Cinema has a long history of reflecting the cultural mores of a given decade within its frames, and the horror genre is no different. The 1950s saw the rise of atomic horrors following World War II; the 60s featured more personal and social horrors from the likes of Alfred Hitchcock, Roman Polanski and George Romero; the 70s capitalized on stories from modern horror gurus like Stephen King and delved further into sci-fi/horror territory; the 80s focused on big-money franchises and low-budget slasher films, while the 90s took everything to the extreme, and the 00s put modern technology to work in the lucrative found-footage genre. But before any of the modern horror films made their mark, there were decades of early cinematic pioneers paving the way for everything that would come later.

The earliest of these films were experimental by design and by necessity. Georges Méliès' 1896 short Le Manoir du Diable or his 1898 short La Caverne Maudite are two of the oldest known films, as are the Japanese horrors Bake Jizo and Shinin no Sosei, both from 1898. It's in the first 20 years of the 20th century that we see cinematic representations of Edgar Allan Poe's work like D.W. Griffith's The Sealed Room in 1909, the 1912 Robert Louis Stevenson adaptation Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and Thomas Edison's production of Frankenstein in 1910, among others. It wasn't until the 1920s that films reached significant runtimes, although the films with macabre elements weren't dubbed as "horror" films until the genre's boom in the 1930s.

So it's back to the bygone era of silent film and black-and-white pictures that we go in this list, selecting the finest examples of horror cinema from Pre-Code Hollywood. We include the soundless horrors of early German Expressionism and their reactionary World War I themes, many more adaptations of classic stories by Poe and other literary giants, the hugely influential monster universe of Universal Pictures, and taboo films that found themselves heavily censored and even banned after release. Get to know some old favorites alongside some horror icons that might be new to you in our list of the Best Horror Films from 1900 to the 1950s below:

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

Starting chronologically, as we did in our review of Edgar Wright's 1,000 Favorite Films list, we'll start this list with the 1920's silent film, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Director Robert Wiene's tale about a traveling showman and his fortune-telling somnambulist (a.k.a. sleepwalker) is a haunting example of the absurd angles and exploration of madness that's at the heart of German Expressionism, but it's also an outgrowth of the fears and experiences brought about by World War I. Screenwriters Carl Mayer and Hans Janowitz brought their pacifist and anti-authoritarian message to the script, a message the rings loud and clear throughout the picture. However, the bookends of the film's framing story serve to undercut that message rather than underscoring it. This interpretation may be a subject of debate still, but its place in horror history is rock-solid thanks to Cesare the Somnambulist and the beastly, duplicitous Dr. Caligari.

The Phantom Carriage (1921)

Another touchstone of horror from the silent film era is the Swedish picture Körkarlen, literally "The Wagoner", or as its U.S. title calls it, The Phantom Carriage. The film's release came with an early touch of viral marketing since it was released on New Year's Day in 1921 and, as the story goes, the last person to die before the New Year becomes Death's carriage driver and soul collector for the following year. This fantastic premise sets up a story about a dysfunctional family as told through a relatively advanced narrative structure using flashbacks within other flashbacks and special effects achieved through double exposure. In The Phantom Carriage you'll find early echoes of such redemptive tales as Charles Dickens' "A Christmas Carol" or even Frank Capra's 1946 holiday classic It's a Wonderful Life. This tale deals with Death more directly than those Christmas movies. In fact, it's cited as a major influence on Ingmar Bergman who would would revisit Death in the 1957 film The Seventh Seal. It's also rather apparent that The Phantom Carriage influenced Stanley Kubrick since there's a scene that clearly inspired a classic moment in The Shining nearly 60 years later. That alone makes this film a must-watch.

Nosferatu (1922)

Staying in the realm of silent films and visiting the second of Wright's 1,000 favorite films, the next installment on this list is F.W. Murnau's 1922 icon Nosferatu. This was actually an unauthorized adaptation of Bram Stoker's "Dracula" novel but remains one of the best examples in the property's long history. (The film itself was almost erased from existence due to a stipulation in a lawsuit from Stoker's estate.) Though the names are changed in this account, the basic plot points still follow that of the 1897 novel. And for my money it offers one of the creepiest depictions of the title character ever. This is no suave, sophisticated count but rather a reclusive, animal-like creature, though certain elements--subsisting on blood, sleeping during the day, and eschewing sunlight--are intact. Max Schreck may not have brought the sex appeal that Bela Lugosi would famously employ less than a decade later, but his vampiric version still haunts our dreams just the same.

The Phantom of the Opera (1925)

In the pantheon of names connected with early cinematic horror, there is but one family that boasts the name of Chaney. It's to Lon Chaney Sr. we look to in this installment. The Phantom of the Opera, in which he plays the title terror, is one of Chaney's most well-known roles but also among his last. Set in the Paris Opera House "rising nobly over medieval torture chambers," this film is a classic example of contrasts: the beauty and grandeur of the stage and theater clashing against the mechanisms behind the curtain and the depths of the opera's catacombs, love against lust, ambition against obsession, and beauty against the beast.

Except this love story takes more inspiration from the one-sided romance of Hades and Persephone than from anything in Disney's storybooks. Obsessed with an up-and-coming opera singer, the Phantom goes to great lengths to help further her career, as long as she promises to forsake all others in order to become his bride. What follows is a thrilling cat-and-mouse chase between the heroes of the story and the scheming, disfigured Phantom who haunts the hidden places of the Opera House. Notable for Chaney's self-devised makeup, which was kept secret until the film's premiere, it also features a bit of classic "mob justice" when it comes to dealing with the villain. This "culturally significant" picture was the first in Universal's string of monster movies that would become a sub-genre unto themselves in the years to come.

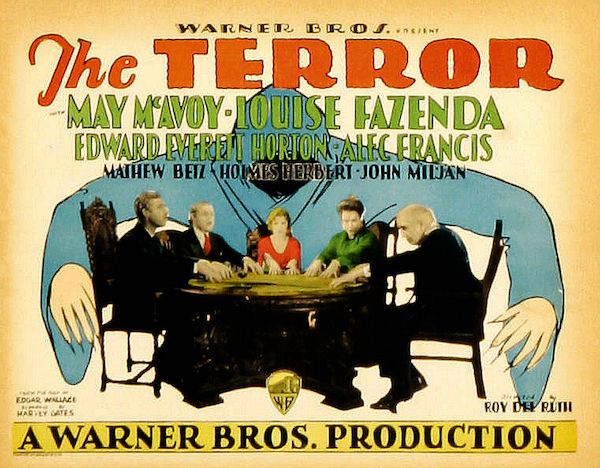

The Terror (1928)

Notable for being Warner Bros. second "all-talkie" picture and the first horror film with synchronized sound (complete with creepy sound effects), Roy Del Ruth's The Terror adapted a play of the same name by Edgar Wallace. An early example of the slasher genre, which was relatively rare when considering all the monster pictures prevalent at the time, the story followed guests of an English country house converted into an inn which is plagued by a mysterious murderer known only as "The Terror." The mystery killer is revealed after a particularly murderous night, but you'll have a tough time tracking down a copy of it to watch since the film is considered lost. For some movie critics of the time, that comes as a blessing (the more things change...), but for horror aficionados, it's an unfortunate reality.

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931)

Paramount Pictures gets in on the fun with one of 1931's many monstrous pictures. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde opens with the now-iconic horror music: Bach's Toccata and Fugue in D Minor. While that's aurally interesting, the more intriguing hook to the start of this film is the visual perspective. The audiences watches through the eyes of Dr. Jekyll (Fredric March, and it's pronounced Gee-kill as Robert Louis Stevenson himself is said to have pronounced it), a clever use of first-person point of view that allows director Rouben Mamoulian to play with some mirror effects. It also introduces a shifting frame of reference, one that slides from Jekyll to Hyde and back again depending on just which personality is in control at the time.

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde succeeds quite well in portraying the madness that lurks within all of us. Hyde is, in my opinion, the least frightening or memorable of this era's monsters, but his unhinged mania, unfettered lust, and swollen pride make for a wonderful contrast to the studious, charitable, and romantically committed Dr. Jekyll; the performance earned March his first Academy Award. The film was quite risqué for its time, with respect to Miriam Hopkins' provocative-yet-outmatched nymph Champagne Ivy. In the end, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde works as an excellent portrayal of an addict who is unable to resist his base urges after indulging in them for so long. The punishment for this character flaw is nothing short of the loss of everything Jekyll holds dear, including his very life. And in a storytelling tactic that will be often repeated after this film, the title monster reverts back to his more innocent form in death, forcing us to ask the question as to which side of his personality was actually his natural state, Jekyll or Hyde?

Dracula (1931)

Arguably the icon of monster movie icons goes to Bela Lugosi's suave and sophisticated portrayal of the title count in one of the most imitated movies in motion picture history. Director Tod Browning came into the production with a wealth of silent films under his belt and a number of collaborations with actor Lon Chaney. After Chaney's death in 1930, Universal Pictures hired Browning back for Dracula, a picture fraught with budget constraints and studio interference. Unlike the previous adaptation Nosferatu, this was an authorized production of "Dracula" since Hollywood producer Carl Laemmle, Jr. legally acquired the rights to the novel, hoping to bank on the success of the 1924 play by Hamilton Deane and John L. Balderston.

There's a good chance that if you know one monster movie from pre-1950, it's Dracula, or at least the version of the vampire that Lugosi has stamped into cinematic history. This on-screen version seen by untold millions by this point was originally honed by Lugosi himself in the Broadway play, but casting disagreements almost landed an entirely different actor to play the title antagonist. You could probably put together a satisfying dissertation on the interconnected inspirations among Stoker's story, the play adaptation, Nosferatu, and the Browning picture without even having to touch the legacy that this version of Dracula has engendered. This one's a no-brainer, as is the next film on the list, pun intended.

Frankenstein (1931)

If Dracula wasn't your cup of 1930s monster-movie tea, then there's a very good chance that director James Whale's Frankenstein was. Boris Karloff burst onto the scene in a big way as the Monster in this briskly paced mad-scientist thriller that's arguably every bit as influential as Dracula, if not more so. Thanks to Laemmle Jr.'s foresight in landing the rights to Dracula and that film's nearly instantaneous success, Universal Pictures greenlit a number of monster pictures, of which Frankenstein would be next. It also features a curious introduction by actor Edward Van Sloan who warns the audience that the story of Frankenstein might horrify us, which of course only added to the titillation.

Despite its relatively short runtime of 70 minutes and its prevalence in our modern culture, Frankenstein was heavily censored in certain regions upon release. One scene that was long considered controversial--and is probably my favorite part of the whole picture--is when the monster throws a little girl into the lake, ultimately drowning her. Other censors asked to cut Dr. Frankenstein's line about knowing what it's like to "be God", the same line in which he famously shouts, "It's alive!" The most egregious censorship would have trimmed the film down to nearly half its length. Luckily, thanks to modern conveniences and the preservation of this film by the Library of Congress, we have viewing access to the entirety of this classic horror icon.

The Island of Lost Souls (1932)

Any movie that can boast "The Panther Woman" as part of the cast is clearly a must-watch on this list. If you needed more evidence as to why it should be included, Erle C. Kenton's The Island of Lost Souls was the first film adaptation of H.G. Wells' 1896 science-fiction novel "The Island of Dr. Moreau." (The screenplay was written in part by notable genre author Philip Gordon Wylie.) Lugosi stars as the Sayer of the Law, his most wolfish character to date, though it's much more of a supporting role than the movie poster might indicate. The real power player here is Charles Laughton as the brilliant but twisted Dr. Moreau, who attempts to play God by creating creatures who are half-human, half-beast.

This is a classic tale that effortlessly combines a number of horrors together into one chilling, unforgettable narrative. Moreau not only brings these hybrid monstrosities into being through fringe science, he also controls them with his own set of laws, the crack of his whip, and the promise that any bending or breaking of these laws will result in a visit to the house of pain. It goes without saying that Moreau cannot maintain control over his island and its population forever, but the manner in which chaos replaces order in this film is a truly haunting sequence. It's a conclusion best experienced for yourself, just don't watch it too close to bedtime.

Freaks (1932)

Moving away from the realm of famous Universal Monsters and into the taboo, we have Browning's follow-up to the very successful Dracula with MGM's first horror picture, Freaks. This much-maligned film, which is nearly impossible to categorize due to how unique it is, elicited strongly negative reviews from critics, heavily censored edits before release, was pulled before completing its domestic run, and suffered a sizable loss at the box office. The poor reception essentially ended Browning's filmmaking career and burned off any cachet Dracula had earned him.

And yet Freaks found a resurgence in popularity among counterculture groups and film buffs in the last 40 years or so. The film, which no longer exists in its original, even more shocking version, tells of a troupe of circus performers including a collection of "freaks" put on display for paying audiences. The cast included actual performers, people with physical disabilities or abnormalities, and other conditions, as well as "normal" actors playing the more traditional roles. However, Freaks is anything but traditional since it portrays the beautiful Cleopatra (Olga Baclanova) and the strongman Hercules (Henry Victor) as truly ugly and corrupt people attempting to take advantage of the "freaks." Let's just say that they get what's coming to them.

Freaks might not seem like a horror movie until you get to the last 15 minutes or so, at which point it becomes rather terrifying. So if you haven't seen it, do yourself a favor and seek it out. If you have seen it, considers yourself one of us, one of us!

The Old Dark House (1932)

Another overlooked horror classic from this era is The Old Dark House, an effort from Whale who once again directs Karloff but in a bit of a different role than that of his famous stomping monster. It was a bit lighter than Whale's earlier works, but far from being a horror-comedy like the Abbott & Costello efforts that would come later. The film also opened with a producer's note "settling disputes" about any similarities in appearance to Karloff's Frankenstein monster and his odd, savage butler Morgan in The Old Dark House, even though Universal produced both pictures.

This film was based on the J.B. Priestly novel "Benighted "(1927). It centered on a bickering newlywed couple and their carefree friend who were traveling on the road when a terrible storm and a rockslide forced them to take refuge in a nearby home, occupied by the Femm siblings. They're soon joined by another jovial couple seeking to escape the storm, but it becomes quite clear that the Femm family is far from hospitable and has, in fact, been touched by madness. The classic tropes of haunted house movies are on full display here but they don't feel tired thanks to excellent performances by the cast. Karloff is actually the least among them since his drunk, savage brute of a character only mumbles, shambles, and slugs his way through the picture. The Femm Family, however, is a wonderfully twisted addition to a familiar story.

The Mummy (1932)

Only a year removed from fellow Universal Monsters Dracula and Frankenstein, Karl Freund's The Mummy sees Karloff taking on his second most-famous role (unless you count his Grinch-related performances, which you probably should). Rather than adapting an existing work of horror fiction, The Mummy was inspired by Howard Carter and his archaeological team opening Tutankhamun's tomb in 1922, and the supposed curse that followed them. Lo and behold, another Universal Monster was born!

The story's focus was on the reanimation of the ancient Egyptian mummy Imhotep (Karloff) who searches through modern Egypt for his reincarnated lost love. Imhotep is resurrected through a magic scroll, which is an interesting change from the previously seen plots that used pseudoscience as a pathway to transformation. The Mummy has more in common with Dracula in this regard since they're both based in folklore, mythology, and magical abilities than anything in the mad science sub-genre. The ambitious film spanned thousands of years of history and introduced concepts of reincarnation and ancient Egyptian religious practices to Western audiences already hungry for anything to do with pyramids, mummies, and the exotic pantheon of gods. And while it was a box office success, the film spawned four remakes in the 1940s, but no official sequels.

The Bride of Frankenstein (1935)

The only sequel you'll find on this list comes in the Frankenstein franchise. It's one that was long considered lesser-than by critics and moviegoers alike, but has more recently found a new audience and appreciation. Rather than opening with a warning from one of the actors, it instead starts out with somewhat of a framing story: Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and Mary Shelley are gathered in the parlor, in which Mary reveals that her characters survived the first tale and lived to tell another one, as did director Whale.

And this tale is, at times, arguably more comedic in tone and more outlandish in character, especially considering the displayed collection of miniature homunculii and the shrill, shrieking Minnie (Una O'Connor). But it also gives Dr. Frankenstein (Colin Clive) a chance to redeem himself under the even more insane Dr. Pretorius (Ernest Thesiger). Pretorius wants Frankenstein's assistance in bringing another life into this world, a bride for his previous monster, thus furthering the "playing God" theme. Frankenstein refuses, having learned his lesson, but has his hand forced into assisting by Pretorius and his very own creation itself. As much as I love watching Karloff's monster learning to speak, smoke, and appreciate a good bit of violin music, it's still heartbreaking to see him rejected by townspeople, his creator, and his fellow monsters alike. The final sequence in which the monster forgives Dr. Frankenstein while dooming himself, Pretorius, and the newly reanimated bride (iconic lightning-struck beehive hairdo and all) back to the grave is a surprisingly sympathetic moment for such a monstrous creation. It's a worthy sequel that some now consider Whale's crowning achievement.

King Kong (1933)

If ever there was a movie monster to rule them all, it was King Kong. This RKO monstrosity could have easily crushed the entirety of Universal Pictures' monster line-up under its gigantic simian fist, but was gentle enough to handle Fay Wray with care even while climbing the Empire State Building and swatting down attack planes.

King Kong could be argued to be a fantasy adventure film, but it certainly has horror elements. The spooky Skull Island, situated within treacherous waters, is home to a native human population, extant dinosaurs, and giant apes, of which Kong reigns supreme. The real horror comes not when the film crew invades his home island, but when they drug the monstrous beast and haul him home to New York City. Imagine such a primal, prehistoric terror loose in the modern urban center of the known world; it must have had New Yorkers glancing to the sky-high profile of the Empire State Building on occasion to ensure it wasn't under assault from man nor beast.

And yet Kong is one of the earliest examples of a sympathetic monster, a creature dragged from its home to be put on display only to die protecting itself (and its loved one) under confusing and foreign circumstances. King Kong succeeded at showing the powerful side of Mother Nature and the monstrous side of man, but owing to a lack of giant apes in the real world, man's shortcomings were the message of the day, then and now.

The Invisible Man (1933)

Whale returns once again for another Universal Monster. This installment introduces Claude Rains in his first American film role as The Invisible Man, a character which he performed mostly as a disembodied voice off-screen. He does appear briefly at the end of the film, but spends most of his screen-time wrapped up in more bandages than Karloff's Mummy.

Based on H.G. Wells' science-fiction novel of the same name, The Invisible Man returned to the realm of science to explain the main monster's predicament. A chemist by the name of Dr. Jack Griffin had discovered the secret of invisibility during a series of tests on the obscure drug monocane. The dangerous drug not only makes Griffin permanently invisible, it drives him mad (or, arguably, allows his own vices to consume him). Griffin ropes unwilling participants into his plan which involves theft and wanton murder in order to gain power. Much like earlier villains brought about by meddling in science that ought not to be meddled with, the title antagonist is brought low by mob rule and his own pride, eventually confessing his sins and reverting to his previous self as death takes him. The beats are similar here, but the style is all its own.

The Black Cat (1934)

Speaking of style, here's a slick little tale of war, politics, and vengeance that works in necrophilia and Satan worshipping for good measure. Oh, and it's the first of eight movies to feature Lugosi and Karloff together on the same screen. (It's also one of the earliest films to feature a nearly continuous musical score.)

Inspired by a Poe story, The Black Cat finds Lugosi's war veteran and prison camp-survivor Dr. Vitus Werdegast at odds with his former friend and fellow soldier, the engineer Hjalmar Poelzig (Karloff). Caught in the middle of their feud is a young American couple visiting Hungary on their honeymoon. What follows after their fateful meeting is a bizarre cat-and-mouse game played between Lugosi and Karloff with the couple as the prize to the victor: Should Werdegast win, the couple will be set free and Poelzig will pay for his sins; if Poelzig wins, the couple will be sacrificed in a midnight ceremony and Werdegast will meet his maker as well. This is a crazy story that sees Lugosi portraying a crippling fear of cats, Karloff posing as a death-and-beauty-obsessed lunatic dabbling in dark magic, and a rather icky twist that further complicates the relationship between the two former soldiers. The Black Cat ends with a bang, so definitely seek this one out if only to see the horror masters on screen together but outside of their usual monster make-up.

The Raven (1935)

In another collaboration between Lugosi and Karloff that was inspired by Poe (this one much more obviously), The Raven sees their villainous characters working alongside one another rather than against each other. While this partnership is tenuous at best (and comically absurd to begin with), it's fantastic to see it play out on screen.

The Raven has two interesting things working for it: the interplay between Lugosi and Karloff, and the bizarre obsession Lugosi's character, Dr. Vollin, has with all things Poe. Vollin, a gifted but eccentric surgeon, admits to having built a number of Poe's most famous contraptions (notably a pit, pendulum, and shrinking room) in his very house. And making a long story short, Vollin seeks to use his self-made torture chamber on the Thatchers, a family which he helped by using his particular talents but who ultimately insulted him. Vollin enlists the help of escaped murderer Edmond Bateman (Karloff) in this endeavor, though only through cruel trickery. It seems that Bateman no longer wishes to be so evil, that he's sick of being ugly and therefore, in his mind, feeling compelled to do ugly things. So when Vollin offers to fix Bateman up with some plastic surgery in exchange for his help, it seems like the perfect match. What follows is a descent into madness, betrayal, and obsession that lets both Lugosi and Karloff loose upon the screen.

The Wolf Man (1941)

The last of our Universal Monsters is writer/director George Waggner's The Wolf Man, the first of our horror films to see Lon Chaney Jr. pick up the mantle from his late father. It wasn't the studio's first werewolf movie--the less commercially successful Werewolf of London debuted in 1935--but it would go on to shape the werewolf mythology for decades to come. This would include Chaney Jr.'s reprisal in the role for four sequels. (Lugosi and Rains have supporting roles in this first installment, as well.)

Continuing the theme of "Americans in Europe in peril," The Wolf Man sees Chaney Jr. as Larry Talbot, a practical man who returns to his ancestral home in Wales following his brother's death to reunite with his estranged father. In addition to his family entanglements, he also gets involved with a local woman and her friend, a relationship that eventually puts him in direct contact with a savage wolf. Ultimately, this event transforms his entire life thereafter, right up until his heartbreaking death. The Wolf Man may not have the best special effects (even if the wolf man make-up itself is still iconic) but it's an absolute classic in the genre.

Cat People (1942)

Jacques Tourneur's Cat People is a horror movie of a very different sort. Outside of the realm of more common mythological monsters, this title terror is taken from Val Lewton's short story "The Bagheeta" published in 1930. The story follows an American man named Oliver Reed (Kent Smith) who falls for a Serbian immigrant named Irena (Simone Simon), who has the peculiar belief, based on the legends from her home village, that she'll turn into a wild cat if and when she's sexually aroused. As you might expect, this belief complicates their relationship, but they marry just the same. The real complication arises when Oliver begins to fall for his co-worker, Alice (Jane Randolph). Hell hath no fury like a cat-woman scorned.

Cat People is unlike any of the other horror films on this list. Irena does not transform in full view of the camera on a whim or by some chemical obsession, but by the very act of sexual attraction. Oliver, frustrated by a sexless marriage and inability to help Irena overcome her superstition, enlists in the help of a psychiatrist and also confides in Alice about his troubles. These decisions only serve to further complicate their relationships and feed Irena's jealousy to the point that it grows out of control and leads her to stalking Alice through the streets and into her own home. To make matters worse, an affair with the psychiatrist brings Irena's latent fears and beliefs to life in horrific fashion. Cat People dabbles in such unusual topics for the time as powerful and dangerous women, the dangers of sex and seduction, divorce, femme fatales, and mental illness. Its conclusion, however, is anything but uplifting, so be prepared.

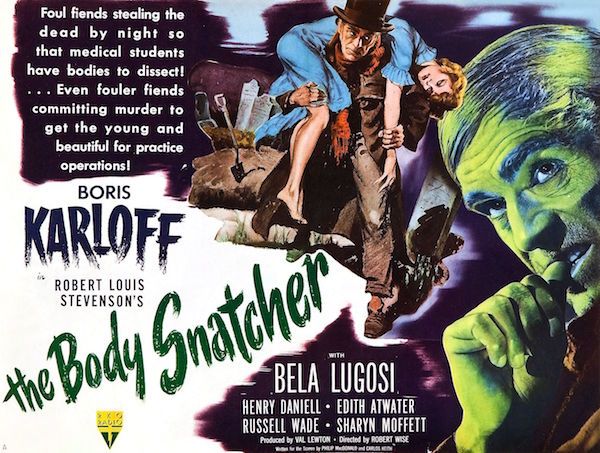

The Body Snatcher (1945)

In the running for the most disturbing ending on this list of films is Robert Wise's 1945 effort, The Body Snatcher. This is the last film to feature Lugosi and Karloff on screen together at the same time (though Lugosi's role is rather reduced), and was based on another short story by Robert Louis Stevenson. This time, the story took place in 1831 in Edinburgh, only a few years after the very real Burke and Hare murders in which 16 people were killed in order to sell their bodies to Dr. Knox for dissection at anatomy lectures.

While one of the main plots of this film centers on a young medical student and his attempts to help the paraplegic daughter of a young woman, the horror elements of the plot take quite a different course. Karloff stars as John Gray, a cab driver by day and a resurrectionist by night; he delivers freshly dug-up (or even freshly murdered) corpses to physicians for dissection. The medical student accepts these bodies with the approval of his mentor, Dr. MacFarlane. When the not-so-good doctor's other assistant (Lugosi) turns up dead after trying to blackmail Gray, the resurrectionist threatens to expose the truth: that MacFarlane's mentor was Dr. Knox and that he had a hand in the Burke and Hare murders.

What follows is a tense stand-off between the two men that only becomes more and more nerve-racking as the story moves to its inevitable conclusion. The final few moments are absolutely worth a watch and the resolution of their struggle is made all the more meaningful thanks to an impeccable build-up.