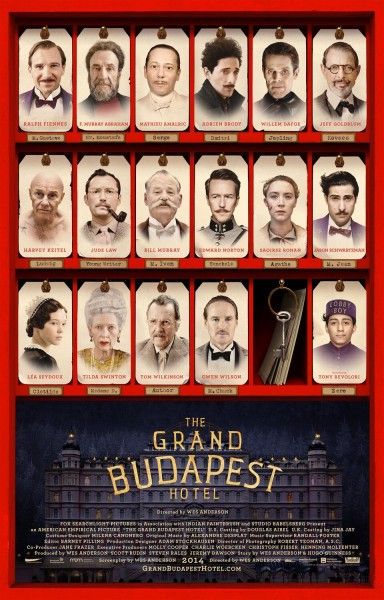

The Grand Budapest Hotel, Wes Anderson’s eighth feature film and one of his best, chronicles the bittersweet adventures of Gustave H (Ralph Fiennes), a legendary concierge at a famous European hotel in a fictional country between wars, and Zero Moustafa (Tony Revolori), the lobby boy who became his loyal and devoted friend. A timeless tale of friendship and honor as well as a kinetic caper in constant motion, the film features an impressive ensemble cast that includes F. Murray Abraham, Mathieu Amalric, Adrien Brody, Willem Dafoe, Jeff Goldblum, Jude Law, Bill Murray, Edward Norton, Saoirse Ronan, Jason Schartzman, Tilda Swinton, Tom Wilkinson and Owen Wilson.

At the film’s recent press day in Los Angeles, Wes Anderson and production designer Adam Stockhausen spoke about how the project first emerged, their collaboration on the vision for the film, how they created a lush cinematic world to invite the audience into, Viennese writer Stefan Zweig’s influence on the film’s multi-layered storytelling style, the selection of memorable books and films Anderson offered the cast during production and the sense of community he fostered on set, using different aspect ratios to tell each story within the larger tale, and one of their favorite scenes directing mobile haystacks. Check out the Grand Budapest Hotel interview after the jump.

QUESTION: Can you talk a little about how this project first came together and what inspired this particular story?

WES ANDERSON: Well first, it was just this character played by Ralph (Fiennes). And, it wasn’t a hotel concierge. It was just a guy which is inspired a bit by an old friend of mine and my friend, Hugo (Guinness), who wrote it with me. We had written a short story version of a script inspired by our friend, but we didn’t really know what to do with it or where it would go. It didn’t quite take off and it was short. And then, over the years, I started thinking that I would like to do something related to Stefan Zweig’s work. I started reading this writer who I’d never heard of and I just had this idea of doing something like his work. And then, Mike combined them and in the process of that had this idea of him being a hotel concierge. We always said our friend would be the greatest concierge and he said it. He said, “Oh I’d be wonderful. I’d actually be the very best.” We put that altogether and then we made the script very quickly. After that, we just needed the ingredients.

What was the thing from Stefan Zweig that you wanted to tell on screen? Was it the storytelling?

ANDERSON: It wasn’t one thing in the end. The first one I read was Beware of Pity and I immediately just loved the way we get into the story in that. It’s something he does over and over again in his fiction. In America, we didn’t really know Zweig until a few years ago. He was out of print except for some of the biographies maybe. I loved the way he began a story. I loved his voice and that book was just a favorite of mine. Then I read more of the fiction, and I kept seeing this device of somebody would meet somebody else in some settings. Sometimes they’re away from where they live and they meet some mysterious person, and then eventually some things happen, and that person says, “Well I could tell you my story if you wanted to hear it.” And that’s the thing. That’s the novel. That’s the story. But also, I read The World of Yesterday, his memoir which is kind of a portrait. The most memorable thing to me perhaps in it is his description of the Vienna before 1914 and the Europe before 1914, what it meant to him, what he thought he was participating in, and how suddenly and radically it changed and was just obliterated over the continuing years, first by nationalism and then these movements of fascism and socialism, and how they played out in front of him. His account of that became a kind of backdrop to me for what our story could be, even though our story really has nothing to do with it. The actual story in our movie is not really related to any Zweig story, but it’s that stuff.

You have an amazing cast in this film. How do you go about managing a cast of that size, especially with their schedules and everything else?

ANDERSON: Well, with the schedules, you’ve just got to figure it out. It’s a puzzle. I don’t remember anybody who we were really up against it with, like they were only giving us this amount of time and that sort of thing, so it worked out fine. Mostly, people who are going to come, who are well known and have agreed to do a littler part, they just want to know you’re trying to make it. You’re looking after them and trying to get them done in as reasonable a timeframe as you can and so on. With this kind of group, it’s not really a big thing of managing them. They’re all people where you bring them together and say, “Please do what you do.” They’re so authoritative and they all have so much of their own processes. We do all kinds of preparation, get everything set, and then they come in and it’s becomes a little chaotic. We work very, very quickly and they just sort of take over.

I love the worlds that you create in all of your films, but especially in this, it’s kind of a culmination. How did you go about collaborating together to create such a rich, lush world?

ADAM STOCKHAUSEN: It starts with research and with location scouting, and things are pulled from the real world from places that we see, even places we don’t end up shooting. There are always tons of details and amazing things that you see just traveling around and looking at stuff. And so, that’s kind of half of it. And then, in this case, I think historical research of hotels and of travel and of all these different things. And then, you take that and Wes thumbnails through the key sequences to begin, and then, more and more and more of the piece as we go. And then, you lay that all out on a gigantic table and start breaking apart what’s a set, what’s a location, what’s a miniature build, what’s a painting, what’s whatever, and work through step by step by step.

ANDERSON: He does a thing where he just gets millions of images and we start looking at them together, and I say, “I like this. I like this. I like this.” He’s great at gathering and shaping those. And then, each day, even in the earliest of phases of prepping everything, he’ll usually come to me at some point during the day and say, “Okay. Can we do 45 minutes at 3 o’clock?” We sit down and he says, “Okay. I’ve got this done.” He’s got things in different stages of preparation and different options of ways we can go and that sort of stuff. It goes like that over and over and over again.

STOCKHAUSEN: Yeah. It keeps going, because in the process of shooting, there’s new stuff coming every day, and you can’t possibly design all of it at one time at the beginning, so it’s really a rolling process. We’ll work all day shooting something, and then it’s like, “Great, but before we relax, we have to talk about what shoots next Wednesday, because we just got brand new sketches for that.” That process goes and goes and goes.

Was there anything that you brought to Adam and said, “Let’s do this” and Adam said, “No, I can’t make that happen” or that Adam brought to you where you’re like, “No, that’s not quite my vision”?

ANDERSON: No, because he didn’t really do that. I mean, I won’t say, “Do this impossible thing.” I might say, “Do this almost impossible thing.” But his response to “Do this almost impossible thing” is, “Okay. Let’s look at it and figure it out.” But essentially, he’s going to say, “We’ll do it. We’re going to make it work somehow.” Sometimes that means he’ll say to me, “Okay. I know that here’s what we want to do. If we do it on this day, we can do this. If we can shuffle something around and I can do it two days later, we’ll get the thing from such and such, and we’ll be able to do that and we’ll make a choice that way.” Often, it means we find some other approach because of something that’s going to cost this, and we think that’s not really so valuable to us. So anyway, it’s always changing. It’s always evolving. And this thing you were saying about traveling around and discovering things scouting, that’s a huge part of this thing if you just gather all this stuff and we want to share it.

STOCKHAUSEN: Because the real items just have their own stories. It’s so nice to have the real thing, not a cardboard version of it that we faked the real thing, but the actual thing.

ANDERSON: The actual real thing, and we’ll see these things and say, “Now why do we keep seeing this? In this part of the world, we keep seeing this happen.” I’ll say, “Well, these things over the doors mean this.” There’s history in all this stuff.

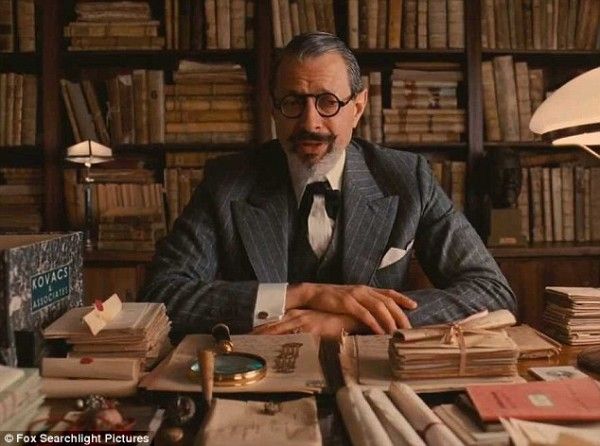

Jeff Goldblum mentioned you made other films and books available to the actors while they were on set. As vibrant as your script is and the set designs and this world that you created, what did you hope that they would take from those other sources?

ANDERSON: Nothing in particular. It’s just that everybody is there together and I’ve got all this stuff that I’ve been looking at. Now they want to just work on their thing and they’ve all got their own process, so I think it’s just for fun. And then, maybe they’ll use it one way or another. I don’t know what they do. It’s just, “Here’s the stuff that relates to the movie that we’ve got if you’re interested.” And literally, it’s sitting on a table there and people come by and take a movie. Sometimes maybe they’ll just like that movie. When you finish work, practically everybody in that place is going to watch a movie at night anyway. They’re tired. They have dinner. They go up to their room. They’re watching TV.

Do you remember what specifically you left for them?

ANDERSON: Yeah, we had one called Love Me Tonight. That’s a Rouben Mamoulian [movie]. We had lots of Ernst Lubitsch movies: The Shop Around the Corner, Trouble in Paradise, To Be or Not to Be, Design for Living, all the Lubitsch musicals. We had lots of ‘30s Hitchcock movies: The Lady Vanishes, The 39 Steps, and also Sabotage and Young and Innocent, and the Max Ophuls movies: The Earrings of Madame de and La Ronde, maybe we had that. We had Ingmar Bergman’s The Silence because it’s set in a hotel in a made up Eastern European country and a train and all that sort of stuff. In fact, we made their hotel corridors. His are in black and white so we had to guess.

STOCKHAUSEN: They’re very similar. All the hotel details are taken from that.

ANDERSON: Yeah, we just took them from his movie.

How do you bring your audiences into your films? In The Royal Tenenbaums, you have someone narrating the book. Rushmore has you opening the curtains and then stepping in. In this film, you have multiple layers: a girl with the book, and then that goes to the author (Tom Wilkinson) reading the book, and then going to F. Murray Abraham who is narrating his own story. Was there anything to bringing more into the different layers that you had in approaching this?

ANDERSON: Did you ever read Roald Dahl’s The Wonderful Story of Henry Suger? It’s one of the children’s books but for older children, I guess. That one has a very similar thing: a layer, another layer, another layer. There’s a guy who’s in a house, and he finds a book and he opens the book, and in the book, a guy describes what happened to him, and he meets somebody who then tells him a story, so it really does have all those layers like that. And Zweig does this all through his work. I think there’s a mystery about it and there’s a feeling of setting a stage and giving some meaning and some context before you get into things happening in one thing after another. Also, somehow I feel like without me deliberately wanting to say one thing or another about it, it’s something about just storytelling as some kind of thematic whatever-it-is that’s in there.

It’s this clever meta-comment on storytelling and playing around with storytelling devices. A lot of people talk about “save the cat” moments in films, but you have a “kill the cat” moment that’s so funny.

ANDERSON: They do that to make you like a character.

Here you have it where you really don’t like the character. There’s a visceral reaction to it.

ANDERSON: Is that right when people kill a cat like that? I was thinking of it in Berlin, and I said, “Why do you kill animals?” and these people said, “Well we don’t kill animals. These are actors.” We feel like what actor doesn’t want a death scene anyway? If I was a cat, I would say, “I would love it if you kill me in this one.” I have a great way I’m going to do this. So, I feel like I’m doing a favor to these animals.

On the set, you had this great communal atmosphere. Is that something that was particular to this film or is that in all of your films where you bring the cast members together and you all eat together? Does that help the shooting process?

ANDERSON: I don’t know, but it’s definitely this one more than any of the other ones, we were all together. Adam and Bob Yeoman, our Director of Photography, and Milena (Canonero), our Costumer Designer, and the whole cast, we were all together in one little hotel that we took over, and we had a cook that we brought in. It was a very comfortable, modest, but just terrific little hotel. In fact, the guy who owned the hotel and his wife, we cast them both in the movie. We cast him as one of the people in the front of house at the front desk of the hotel, and he was in a purple outfit and everything. We would leave work and then we would go back to the hotel, and he would already be there in his regular clothes. I don’t know how he always got there ahead of us, but we’d leave him at one hotel and he’d be waiting at the other hotel. I just think it’s more fun to have everybody together. Also, what I don’t really like is I’ve had this thing where everybody has trailers and nine different people are leaving, and they go watch ESPN or something like that, and we need them back on the set, and then one of them says, “Has so and so come back on the set? Well let me know when he’s on his way and then I’ll come.” You’re just wasting time. I feel like everybody can go home when we’re finished with the whole movie, but until then it’s nice if everybody just stays together and stays in it. I think most actors like that. Most actors want to kind of just commit themselves to it because it’s not a day job for most of these people. They would do it for nothing, and in fact, they have to if they work with us.

Adam, do you have a favorite set or location that you worked on for this film?

STOCKHAUSEN: There were tons and tons of really fun ones for this one. The hotel is obvious, and it was a lot of fun, but there were some little ones that were a lot of fun. One of my favorite stories from this one is this scene where they’re in a telephone booth in the middle of this snow covered field, and we have these mobile haystacks that you could get inside and walk around. One of my favorite days of shooting it was the day we were marching the haystacks around the field trying to line them up just right.

ANDERSON: We were talking with them on walkie talkie. There were seven guys inside the haystack and we’re saying, “Go to the right” and the haystack just moved left.

Were there any particular challenges to playing with the different aspect ratios?

ANDERSON: The only real challenge was from lawyers who just don’t know. Aspect ratio for whatever reason is a thing that goes into contracts. You’re required to deliver a movie between 90 minutes and 120 minutes in the 1:85 or 2:35 ratio. And so, the lawyers see this thing. We’re going to do it in a bunch of different things here, and they were like, “What is this?” and they think it’s a problem. For us, after we paid these fees for it to be argued over for a certain period of time, we then just did it, and it’s simple enough to accomplish. This sort of square ratio that most of the movie is in, every movie is shot that way essentially. Every movie except for a super widescreen movie is shot this way and then cropped. The negative is this. It’s just using a whole negative, and that’s the way all movies were like up until 1954, I think. And the other formats we’re using are just normal formats. We just shot them each like a different movie, and then it all gets put together. All the prints, almost everything, are done digitally now, so it’s very simple for us to decide how we want to present it. It was a very smooth process.

What are you working on next?

ANDERSON: Well, I just can’t say. I have this thing I’ve been working on, but it’s so early and I just feel like it’s … Because I’ve just been working on it, I’m kind of inclined that I shouldn’t say anything about that. It doesn’t sound good the way I described it and I could describe it better. I don’t want to put the bad version out there before I’ve had a chance to make a better one.