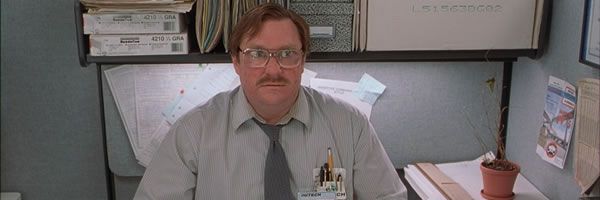

The core of Office Space is the absurdity of office life. Mike Judge’s comedy wasn’t the first to seize on this, and the second-half of the 20th century is filled with examples of people feeling like meaningless drones in a corporate existence that holds considerable sway over the lives of individuals while also divorcing individuals from their individuality. Peter (Ron Livingston) chooses to meet absurdity with absurdity, becoming disconnected from a workplace that has no connection to him. But through it all, Office Space has just that—space. It’s a workplace that’s both uncaring and unpredictable, but it also functions as a home station and place of security (until Milton (Stephen Root) burns the building down).

Twenty years later, offices haven’t gone anywhere, but our economy has drastically transformed. When Office Space was released, we were in the middle of the dot-com bubble, which didn’t burst until 2000, so Office Space is a story told in relative security. Peter’s job sucks, but he has a job. The question isn’t “Can we get work?” but “What is the quality of our work life?” The job is a given, and, being that it’s a 40-hour-per-week office job, Peter presumably has healthcare benefits and so forth. The film’s conflict and comedy comes from Peter rebelling against his workspace. But what happens when that workspace is no longer a given?

Office Space isn’t unrecognizable twenty years after its release, but we’re in a far different world. We’ve gone through the Great Recession and an economy transformed by the Internet in a way that was only beginning to surface in the late 90s. Initech, Peter’s company, would likely have been absorbed into a larger tech giant, and for the part of writer-director Judge, he’s gone on to explore that world in his HBO series Silicon Valley. But that show tends to explore the working world from the top down. We see it from the hustling creators of Pied Piper to the buffoons leading tech giants like “Hooli” (i.e. Google). Rarely do we see the lives of the working drones, and even if we did, it would be more specific to the Silicon Valley lifestyle.

What hasn’t really been explored is how the gig economy has transformed the lives of the modern worker. You have huge companies like Uber, AirBnB, and others technically letting the individual run their own hours, but it’s the crushing life of a freelancer who’s been abused by an indifferent system. Once again, you have the clash of the individual against the corporate life except the setting has left the office and moved into an individual’s home, car, and anything else they could possibly use for even the slightest profit while a tech giant reaps most of the rewards.

There’s definitely room here for the dark, absurd comedy that Office Space provided because while Judge’s follow-up film, Idiocracy, tends to be cited more and more, there are definitely lessons to be had from Office Space and its rebellion against a monolithic and random culture. In the world of Office Space, you can devote years of your life to a company, be laid off unceremoniously by people who don’t know you, try to commit suicide, decide against suicide at the last minute, and then get hit by a drunk driver, which results in serious injury but also a seven-figure settlement. The illusion of control that the office job—and really any job—provides, would fit nicely to the setting of the gig economy.

Of course, you can’t really call it “Office” Space without the office, and that’s okay. While the setting was obviously essential to the 1999 comedy, the larger story is one of workplace malaise and frustration. The inanity Joanna (Jennifer Aniston) has to suffer through is just as mind-numbing and ridiculous even though she works in the service industry and Peter works in information technology. The workplace is the problem, and I’d love to see a story that shows how that problem evolves when the workplace is your life rather than something you can leave at the office.