For anyone who wants to make a movie, there’s an undeniable appeal to the studio system from the Golden Age of Hollywood. It’s a handy thing, to have actors, directors, writers, designers, and technicians all under contract and ready for assignments. Working relationships can be maintained over a long span of time, shooting under such a system is (usually) efficient, and production values can reliably meet a baseline quality. With this working model, the major studios of the '30s and '40s developed their own recognizable “house styles” of filmmaking, whether it was the slick elegance of MGM or the staccato grit of Warner Brothers. And actors embedded in the studio system built up iconic screen personas that could make them international stars. But navigating this system wasn't always easy. One actor so vexed by the studio system of Old Hollywood was Tyrone Power, and the favorite of his own films, Nightmare Alley, would suffer for it.

The price paid for this sort of control and efficiency is a loss of creative freedom and flexibility. Those same screen personas, carefully maintained by studios through selective assignments that played into the set image, could severely typecast stars for their entire careers. If you’re an actor comfortable keeping up an image and playing a narrow range of parts, that’s not such a bad thing. If you value challenging yourself and expanding your craft, a rigidly managed persona can be a cross to bear — all problems that studio system star Tyrone Power, unfortunately, knew about all too well.

Tyrone Power Was Blessed & Cursed by the Studio System

The biggest star under contract to 20th Century Fox in the 1940s, Tyrone Power was the classic image of a leading man: tall, dark, and criminally handsome. His good looks came with an easy charm and athletic ability, and Fox used all three traits to build a screen persona for Power as the romantic hero of period dramas and swashbuckling adventures. Movies like Lloyd’s of London, The Mark of Zorro, The Black Swan, and Rose of Washington Square, paired with ample studio publicity, earned Power the nickname “king of the movies.” Success brought with it a lucrative salary, a procession of love affairs (the salaries helped sustain him through numerous marriages and divorces), and the adulation of legions of fans, male and female alike. By all accounts, a genuinely pleasant and modest man, Power was always quick to note the role luck played in his career. “I was the right person at the right time,” he said. But for some critics, luck and a pretty face were all he had going for him; for every Zorro, there were a handful of sappy roles Power himself conceded were, “a monument to public patience.”

Beneath the self-deprecation, the insinuation that he was nothing more than his looks hurt Power. He was deeply committed to acting as a craft. Besides loving it as work, he saw it as a legacy to maintain; both his parents were actors, as were two prior generations on his father’s side. His great-grandfather and father both trod the boards under the Tyrone Power name, his father gaining acclaim as a Shakespearean performer. From his early childhood, Power’s parents helped train him for the family business, and prior to signing with Fox, he eked out a living on the stage. It was a burning personal and professional ambition of his to have a career worthy of his forefathers, full of meaningful and varied roles.

Such ambitions reckoned without the needs of the studio system and the opinions of Darryl F. Zanuck, president of 20th Century Fox. In the early phase of his career, Zanuck helped create the house style of Warner Bros. as a writer and producer; late in life, he became infamous for promoting the careers of his mistresses and ousting his own son from Fox. In the 30s and 40s, he reigned over one of the “Big Five” studios in Hollywood, and Tyrone Power was his most valuable and favored star. The two men were close; film historian Maria Ciaccia described Zanuck and his wife as surrogate parents to Power. But as a mogul, Zanuck was exacting and uncompromising when it came to Power’s screen image. Period dramas and swashbucklers playing to Power’s grace and charm were what made him such a moneymaking star, and that was what Zanuck assigned him. Always with A-list budgets and technicians, naturally, but any notions of his handsome young protégé’s to properly act weren’t worth considering.

“You name it, he lost out on it,” Ciaccia said of opportunities for Powers quashed by Zanuck. Contracts under the studio system kept stars bound to their home companies except when loaned out. Unimpressed by Power’s supporting role in his first stint away from Fox, Zanuck never let Power outside his gates again, even for as promising a part as Ashley in Gone with the Wind. Not unlike other studio heads, Zanuck’s sense of entitlement over his star extended into his personal life. Convinced that bachelors made better box office, he tried to sabotage Power’s romance and eventual marriage to the French actress Annabella. When that failed, he sabotaged Annabella’s career. By nature nonconfrontational and loyal to a fault, Power remained a company man despite these frustrations to his heart’s desires.

Why Did Tyrone Power Defy Darryl F. Zanuck Over 'Nightmare Alley'?

World War II proved a turning point for Tyrone Power. After serving as a pilot, he returned to the studio with a new set of priorities. Efforts to shore up his first marriage were ultimately unsuccessful, but the Power acting dynasty was another matter. Courtesy of producer George Jessel, a controversial 1946 novel by William Lindsay Gresham came to Power’s attention. Zanuck declared it unfilmable, but Power saw in it the professional opportunity he longed for. The book was Nightmare Alley.

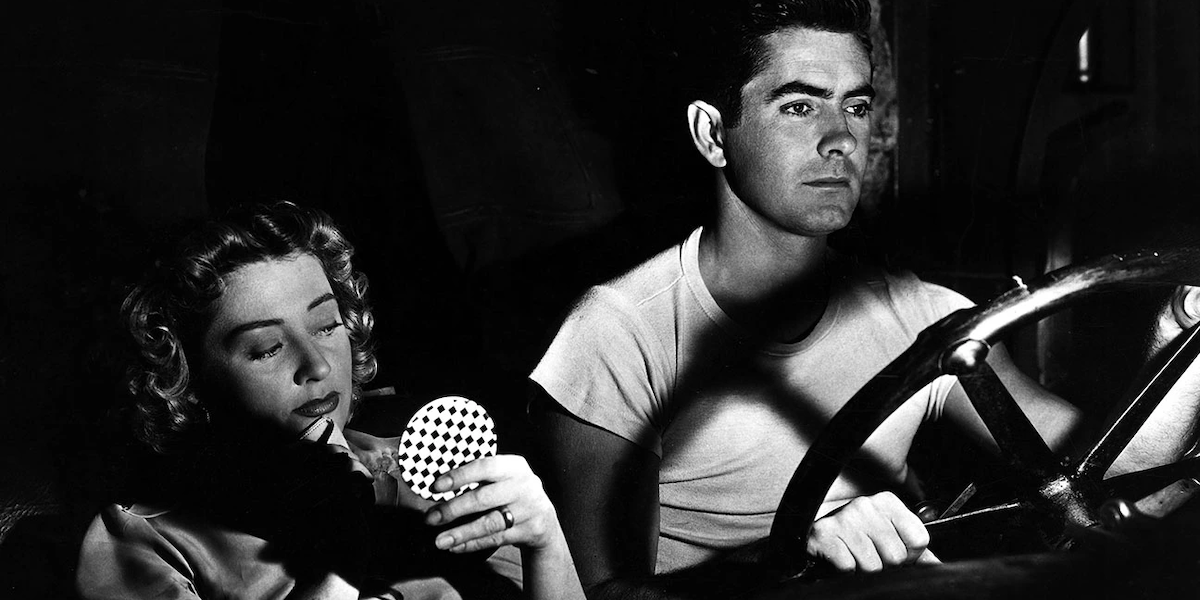

The part Power coveted from Nightmare Alley was Stan Carlisle, a conniving and self-destructing carnival barker who begins the story wondering what would drive a man to so degrading a living as the booze-soaked, half-mad geek show that entices the crowds. After learning the tricks of cold reading and a verbal code act, Stan leaves the carnival for an increasingly lucrative career as a psychic. A partnership with an unscrupulous psychologist later lets Stan reinvent himself as a spiritualist preacher. But when his deceptions go too far, Stan is left alone and betrayed by his “partner.” His life collapses into alcoholism and homelessness, and he ends up with just one option – a geek show.

'Nightmare Alley' Gave Tyrone Power the Chance To Play a Different Kind of Role

It was a far cry from the fresh-faced leading men that made his career, and that was part of its appeal to Power. Finally, he would have a chance to show a range to match his father’s. With Jessel as an ally, Power eventually wore down Zanuck’s severe reservations. When the boss finally relented and bought the film rights, he seemed to enter production in good faith. Carny antics and con men were the stuff of B-movies, but as a Tyrone Power vehicle, Nightmare Alley commanded an A-list budget and crew. And as the one most enthusiastic about the project, Power was allowed a say in it beyond his performance; he personally lobbied for Edmund Goulding as director. The movie was his baby, and for the rest of his life, it remained his favorite of his own films and his own performances.

There were compromises along the way. The Stan Carlisle that Power ultimately played isn’t quite as raw and despicable as he is in the novel. The extent to which his deceptions grow into a cult was lessened. And Zanuck insisted on a new ending. The book implies that Stan is doomed; trapped in the role of geek, he’ll stay there, biting off chicken heads until he drinks himself to death. Zanuck’s ending created a parallel between Stan and his wife and the psychic act they lifted the code from, with wife Molly being the only thing keeping Stan out of the geek’s pit. It’s hardly a happy ending – Stan’s still on the bottle with no prospect for getting off it except the grave – but it’s softened from Gresham’s prose.

Why Didn't the Studio Promote 'Nightmare Alley'?

Even with the revised ending, Zanuck hated to see his leading man as a grifter. While he had relented in getting the film made – and in style – Zanuck wasn’t about to promote a vehicle for Tyrone Power, Actor the way he would for Tyrone Power, Romantic Superstar. Scant resources were spent promoting Nightmare Alley, and it was given a rushed 1947 run in theaters that would all but guarantee the film wouldn’t make money. With the proof of a box office failure at hand, how could Zanuck be blamed if he put Power back to work in costume dramas and romances?

Power took this treatment of his pet project as a betrayal. He still had a multiyear contract to fulfill, and his relationship with Zanuck never truly severed. But Power found his resistance to the man who’d shepherded his career after Nightmare Alley. His rejection of assignments got him – Fox’s king of the movies – placed on studio suspension just as his ex-wife had once been, and as soon as he could, Power dove into stage work. Dramatic readings and touring productions granted him the creative opportunities he considered vital to his family’s legacy. As the studio system collapsed in the 1950s, there were opportunities for actors to independently develop their own projects, and Power’s Copa Productions let him take the full range of his talent to the screen. This second act to his career looked to propel him to artistic heights that would satisfy his lineage, but Tyrone Power died during the filming of Solomon and Sheba in 1958 at 44. It was, in a way, the fulfillment of another dream of his; he'd wanted to die on stage.

Shortly before Power’s death, Nightmare Alley saw decent business in a re-release. After its star’s passing, demand for it grew. TV airings and college screenings let the film percolate through American cinema culture. Guillermo del Toro’s recent effort is a fresh adaptation of Gresham’s novel without a mandated soft ending, but Power’s Nightmare Alley remains a great entry in the legacy of film noir and one of the strongest examples of his ability as an actor – whatever the efforts of Zanuck and the studio system to suppress it.