When Sidney Poitier accepted his trophy for Best Actor at the 36th Academy Awards for his performance in Lilies of the Field, he became the first Black performer to win for a lead performance in a film, accepting the award with a speech that didn’t contain a single word about this breakthrough. Even though he spoke no words of change, it would be difficult for anyone to discount that as anything less than an incredibly important moment. Poitier winning that award signaled that the old guard of Hollywood, the old way of telling stories on film was maybe on its way out. By 1967, that pendulum had fully swung, where films like Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate solidified the “New Hollywood” by raking in heaps of praise and accolades along with massive box office numbers. In 1963, however, when Lilies of the Field was released, we see a movie landscape in total flux, creating a slate of Academy Award nominees ranging from traditional Hollywood epics to European art films to boundary pushing dramas, all looking for space in the light.

The low budget dramedy Lilies of the Field, directed by Ralph Nelson, earned a Best Picture nomination alongside a pair of expensive Hollywood epics in Cleopatra and How the West Was Won, the highly personal three hour drama America America from lauded yet controversial director Elia Kazan, and the eventual winner Tom Jones, a British sex comedy from director Tony Richardson. Kazan and Richardson each scored nominations for their directorial work, with Richardson emerging victorious, in a slate including Martin Ritt for the contemporary Western familial drama Hud, boundary pushing filmmaker Otto Preminger for the religious drama The Cardinal, and the Italian auteur Federico Fellini for his dreamy masterpiece 8½. Rarely do we see that kind of disparity among the top two categories, illustrating a lack of consensus among those in an industry searching for a direction while also signaling exactly how the New Hollywood could properly emerge.

In the New York Times’ preview article for the year’s Academy Awards, Murray Schumach wrote, “There is speculation that more foreigners than ever before could win Oscars this year. It is possible that the best picture, actor, actress, supporting actor, supporting actress, director and writer all could be from outside the United States.” Ultimately, this proved to be the case for several of the seven categories due in large part to the absurd British sex comedy Tom Jones taking home the awards for picture, director, and screenplay. Even today, describing a film as an “absurd sex comedy” would basically disqualify it from contention for these awards. However, what wouldn’t be unusual today is the notion of a British film performing well at the Academy Awards being strange. At the time, Tom Jones became only the third non-American film to ever win Best Picture, the others being 1948’s Hamlet from Laurence Olivier and the previous year’s winner Lawrence of Arabia, which in pedigree and subject matter held far more appeal to traditional Oscar sensibilities.

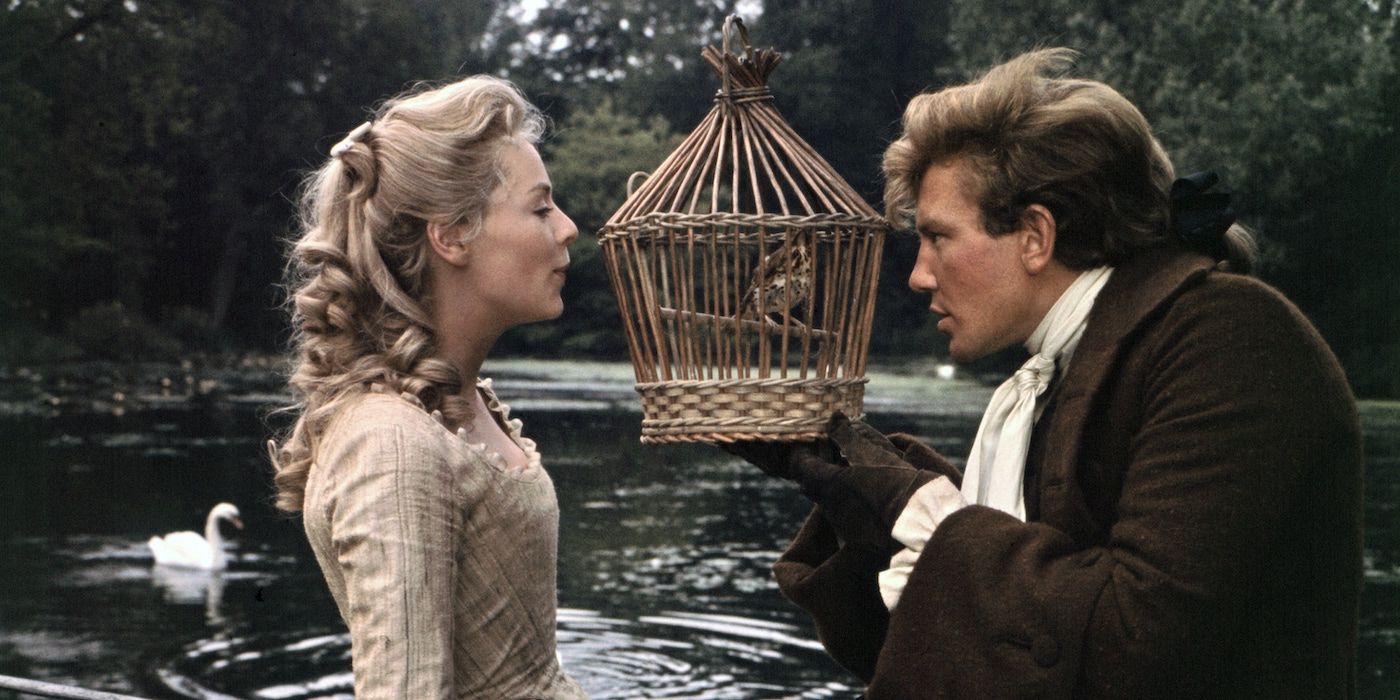

Tom Jones is crass and outrageous, containing a multitude of things played for laughs which today’s audience would find absolutely repulsive. The film’s star Albert Finney, Poitier’s most formidable challenger in the Best Actor race, was a virtual unknown in the States, only having the well-received British indie Saturday Night and Sunday Morning as any sort of claim to fame a few years earlier. It broke formal rules, such as often breaking the fourth wall or having a raunchy prologue filmed as an old silent comedy, and made for a fairly low budget. The film enjoyed a total of ten nominations that evening, the most for any film, and took home four, which tied for the most wins.

To perfectly demonstrate the clash happening in 1963, we only need to look at the other film that won four awards that night, Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s infamous production of Cleopatra. If Tom Jones sought to baulderize everything about the period epic, Cleopatra exists as the perfect punching bag. The film starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton could not have been a more publicly disastrous production. Its budget ballooned to be the most expensive film ever made, leading to the near bankruptcy of Twentieth Century Fox despite it being the number one film at the box office for the year. The affair between its two stars was tabloid fodder of the highest degree. Mankiewicz’s initial cut was six hours long, and he was fired during editing. When the film finally came out, the critical reception was decidedly mixed. However, Hollywood rallied behind its own epic and managed to get Cleopatra nine nominations and four wins.

One of the nominations Cleopatra failed to receive was for its director, Joseph L. Mankiewicz. In a highly unusual turn of events, only two films crossover between picture and director, the aforementioned Tony Richardson for Tom Jones (who won) and Hollywood prestige staple Elia Kazan for an adaptation of his own book America America. Two of the other three nominees for Best Director were Otto Preminger for The Cardinal and Martin Ritt for Hud, a film that took home two acting wins for Best Actress (Patricia Neal) and Best Supporting Actor (Melvyn Douglas). While both are American studio films, each pushed boundaries the studio system would not have allowed. The Cardinal deals with anti-Semitism and promiscuity, while the titular character of Hud, played by an Oscar-nominated Paul Newman, serves as a prototype for the charismatic antihero that would come to dominate the forthcoming New Hollywood. These films would not have been made just a few years earlier. With the sharp decline of the classic studio system and the Hays Code on its way out, American films may not have yet had the full capability to spray blood all over the screen and curse up a storm, but films like these two saw the opportunity to tackle more abrasive subjects.

Then there is the fifth Oscar nominee for Best Director, Federico Fellini, for arguably his greatest work 8½. Fellini’s surreal autobiographical film was deemed ineligible for a Best Picture nomination, due to it being a foreign language film (a rule the Academy thankfully abandoned), yet still managed a haul of five nominations, winning two. He had previously earned a director nomination two years earlier for La Dolce Vita, along with a bevy of foreign language and writing nominations going all the way back to the screenplay for Rome, Open City in 1946. Support for a film like 8½ shows the growing respect in the industry for the daring films coming out of Europe. Because of Fellini’s reputation prior to this film, it would obviously get more traditional eyes on it than Contempt from Jean-Luc Godard, a young buck renegade at the time, but the dreamlike 8½ is anything but traditional.

The disparity between the Best Picture and Best Director nominees demonstrates a dichotomy reminiscent of the very first Academy Awards, where Best Picture was essentially split into two categories. William A. Wellman’s Wings claimed the title of the first winner for the top prize, but the Academy featured a category that year they would not repeat called “Best Unique and Artistic Picture,” which would be awarded to F.W. Murnau’s romance Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans. When the Academy first started, they made a decisive effort to spotlight films for their aesthetic and bold contributions to the medium, an effort they immediately abandoned the following year. Since then, films that do not have the big money backing face enormous challenges breaking through the work that makes Hollywood pat itself on the back. I use the present tense because this sentiment remains true today. In 1963, films like 8½ or Hud that would have been put in that other category back in 1928 found their way in equal competition with the likes of Cleopatra and the three-director Western epic How the West Was Won (John Ford, Henry Hathaway, and George Marshall being the three directors).

Just in the previous year, classical Hollywood took total control of the Oscars. The Best Picture lineup featured three historical epics in The Longest Day, Mutiny on the Bounty, and the aforementioned winner Lawrence of Arabia, alongside the crowd pleasing musical The Music Man and prestige literary adaptation To Kill a Mockingbird. Not only were they the five nominees, they were also the five most nominated films of the ceremony, with Lawrence ultimately taking home a whopping seven trophies. In 1963, everything dispersed. Tom Jones and Cleopatra each took home a night’s best four awards, and How the West Was Won and Hud were not far behind with three each. The Cardinal garnered six nominations, equivalent to the blockbuster comedy It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World. Space could be found in the Best Actress category for Leslie Caron in The L-Shaped Room, as an unmarried pregnant woman who does not want to marry the father, and Shirley MacLaine, as a French prostitute, in the romantic comedy Irma La Douce from Billy Wilder.

In places, the Academy played it safe and took some risks in others. 1963 threw everything at the wall and saw what stuck. The ceremony even had plenty of quirks of its own. To return to Poitier, he was the only acting award winner to attend the ceremony and make an acceptance speech, and Sammy Davis Jr., presenting the now defunct award Best Adapted Score, had his own Moonlight/La La Land snafu after being given the envelope for the Best Original Score category. How could a night that showcased the confusing state of the film landscape not contain some confusing moments of its own? Plenty has been said on the effect the New Hollywood had on the film industry especially in 1967, but you see so many of the seeds being planted for that kind of film’s mainstream acceptance up and down 1963’s slate of nominees. Tom Jones, Hud, 8½, and Lilies of the Field needed not only to set the stage for a film like Bonnie and Clyde to upend Old Hollywood, but they needed to prove they could stand right next to Old Hollywood first and show the entire industry there truly was a place for more daring subject material, different character types, and innovative filmmaking techniques. They succeeded. Hollywood came back with a vengeance the next year with My Fair Lady. However, the space had been made, and more and more people were going to try and fill it by pushing the envelope.