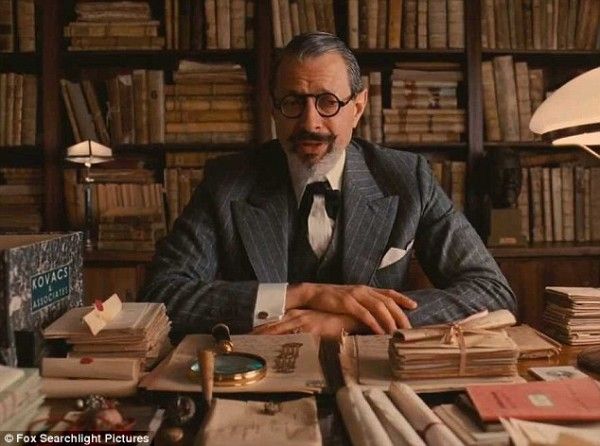

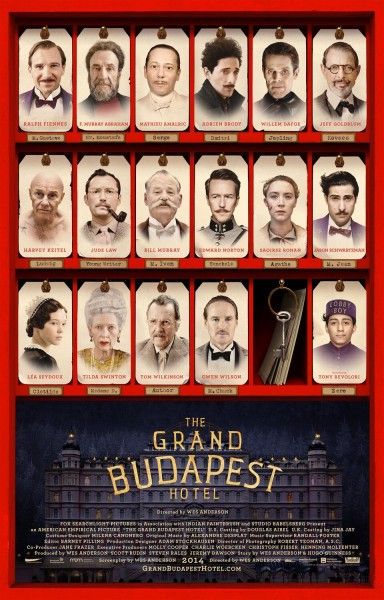

I love everything about Wes Anderson movies. From the way he creates unique worlds to the unusual characters that occupy the screen, Anderson is a one-of-a-kind filmmaker that always makes something special. His newest film, The Grand Budapest Hotel, just premiered at the Berlin Film Festival and it continues his streak of making exceptional films. The story mostly takes place in early 20th-century and revolves around the goings-on at a famous European hotel where a legendary concierge (Ralph Fiennes) mentors a young employee (Tony Revolori) against the backdrop of a changing continent. The film also stars Saoirse Ronan, Bill Murray, F. Murray Abraham, Edward Norton, Mathieu Amalric, Adrien Brody, Willem Dafoe, Lea Seydoux, Jeff Goldblum, Jason Schwarztman, Jude Law, Tilda Swinton, Harvey Keitel, Tom Wilkinson, and Owen Wilson. For more on the film, watch 13 minutes of behind-the-scenes footage and here’s all our previous coverage.

The day after the world premiere, I participated in a great roundtable interview with Anderson in Berlin. He talked about where the idea for Grand Budapest Hotel came from, the film's cast, choosing the locations for his films, his signature aesthetic, the various aspect ratios used in the film and his reasoning behind them, how budget has influenced or possibly changed any of his scripts, and so much more. It's a great interview so hit the jump for what he had to say. The Grand Budapest Hotel opens March 7th.

QUESTION: We were talking about your handling of heavy issues, historically and sociologically, etc, in a light manner. Can you talk about how you feel you balance these things?

WES ANDERSON: Yeah. I feel like actively, I didn’t. The story started out as – do you mind if this is sort of a long answer?

No.

ANDERSON: The story originally was inspired by this friend of mine – my friend Hugo, with whom I’ve been friends for years. He’s a painter, and he’s also very funny. I’ve seen funny little things he’s written too. We had this idea to do a story about our friend, and we wrote maybe 15 pages of this story that was set in the present in England and France. And, it was a movie, but up until he steals the painting, without the kind of setup with Jude Law. Then, we didn’t know what would happen next, and we just never did anything. That was maybe 8 years ago. Then, I had been reading these Stefan Sweig books – I’d never heard of them before – I really loved them. From the first page of one of these books I read – Beware of Pity was the first one I read – and I started thinking, I’d like to do something like that. I wanted to do a Sweig-esque thing. I was reading some other things at the same time that were getting into equally dark moments in Europe, and I had an idea to mix these things together, and make him a hotel concierge, which was not related to the thing before. Anyway, we just combined that stuff, and I feel like, I never wanna censor myself. We’re in a made-up country, we’re making wars together, we’re mixing up nationalities, cultures and the like. And this kid is stateless, which is a big deal at the time, and I don’t know if he’s an Arab or a Jew, or a mixture of them. I don’t know what happens with them, because it seems to be a war that starts in 1932, which is not exactly lining up with anything. So, I figured that we’d make our story and experienced based on whatever I had been interested in reading, and we’ll just see what that adds up to. That’s a very long-winded answer.

Is it your intent to have an impact on the audience in terms of-

ANDERSON: Well, it’s a choice to make a movie that’s in that world. Even though it’s not exactly in that time and place, it is, and everybody knows what we’re referring to and drawing on, so that’s the thing I was thinking about during that time, just because what I was reading, and that sort of thing, and where I was living. Anyway, that’s my attempt to answer that.

I feel like location always plays a big part in your movies, like the submarine in The Life Aquatic of Steve Zissou and the train in The Darjeeling Limited, and in this case, the hotel. At what point is the location something you start thinking about, because you have these characters, so you have to start thinking about the locations you create for it?

ANDERSON: Well, with this movie, we made the script. Then, we went on this journey around Eastern Europe. We went to Vienna, and Budapest, and all around the Czech Republic. We spent a lot of time traveling in Germany, and a little bit of time in Poland. We were looking for where we were gonna shoot the movie, and I felt for various reasons, especially tax incentive, we were kind of feeling like it would end up being Germany anyway. But, we wanted to go all over the place, and we sort of found something everywhere. We collected all kinds of ideas, and a part of the story that wasn’t in the script. In the script, there was this hotel in the ‘30s that was in its heyday, and there was the ‘60s when it was in decline, on its last legs. After we came back, after this trip, it became communist, and just in the architecture, we put in a bit of history and ideology and regime.

So you don’t already have the location in mind when you’re writing the script?

ANDERSON: No. During the script, I was looking at some old photographs and things, and I had found one particular hotel that I liked, but it was nothing like that anymore, so it was more like an inspiration than a possible location.

You’ve worked with Robert D. Yeoman before. I was wondering, how has your aesthetic with him evolved, and what kind of aesthetic did you want to achieve with The Grand Budapest Hotel?

ANDERSON: Well, I don’t know how it’s evolved, but usually, we might have some rules that we would come up with for a certain movie we’re gonna do. In this one, we had these different shapes and formats that we were gonna work with. Sometimes, we try to just limit how much gear we’re gonna have, and how we’re gonna go about something. The last movie, we had these little kids walking around in the woods together, and I don’t wanna do that with 60 people, so we made a decision about the whole movie based on that kind of situation. We even made a choice based on how tall these people were. There are these French, handheld 16 mm cameras that – you don’t put them on your shoulder, you hold them like this – and it’s just a better way to film someone like that. You’re gonna do a lot of handheld stuff with these guys. And that sort of affected the whole movie. So anyway, I’m rambling.

Is there anything you can’t do that you’ve come up with?

ANDERSON: Well, I’ll tell you one thing. Bob [D. Yeoman] is a great guy. We’ve done a million movies, every movie I’ve done with him, but, I’ve done a lot of other stuff with Directors of Photography who were great, like Darius Khondji. I’ve done some stuff with Darius Khondji. I’ve worked with Bruno Delbonnel. Am I saying his last name right?

I think so.

ANDERSON: And I’ve worked with some other guys. Bob is by far the best operator of everybody that I’ve come across. He’s 63 years old or something now, but he’s still the best at that for me, just in the physicality of operating, which he’s great with.

Do you think that this was, or were you aiming for this to be your most ambitious work to date? Because, the script is dense, the scope is so big, and it’s a story within a story within a story. Do you feel like you were trying to raise the bar quite a bit?

ANDERSON: I can’t say I thought about that. I think I knew it was gonna be a big undertaking at a certain point. Somewhere along the way, I started thinking this is gonna be hard. Like we were talking about before, there’s just a historical element to it. There’s something heavy that’s there that I was aware of, and I’ve never had a movie where there’s this much blood.

You’ve created a lot of imaginary worlds. There’s the imaginary New York in The Royal Tenenbaums, the imaginary world in this film, and The Life Aquatic seems to have its own imaginary species. What draws you to that, rather than doing New York at a specific time period, for example?

ANDERSON: Yeah. In a way, it’s just about making a space to work in. The real answer is just because I like to. On the one hand, usually the characters I’m writing are inspired, in one way or another, by people in real life, and doing something that relates to my own experience and my own interest. Nevertheless, I feel like the dialogue and the writing ends up being not entirely naturalistic, not by my choice particularly. Somehow, I feel like it needs its own world to exist in. And then, I’ve worked with a whole group of people for years, and that’s what we like to do: to make that place for these characters to do their thing.

Did you ever wanna be an inventor or something when you were younger?

ANDERSON: I wanted to be an architect.

I guess that’s sort of the same thing. It makes sense.

ANDERSON: Could I throw in one thing that relates to that question, by the way?

Sure.

ANDERSON: In a way, the reason there is a certain amount of blood in this movie, that might be the answer in a weird way, if that makes any sense.

In that first scene with the girl in the cemetery, there’s that building with the window, that’s very clearly an eye. Where is that place? How did that come about?

ANDERSON: Well, that’s a thing in that part of the world or this part of the world, really. But especially to the east, there’s a German word for it.

That type of window?

ANDERSON: Yeah, they’re called sleepy eyes, or something like that. You see three of them on a rooftop, or something like that. But, that’s part of traveling around before the movie. We saw a million things. In fact, that show is like a composite of different places we like that are made into one. But that’s very interesting. It’s a strikingly weird thing. It really feels like fairy tale stuff when you first see these things, driving around in Poland or something, and seeing a house basically looking at you. It’s very strange.

The aspect ratio is one of my favorite things in this film. I love that you made the decision, that when you go from 1.85 to 1.37, that the height spans-

ANDERSON: 1.37 might be the exact number. That’s pretty good. 1.33 is what I always thought it was, but then the German camera guys are very precise. You have to stop saying that (laughter). I was always told 1.33, but it’s not, apparently. It’s a tiny bit wider, I guess.

It was almost like watching IMAX on the screen today.

ANDERSON: That’s great. Why did you see IMAX?

It had a hugeness to it.

ANDERSON: But, did you see it in IMAX?

We saw it at the cinemax theater.

ANDERSON: Oh, but it felt like IMAX?

Is there gonna be an IMAX version of this film (laughter)?

ANDERSON: I was thinking about IMAX. Depending on where you sit, the movie’s here, and it’s also down there (laughter), which is pretty amazing. What I didn’t wanna do in this movie is have the movie suddenly get smaller. As a result of that, I don’t know if you noticed, but at the beginning of the movie, there’s black on all sides. We made the beginning little, so that it’s the first time you use the top and bottom of the frame, and it goes to 1.33. We never would’ve been able to do that a few years ago, because even when we did Bottle Rocket a few years ago, part of the conversation that we had was maybe we could do it in this way. But, with the movie theaters and the projection, you couldn’t do it in the theaters. Now, you just say you’re gonna do it, and you do it.

When I saw the film yesterday there was a slight issue with the projection. The masking happened very quickly. It was no biggie.

ANDERSON: I’ll tell you something. You know how at the beginning of The Last Waltz, there’s this thing that says “play the movie loud,” or something like that? We made a little card that says, “projectionists, please set to 1.85.” We did it with different colors and stuff. I’m trying to sell this stuff to everybody. This is not just for the projectionists. It was a real last minute thing and we haven’t gotten another. We should probably do it. We haven’t gotten it in there. Now we were talking about just doing it for a home video saying to do it, because this could be confusing. People could start messing around with the thing, and you’ve messed up the whole movie. So yeah, okay, good. That’s a good note.

The average projection in a plex today-

ANDERSON: Is there one?

It’s kids that are doing the candy stand. So, I just hope there’s some kind of control, because the potential is terrible.

ANDERSON: For confusion.

What was your inspiration for changing ratios during the movie?

ANDERSON: It was, at first, just to do it all academy. And then, I thought, how are we gonna do it? Are we gonna do some of it in black and white? What choices are we gonna make to separate this time period from that time period? The thing we did with Dara is we used these technical anamorphic lenses, that were really old and strange. If you look at a freeze frame of these shots, the edges are so blurry, you couldn’t identify people and things. I think they did like spaghetti westerns with these things. So, I thought, maybe we could use these lenses again, and we could make them different parts, like they’re different movies. I also thought, we’re so used to seeing these shapes bounce around like this, and we see things letterboxed, in whatever it’s called when you letterbox the sides. We’re just used to it. But I will say, when you sign a contract to do a movie, it says you are obligated to turn this in. When a team of lawyers sees this little rewrite we put into the contract here, it stirs up a lot of trouble. The legal fees – just to agree that we’re gonna do this – they mounted.

But it fits thematically. The nostalgia of the movie kind of fits the nostalgia of the formats.

ANDERSON: Yeah. I always have loved this academy shape, and it does remind me of old movies, even though ours is a color movie, and it’s Ralph Fiennes. It’s just the fact that you have these shots where we’re framed here. You’re used to this, and suddenly you’re seeing this. It’s how I see someone like Humphrey Bogart.

There’s certain themes that seem to tie your work together. I was wondering, when you sit down to write, do you have a certain theme in mind, or is that just like an afterthought?

ANDERSON: It’s a never-thought, really (laughter). I don’t really wanna think about themes. I wanna just think about the experience of the movie. I feel like, as soon as I reduce it to a theme, once I write that sentence, it won’t be that great. I feel like there’s more potential for it to mean something interesting if I’m not forcing it to mean something I’ve already decided.

There are so many great themes in this like, man out of time, man in an era, nostalgia for an era or a golden age – is that not conscious, or is it personal? Are you romanticizing certain periods? There’s so much good thematic material and texture.

ANDERSON: I think it’s just, what I’m interested in is what I wanna put in there. I’ve spent as much time as it takes to do one of these things. It’s only gonna be the ideas that myself and my collaborators can come up with together. I don’t wanna make it something that isn’t digging into things. I just don’t wanna identify them.

Are you romantic for those past eras, or that time period?

ANDERSON: The Library of Congress has this thing called photo chrome library. I’m not sure if we put that in the press notes or not. It’s this collection of black and white photographs that this Swiss company and maybe St. Louis, I think these two companies did a joint venture. They had photographers take cityscapes and landscape photographs all over the world. And they colorized them, printed them, and mass-produced them. They sold them, and they’re like these thin paper pieces with very beautiful views. Very rarely do they have people in them, and if they do, they’re usually crowds. They’re taken between 1895 and 1910, something like that. There are thousands of them, and they’re all over the world, but our interest was Austria-Hungarian empire and Prussia, and other parts of Europe. It’s like Google Earth access to the turn of the century. When we made Rushmore, years ago, when I was writing the script, I was thinking of places in my school where I’d gone. During this movie, because I was thinking of these things, the backdrop was through this collection, that we owned, that theoretically is ours. Often times, we went to most of these places. Many of them were just views of the time when people would go to just see this view, and so they’ve built a terrace, which is there for people to visit. You can’t go to too many of these places without feeling a little bit of sadness, because, there are just so many more people, and the world is not like this anymore. If you have any nostalgic bone in your body, that process could be rough, but I will say that that’s not my experience in life in general. I’ve been spending a lot of time in Europe in the last 10-15 years, and I like it because it’s an adventure to me. I just enjoy walking down a street I’ve never been down, because there’s so much history everywhere.

One of the big draws for this film is the posters, with a lot of Wes Anderson players, who have worked with you on multiple projects. You have a lot of small parts for a lot of these characters. Do you just email them or call them and say, “I might have a part for you. Come to Germany”? How do you actually approach getting everybody on board?

ANDERSON: For anybody who I can do that with, that’s what I did. I sent the script and the pitch, and I would attach some of these photo chromes. Most of them, I did directly. A few people, I didn’t. Ralph Fiennes and I had never worked together, but I knew him, and I knew how to reach him. I’m trying to think of who I didn’t reach directly. I didn’t reach Murray Abraham and Tom Wilkinson directly, but I think that, even now, I’d have to reach Tom Wilkinson through his agent. But, everybody else, I can get them directly.

We were talking earlier about that line that Murray delivers about a man being already out of his time. You get the sense of, how much of that do you feel is you? Are you that type of man?

ANDERSON: I don’t really, but there’s two things. One – the guy we based it on – I don’t know if he feels like that, but he is like that. By the time he was 15 years old, he was the kind of person he is in his 50s now. He’s one of those people who’s fully formed young. He’s always been friends with people who are 30 years older than him, and there’s something about him that’s like somebody who’s 85. He knows people who you should have really been older to have known, and thinks like that. The second thing is, it’s in Sweig, Stefan Sweig. His memoir is about how Europe changed, and how the world changed in the course of his whole life. But, the title of the book is The World of Yesterday, and there’s something about his description of life before 1914, that is, in a way, the thing that sticks with you most when you read it. To me, I’ve never quite read a description like this of that world. The end of that world is, that he writes his book and he kills himself. That’s the thing that he’s still missing, so, I related to that a bit.

How much do you relate to your characters? Are there a couple whose worldviews you connect to more so than others?

ANDERSON: I think there definitely are some characters like that, yeah. In Rushmore, it’s really like where I went to school. Owen [Wilson] and I used our own specific experiences that went into it. Most of the other ones are not like that, but they’re usually all just whatever I’m most interested in at that time. In that manner, they’re all personal, one way or another.

Bill Murray said that, the first day he shot with Jason Schwartzmann, he thought Jason really sucked. Then, the next day, he was awesome. Was it a similar experience finding Tony?

ANDERSON: I’m pretty sure that Bill has shaped this story a bit over the years (laughs). I recognize parts of it, and he did, but there was a process of him feeling comfortable with Jason. He also made that happen. Jason was acting a little wild, because he was with his hero. I’m not answering your question. I wanted to respond to those comments. After his first day, he invited us to go to a restaurant to have chicken fried steak, and the three of us had this night out together. Jason didn’t drink or anything. He must have just said, “I don’t feel good about all this, and I’m going to try to make it fine.” And then, he did. He’s a guy who can do that. Another guy, Seymour Cassel, the one who did the damage later, that was late in the game. That was one of those things where, you’re going along this movie in the company of 3 people, and everybody forgets that one of us is 16. You forgot that one of us, when all this movie is said and done, has homework. You forgot that, not only was he super young, but this was his first job before, so he was reacting to that. He seemed to kind of dramatize that about him one night towards the end of the shoot (laughs). But what was the actual question?

That was a great answer, but just speak to the parallel with Tony.

ANDERSON: The thing I learned when we did Rushmore is how long it can take to find some guy we’ve never heard of. We must have spent almost a year looking. So, in this one, as soon as we had the script, we gave it to Scott Rudin and Steven Rales, and said, if you like this, let’s hire 11 casting directors in these countries all over the world, and let’s get a guy to paint this portrait. I have these two guys who I’ve been working with for years, and luckily, they’re great. The next day, we started to make that happen. It was the same thing with Jason. We looked all over the world. We looked in England to try to cast someone. We looked at someone in Bel Air. In this case, we had a casting director in Israel, and Beirut, and in Morocco, and we cast somebody from Anaheim, but what can you do?

What did Mario have to do to get the part?

ANDERSON: I saw Mario’s audition first, and I thought, “interesting,” and we kind of pulled him off the desktop. Then, I saw the next one, and I knew Mario was never gonna get this part, because the next was Tony. But, I feel like Mario is a little bit connected to this movie anyway, because Tony and I did this thing where, leading up to the movie, I would make him do the whole movie on a video and send it to me. Then, I would do a video responding. Then, he would send one again to me, and we just went back and forth through the whole movie, and Mario was the person he did all the scenes with. He’s sort of connected to it, in a way.

I’m curious as to how budget has influenced or possibly changed any of your scripts along the way. For example, with this one, was there anything you guys scripted that you realized, “we’re never gonna have the money to do this”? And, I’m just curious about your other films in respect to that as well.

ANDERSON: It does, but I don’t think we end up saying, “we don’t have the money to do this,” because it feels like there’s no upside, or no way we can make ourselves feel good about doing that. But, we definitely end up saying, “we’re going to do this a very weird way,” because it’s the only way we’re going to manage to accommodate it. We have this skiing sequence in our movie, and in the script, and the first person looking at the budget might have thought it was 3 weeks of shooting in Switzerland. I had this vague idea that we could do the sort of snow globe version of this thing, and that that might be more interesting anyway. But, if we didn’t do it in this way that we did, we would’ve been pretty much up against it. I have no idea what way we would’ve gone about it. I feel like I have a rule where I try not to just give up on something that’s in the script, based on money.

From that, how did you make that scene?

ANDERSON: That is kind of complicated. For instance, for the bobsled run, we built a bobsled run that’s ultimately about the size of this room. And, we used kind of a combination of stop-motion and live action miniature techniques, plus a lot of digital manipulation. It’s really using like the most old-fashioned movie techniques with a lot of digital stuff to fuse them together, and modify the speeds, and all that kind of junk. Then, in these kinds of shots, we’ve planned them out and figured out what our strategy is gonna be, and we’ve got a thing that’s sloped down for the camera to move through. But, we’re constantly not getting it good enough yet, and having to do something else that involves shooting another physical element that we’re digitally putting in, or, we’re just manipulating it. It’s a very long, ongoing process. It’s pretty vague.

Were the actors even there?

ANDERSON: Ralph and Tony were there. Willem had some bits in the beginning, and I probably shouldn’t say this, because I don’t wanna be vague.

You don’t wanna reveal the magic trick?

ANDERSON: It’s not that I don’t wanna reveal the magic trick. It’s that, when I reveal the magic trick, there’s something slightly humiliating about it. But, Willem is mostly a stop-motion puppet who’s this tall. Maybe that’s obvious (laughter), but I’m still reluctant to say it out loud.

Thank you very much.

ANDERSON: Thanks so much, everybody.

For more on The Grand Budapest Hotel: