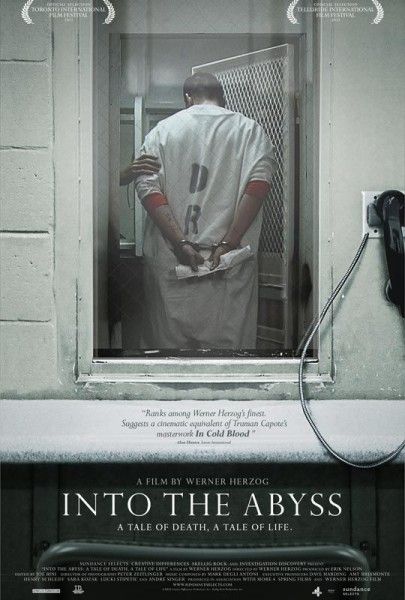

Master filmmaker Werner Herzog probes the human psyche to explore why people kill-and why a state kills in his fascinating exploration of a triple homicide case in Conroe, Texas. In intimate conversations with those involved, including 28-year-old death row inmate Michael Perry who is scheduled to be executed in eight days, as well as families of the victims, a pastor and a state executioner, Herzog achieves what he describes as "a gaze into the abyss of the human soul." His astute investigation unveils layers of humanity, making an enlightening trip out of ominous territory.

We sat down with Herzog at a roundtable interview to talk about what inspired him to make Into the Abyss and why he does not consider it an issue film about capital punishment but rather a sensitive examination of a senseless crime and all its ramifications. He described what it was like conversing with death row inmate Michael Perry and those affected by his crime, explained why he is not a proponent of capital punishment, and revealed how fascination and curiosity draw him to the subjects he chooses for his films. He also discussed what’s next including a four-part television documentary about inmates on death row entitled Death Row.

Can you talk about your decision to make this film and the two angles of the story that show both perspectives of death?

WERNER HERZOG: The choice for the subject was quickly established because I was so baffled by the senselessness of this crime. The two sides here apparently mean capital punishment, pro or con. It’s not a big issue. This is not an issue film. If you try to let your audiences believe that it’s an issue film, it would be disappointing for them. There’s very little debate about capital punishment in the film. But I’m not a proponent of it and I respectfully disagree with the practice. And, of course, as a German, I wouldn’t like to tell the American people how to handle their criminal justice.

Was it challenging to steer away from that?

HERZOG: No, I never steered into it. It was not the issue of the film. It’s not an issue film. It’s not a political film. It’s not a propaganda film. It’s not an activist film. It’s just about a senseless crime and all its ramifications including the death of one of the perpetrators and a triple homicide, the death of three human beings and all the repercussions and all the emptiness and all the wounds that this crime left in other people.

In most of your documentaries, you tend to interview people that you seem to admire like sports figures, scientists and people that you actually like. Was it different with this film?

HERZOG: No, I must say I liked them all with the exception of the perpetrators. I do not have to be chummy with them and I do not have to commiserate with them. Sometimes you see that these people on death row or in prison are made some sort of heroes, the outcasts against the rules of society. It’s none of that, and I tell Perry, who was executed 8 days later, that despite his bad early years this doesn’t exonerate him and it doesn’t necessarily mean that I have to like him. I respect him, and I tell him “I respect you as a human being.” I actually wore this suit here (referring to the suit he’s wearing for our interview) and I normally do not wear a suit, never visibly. It was just a sign. Yes, I respect you as a human being. People always tell you ah, they are monsters and just shoot them and they don’t see the value of proper due process. Yes, the crimes are monstrous but the perpetrators are still human. That’s how I see it. At least I respect them as human beings.

What did you learn in the process of making this documentary that you didn’t already know?

HERZOG: Nothing.

Nothing at all?

HERZOG: Well, in a way, yes, a few things. For example, I’m looking closely at the passage of time because for people on Death Row time sometimes comes to a standstill. Sometimes it accelerates. In this one case, Hank Skinner, who was due for execution tomorrow afternoon, got another stay. He was 23 minutes away from execution. You see death row is the Polunsky Unit in Livingston, but the Polunsky Unit doesn’t have a death house. They don’t have a death chamber so the inmates for execution are transported 43 miles to Huntsville, Walls Unit, where they are being executed. For 17 years, this inmate hadn’t seen much of the world at all and all of a sudden he’s in this van in a cage and heavily shackled and heavily guarded with armed guards around him and he sees a little bit of the world out there and he says “It was magnificent. It was all glorious.” I did this trip with my camera and all of a sudden an abandoned gas station and a cow in the field look like something glorious, like all of the glory of the world is there and it’s a forlorn area of Texas. He even says it felt like the Holy Land. All of a sudden I look at this bleak, forlorn Americana with the eyes of somebody who really sees the Holy Land. So yes, I have not learned anything but somehow my perspectives have shifted and that is big. But I do not make films to learn anything.

If you don’t necessarily set out to learn something when you’re making a documentary, then what is it that drives you or inspires you?

HERZOG: I think curiosity, trying to look deep inside of our human nature, look deep into the heart of men, and women, of course. Sometimes it’s the story itself that just jumps at you and you know this is it. For example, when Grizzly Man, the story, somehow stumbled into me, I immediately knew this is big. This is very, very big and I have to do it right away. I’m a storyteller and I work for an audience and I don’t want to just give them superficial things. I want to give some moments where for a short flickering moment you have the feeling that you have illuminated a person deep from inside and give you some sort of understanding of who we are. Those moments rarely happen but they do happen.

It’s not something that you set out to find? They just have to come up through the process?

HERZOG: Some things, of course, I’m setting out, like Antarctica, the whole continent (referring to his film Encounters at the End of the World). In this case, yes, I’m setting out because originally I wanted to go to Antarctica to film under the ice in the ocean. It’s like a science fiction world there. But I was not allowed to do that. Only the most expert divers are allowed, so I said I’d like to be in Antarctica, a part of being under the ice in the ocean. It happened and I tried to figure out a whole continent. It’s just fascination and curiosity.

How did you secure the cooperation of the families, the prison and the police who investigated the original crime?

HERZOG: I wrote to them and then I met them. Whatever you see on film is pretty much what I experienced with them. None of the people in the film I met with more than 60 minutes in my entire life – never before, never after. One exception would be Melissa Burkett, the pregnant wife of one of the perpetrators. She really wanted to know what she was getting into and she was hesitant to be in the film and wanted to meet me before and I had dinner with her in a restaurant. She took a good look at what I was all about and she agreed to be in the film. All the others…with the inmates, there’s a certain protocol. You have to write to them. Only if they write back inviting you, then you have to take the next step, and the warden has to agree. In one case, the warden, without giving me an explanation, refused. And you’d better also look into what the attorneys of the inmates are telling you. In one case, there was an attorney who sent me an email just a day before I set out for Texas and he said to me we have an ongoing appeal. My client may say something which might incriminate him or he may say something stupid, and if that is publicized, it could happen that his chances for an appeal are diminished. So, I immediately said this is cancelled. I’m not going to do it. I don’t care whether the person is guilty or not guilty. It’s not my business to establish guilt or innocence. It’s a court of law that does that and a jury does that, but not me. So I would immediately abstain from doing a conversation on camera.

Which do you think is worse, getting a death sentence or life imprisonment?

HERZOG: I posed this question to one of the family members of victims of violent crime. In this case, her mother and her brother were murdered and she felt a great relief when she witnessed the execution. I asked her cautiously would life in prison without possibility of parole, would that satisfy her. She said yes. I also questioned whether Jesus would have been an advocate of capital punishment. “Probably not” she says. But then, after a moment of hesitation, “But some people do not deserve to live.” So she’s vacillating and I opened the doors of the film [for her] to be herself and express her opinion. But it’s remarkable that a person who lost her mother and a brother contemplates seriously life in prison without parole. I rather tend towards that because I think a state should not have the capacity to kill off anyone for any reason. In Germany, you would be hanged if you cracked a joke about Hitler and you would be killed by the state if you were insane in a project of euthanasia. You would be killed, for example, for being Jewish or a Gypsy or gay – so 6 million. This whole culture of death hasn’t done good to the German people. It hasn’t done good to anyone. It’s articulated that way.

I heard the film was scheduled to be released in March and you decided it should be later.

HERZOG: No, I disagree because from April on I told the distributor we are going to be done with the film in June or July. They saw it in June. I immediately said we’ll probably be in Toronto at the festival. Let’s release it right afterwards so that we don’t get into the traffic of Christmas movies. You see, it’s a film that you’re not going to watch in the last ten days before Christmas. That’s why the distributors decided to release it in November which is a little bit late in my opinion, but as it is, the Christmas mood coming, they will widen the release at the end of January, February, March, something like that. But there was never a solid plan to show it later. I wished to show it maybe even in August or early September but I’m not a distributor and you see you shouldn’t overlook the fact it takes a lot of effort to find the right theater in the right city.

Did recent events influence the release date?

HERZOG: No, the recent events are events that nobody could foresee. For example, the execution of Troy Davis came at a time after I was long finished with my film. So it was a statistical coincidence and several other events like the Republican nomination for a presidential candidate. Of course, one of them, Perry, the governor of Texas, is very much into capital punishment. He represents the mood of his state. It’s obvious. And all of a sudden because of all these things, there’s a rekindled debate but it’s a complete coincidence because I think in June or so Perry was not even near announcing plans to run for the candidacy. Sometimes it happens that things come together as if planned but they were not planned.

As a filmmaker, you’ve gone from caves to grizzlies to death row. How do you go about choosing your subject matter?

HERZOG: I’ve never planned my career. I always follow what’s most urgently coming at me. It’s like burglars that invade your home, uninvited guests, and the one who’s coming most ferociously at you, you have to deal with that intruder first. So it’s all intruders who have come after me, and I mean big time. I have at least five, six or seven other intruders that are already lined up. I also run my own film school which I have to address. I do some acting and all sorts of stuff. But there I have more of a choice. I have a choice to establish my next rogue film. A seminar I do when I have an easy time to breathe and when I can sit back and I can look at all the applications. That’s easier. But film projects, they just keep coming.

Why did you choose not to show the lead up to Perry’s actual execution or to interview him or his family on that day?

HERZOG: You are not allowed. The family of Perry, there was only one left, because his father died only twelve or thirteen days prior to my conversation. His mother did not want to be on camera and made it very decently and clear so you stay back from it. You do not bother anyone in a situation like that, and of course, nobody films on death row. Even if I had been allowed and even if you handed me a huge amount of money, only over my dead body would I have done it.

You were very successful at getting people in this film to reveal their innermost thoughts and feelings while recalling very painful events in their lives. How did you approach them to draw that out?

HERZOG: It’s finding the right tone. For example, the woman who lost her mother and her brother, I think she immediately felt safe. She felt safe with me and she felt safe to speak. How I do that and how I can establish it I don’t know. But you see, part of me is not a filmmaker anymore but just a human being opposite of her or you. In a way, I managed to get the deepest things, the best things out of people. That’s why I’m a filmmaker. If you don’t have it in you, you’d better do something else.

Texas gets a bad rap because it has a lot of death penalty cases. Can you talk about your time in Texas?

HERZOG: May I interrupt you?

Yes?

HERZOG: I’m not in the business of Texas bashing. I really like Texas. But please go ahead.

I worked with the ACLU (American Civil Liberties Union) on the Innocence Project there and we worked on getting people off of death row. I was wondering what is your take on that?

HERZOG: You were trying to find cases where you were convinced that an innocent person was on death row. Is that correct?

Yes.

HERZOG: But when you look at Perry and Burkett, a court of law found them guilty, and if you look into the entire court transcripts and all the physical evidence and two confessions and one of the perpetrators and actually testimony of a person who was present during the murder of the two young men who is never mentioned in the film. It’s a long, separate story of a young woman who was in the woods while the two young teenage boys were murdered and she testified in court and she got immunity for it. But since the film is not in the business of establishing guilt or innocence, that’s all left out. But when you look at the entire case, summing up everything, you get the feeling that the jury found the right verdict. There was nothing where you could say this exonerates him or this points to his innocence – just simply nothing – although I allow both perpetrators at least briefly to maintain their innocence. But unlike other films which are trying to prove the innocence of an inmate, like Errol Morris’s film, The Thin Blue Line, yes, that’s a fine way to make movies but that was not the issue of my film.

Was this initially part of a mini-series?

HERZOG: No, not initially. No. That was immediately clear. Into the Abyss is a separate film for theatrical release and it’s feature length and it has to do with a big crime and part of it is about death row. Only one person is on death row. But, of course, there is a death row project which is purely television and I’m still working on it. I call it a mini-series in quotes. It’s four films which are here in the States, 44 minutes long each, but it’s a full hour on television.

What made this film compelling for feature treatment as opposed to being a part of that series?

HERZOG: In the small series of films, it’s more individuals on death row and most of the focus is on them. They’re not finished yet. I mean, I shot them all and I’ve edited three of the four films and I’m in the middle of editing, but there’s no mixing yet, no final form, no color correction, so it will take a little until these films are finished and they’re purely meant for television. They will be good. You see a lot of crime TV and stupid reenactments. There’s a lot of cheap television, but I try to put it on a different level.

You said you were a storyteller which I think sets you apart from a documentarian. From an audience perspective, this film is so much more powerful because it’s not an issue film. Is that something that you considered?

HERZOG: There are some issue films that are very powerful but I’m not into that business in this film. Yeah, it’s something really for audiences. It’s really for theatrical release. It’s not for me in learning something as you have asked. Yes. That’s never been the issue. I’m not important. What is important is what an audience sees on the screen. So, whether I had particular experiences and whether I learned something, it really doesn’t count.

Are you conscious of that storytelling being more powerful or is that just your style?

HERZOG: No, I don’t know. It’s just the kind of films I do best and I know what I should not do, for example. I wouldn’t be good, for example, doing Terminator. There are real good colleagues of mine who do it much better than I would ever be able to do it. I know what I do right and what I’m good at and I’d better stick to it.

Are you more interested in documentaries than dramatic fiction films?

HERZOG: No. It’s just quite often a chain of coincidences and quite often I have four or five feature films that I’d like to do but they’re not financed yet. If I had the finances, I’d start the next one tomorrow and the next one the day after tomorrow and so on. It comes as it comes. I like it all.

Other than the television project, is there anything else you’re working on now?

HERZOG: I’m preparing. I wrote a screenplay for a film and I’m planning to do a screenplay probably in the next fortnight or so, although I’m editing during the day. And there are quite a few other things out there. I never catch up in time.

Into the Abyss opens in theaters on November 11th.