One of the main arguments for the so-called “superhero fatigue” is that superhero movies are becoming all too similar. The MCU has its “Marvel formula” which is rarely broken, and the “Arrowverse” too has a tendency to default to angst whenever possible, with the exception of Legends of Tomorrow being nearly indistinguishable from each other in terms of story and tone.

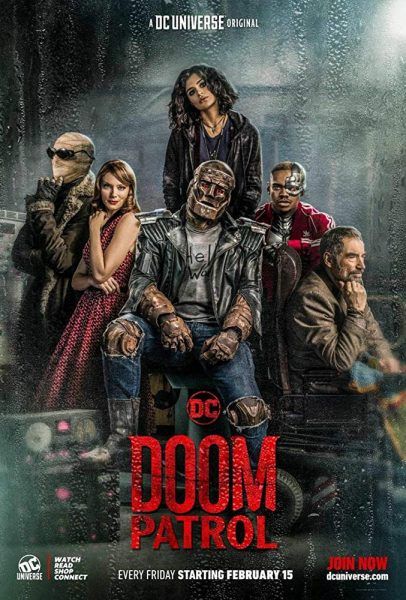

Of course, there’s exceptions to the rule. Guardians of the Galaxy provided a breath of fresh air to the MCU that paved the way for Thor: Ragnarok and Black Panther. On the DC side, Doom Patrol finally gave us a superhero show that isn’t afraid to go completely cuckoo bananas with its weird storylines and side characters, without losing sight of the emotional journey of its characters.

You’d be forgiven for thinking that Doom Patrol, and its tale of people whose powers and appearance alienated them from society and are more like a curse than a gift, sounds similar to Marvel’s X-Men. But to do that would be to diminish what makes Doom Patrol special.

At the heart of Doom Patrol is a rag-tag group of accident victims and marginalized outcasts whose powers are often manifestations of their traumas: Crazy Jane (Diane Guerrero) is a girl with 64 different personalities all with different powers, which were created as a defense mechanism to help survive her abuse. Rita Farr (April Bowlby) was broken by the Hollywood system of the ‘50s and now battles with keeping her blob-like body in one piece, which becomes a stand-in for her own self-loathing and body issues. Larry Trainor (Matt Bomer) and his self-hatred towards the Negative Spirit that resides within him is a not-so-subtle allegory for Larry’s internalized homophobia and regrets of the past.

Though Doom Patrol does get as dark and grim as Titans, it is often as ridiculously funny as Legends of Tomorrow. The first season is mostly a search-and-rescue mission, but in the way the team gets in the most bizarre situations ever seen in a superhero TV or even movie. What other show would wrap up a season with a giant cockroach with a god complex fighting against a giant vigilante rat who craves vengeance for the murder of its mother à la Batman? Beyond that, what other show would end that fight by having the rat yell, “I wanna spread you like the plague, Daddy.” Before resolving the fight with a make out session in the middle of a sentient, genderqueer street?

Where Legion gives us bizarre scenarios and plenty of WTF moments, they’re usually done in a disturbing way to show how fragmented David Haller’s mind is. Doom Patrol on the other hand gives us a man who can learn everything about a person by eating their beard hair or a flock of man-eating butts to make us laugh as the characters shout profanities in confusion, while never losing sight of how these situations affect the characters’ growth.

The first season of Doom Patrol deals with the team coming together and searching for their chief and father figure, Niles Caulder (Timothy Dalton), but that overarching narrative is often a secondary concern next to the emotional arcs of the characters. In the first episode alone, the show quickly gets the origin stories out of the way and gets right into the character development and the weird. Even in an episode where the characters enter a town inside a pocket dimension though a magic donkey, the main story is the Doom Patrol reliving the moment they got their abilities and facing their past mistakes and trauma.

What makes Doom Patrol special is the show’s ability to take a pause and let the moments breathe. Even if it seems like the plot is moving at full speed, it often stops to show how the many plot-twists affect each of our world-be heroes. Where other superhero shows feel the need to feature a new villain or crisis each and every episode, Doom Patrol can go from an incredible two-parter take on Infinity War and Endgame featuring a massive and omnipotent eye in the sky that turns its random victims into ash (turning an entire arc from the comics into merely a monster-of-the-week story) and then spend an entire hour in a group therapy session. While Arrow and Flash focus on the toll a superhero’s life takes on their personal life, and the MCU is just now beginning to explore trauma in their heroes, Doom Patrol has trauma and pathos and its core. Tony Stark may have used Bruce Banner as his unlicensed psychiatrist, but Robotman convinced the entire group to do a therapy session while having a rat mess around in his head.

At its core, this show is about how we can’t fully erase our trauma, but we can try and cope with it and eventually come to terms with our current situation. Every character is guilt-ridden in one way or another, and their journey is not really about controlling their powers or realizing their potential but finding the emotional support network they need to survive this world and slowly accepting that their new reality doesn’t dictate who they are. Like Endgame thought us, it is not about who being who we are meant to be, but simply who we are.

This is true of each member of the Doom Patrol. Take Larry Trainor, for instance. The former pilot now vessel for a being of negative energy if often the emotional center of the show, as his struggle to accept the being living inside him reflecting his decades of not accepting his sexuality and hiding from the world. Through the season, we see Larry starting to cut loose and starting to accept himself and the Negative Spirit, and even bring closure to a relationship left unresolved for half a century (I dare you to watch Larry’s reunion with John and not cry!) Though she didn’t spend that much time in the spotlight, Rita Farr’s story is equally as impactful. The famous actress from the Golden Age of Hollywood always lied to herself, presenting a version of herself to the world that was but a façade, and after a freak accident she now struggles with realizing just who she is and the mistakes she’s made.

It is fair to say the most surprising of the character journeys is that of Cliff Steele (Brendan Fraser), the former race car pilot who becomes just a brain in a robot body. Despite being mostly use for comic relief (and to rival Steve Martin’s F-word tirade in Planes, Trails & Automobiles), the show also explores his deep depression and anger issues that result from his regrets for being a bad father.

Still, this is a superhero show with a fourth wall-breaking narrator that once appeared with a DC hat and burn down a poster for the show he was on. Doom Patrol not only has excellent character development that extends to even its villain, but the biggest moments of growth usually come in the most bizarre episodes and scenes. Do a quick search on the show and the two things that will likely show up the most are the karaoke scene and the mass orgasm scene. Why yes, there is a scene where a superhero flexes a muscle and gives an entire street (including the actual street) an orgasm. Not only is that a hilarious scene, but it comes with the Doom Patrol realizing Cliff’s inner rage at not having sexual organs or a body.

The other is a scene in which Larry Trainor sings Kelly Clarkson’s “People Like Us” while at a cabaret inside the sentient genderqueer Danny the Street. It is a significant scene because Larry finally embraces what makes him difference and lets himself go and have a good time for once, singing a beautiful song of self-acceptance with a drag queen backing him up. It is a fun scene in and of itself, but it is what we learn of Larry that makes this an outstanding scene. Despite it being a dream sequence, for five minutes we realize that Larry always had the power to mend the two parts of his broken self and heal himself. When he sings, Larry sees himself as his former self, as whole, because he stops holding himself back. Sadly, when he sees an opportunity to finally be free, he gets scared and goes back to being his old, broken self.

Plenty of superhero shows or movies separate the action from the character development, usually dragging down the former to explore the latter, but not Doom Patrol. I dare any other show try and make its audience care this much about every minor character while also making them laugh at the sight of a man that’s part vegetable, part mineral, and part velociraptor. This is a rare experiment in TV storytelling where melancholy and pathos are the special of the day, and nothing is too crazy for the screen.