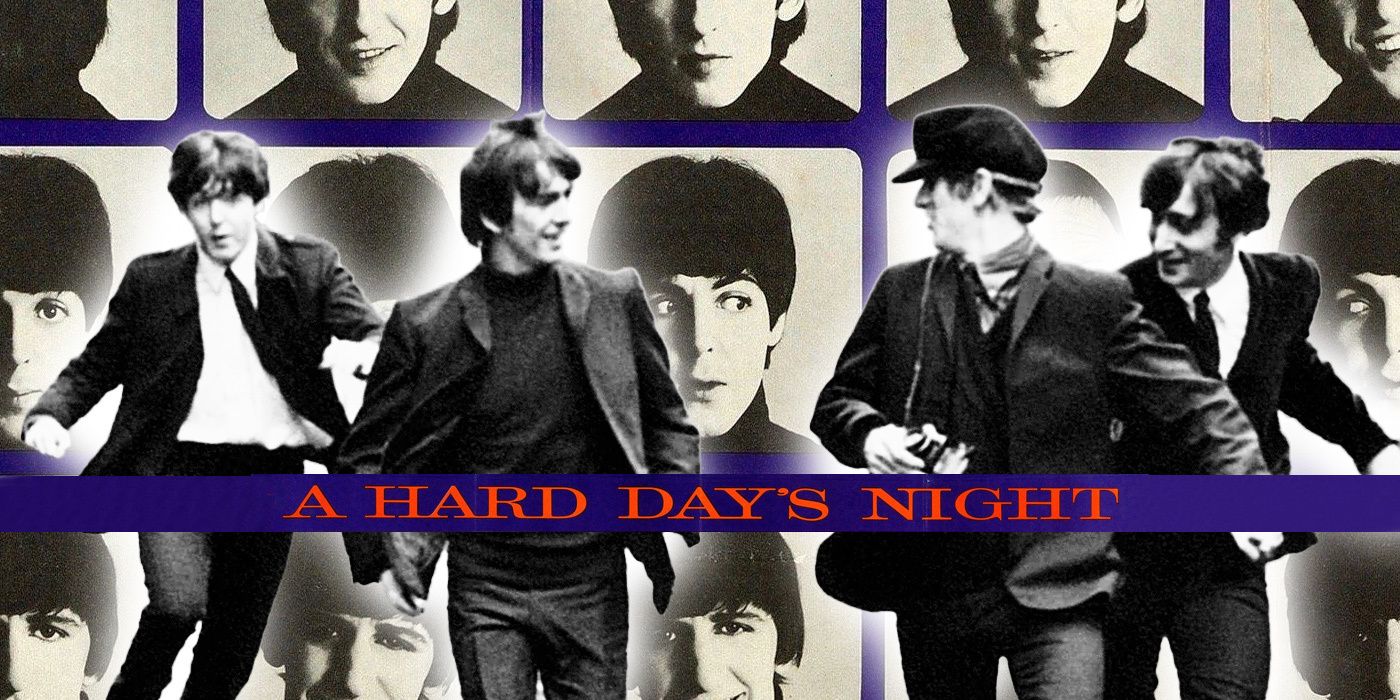

Pang! Like The Beatles' album of the same name, A Hard Day's Night opens with an electric strum of a guitar—electric in this case being both literal and figurative. The film begins in an excited frenzy, with the Fab Four running from a screaming crowd of teenage fans, soundtracked by the movie's title song. As the music plays out, the boys continue to run and one joke follows the other. Immediately, the tone is set: welcome to a youthful, inventive film that sets to capture the cultural phenomenon of its stars while allowing itself the freedom to mock the very concept of making a traditional musical picture. The band cracks wise to one another and those they reluctantly work with, catchy songs begin spontaneously, and gags are thrown about in a rapid-fire manner. At times, it's almost hard to keep up.

It's easy to take A Hard Day's Night for granted. So many movies have studied the film's formula and copied it that its actual brilliance may often feel lesser than it is. One can see the influence in any number of comedy films and programs (Monty Python's Flying Circus, and the Austin Powers series, just to name a few), just as one can see how it changed what a musical could be. Many musicals, specifically rock musicals, can trace their influence to the freshness and youthful wonder of the Beatles' first film. It proved that they could do anything. They were no longer confined to the previously established limits of what could be accomplished.

Before A Hard Day's Night, the subgenre of rock musicals was primarily monopolized by Elvis Presley-starring pictures and their many imitators. Too often, they were formulaic, and they existed solely to market a new batch of Elvis songs while ensuring that the King of Rock still looked hunky and cool. While there are a number of films from this subgenre good enough to warrant watching (Jailhouse Rock and King Creole) they mostly become lost amongst themselves. There were too many of them, and too few were inventive enough to make a distinction from the rest. You can generally predict the plot beats: a handsome good-boy flirts with being bad, seduces a woman, and sings his way to a happy ending, all while looking damned cool. Without Elvis, the movies had little to nothing, and practically every rock musical from this era suffered from the same ailments.

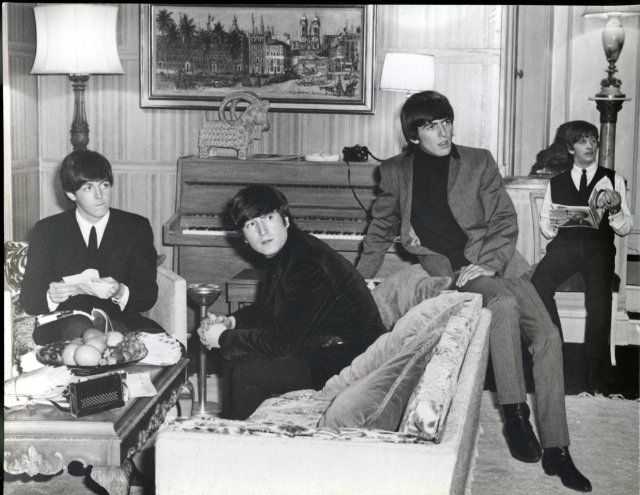

Fortunately, Richard Lester and The Beatles changed things. Just as John, Paul, George, and Ringo proved to be the poster children for the cultural and musical shift of the 1960s, their first feature film was a manifesto for a new generation of musical films. In A Hard Day's Night, The Beatles are young, smart-mouthed, and seemingly inconvenienced by their fame. They crack jokes and goof off with a sort of carefree joyousness that defies the romanticism and seriousness of the prior rock films. Their responses to interview questions are mocking and insincere. They aren't overtly trying to be rude. They're just trying to have fun.

In the case of the movie, setting out to have fun is invariably a success. Almost 60 years later, most of its humor still sticks. Shockingly, it hardly feels dated at all, and in fact, it still feels fresh. Even if the opening scene has been frequently spoofed, it's hard not to see it now without knowing that something special is happening. The viewer isn't given a chance to breathe. The film begins with a bang, and it never stops running from there.

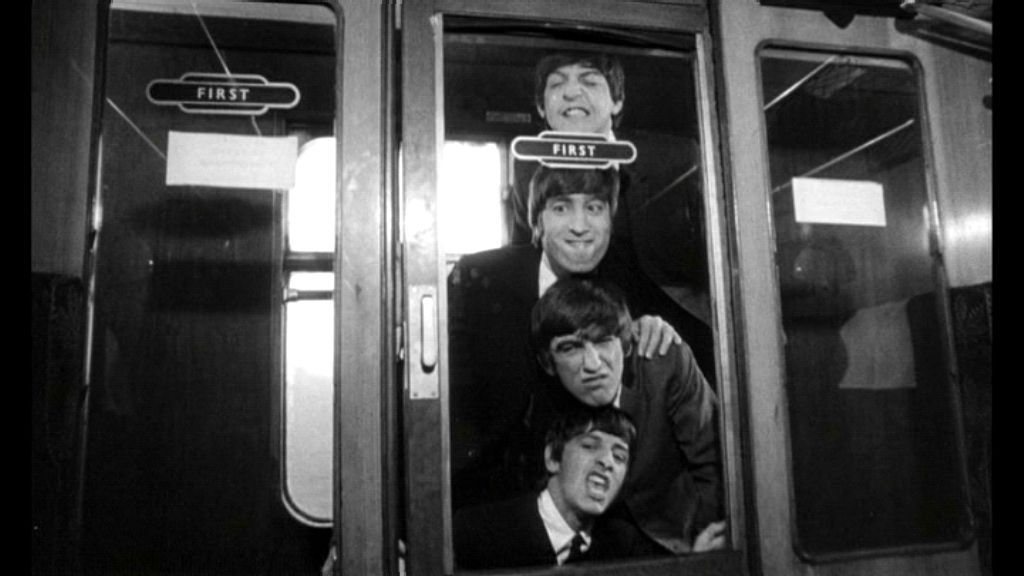

Lester follows the Beatles like a documentarian, with a stylized black-and-white camera probing the boys as they wander the city, prepare for gigs, and break spontaneously into song. Inspired by the cinéma vérité style of filmmaking, the camera moves freely throughout dressing rooms, concert halls, and city streets. It's often up close and personal, capturing the band with the immediacy of a legitimate documentary. As a result, the film feels spontaneous. The camera is a fly on the wall, serving solely as a window to the band and their delightful world.

One can trace much of Lester's influence to the inventive filmmaking found in movies like Breathless—whose jarring jump cuts revolutionized cinematic editing and can be found in this very film—but with A Hard Day's Night, Lester brought these ideas to a broader market. It's not so much that he copied the works that were changing cinema before him, but more that he riffed on them to steer into a different direction, a popularization of a prevalent but niche trend. Crucial components of the greatest hits of the French New Wave were snuck into the mainstream. Presley's pictures had a comparatively stale presentation. In contrast, A Hard Day's Night is the cinematic equivalent of a tongue stuck out, a sort of refusal to behave sternly.

This lack of gravity is taken further by the film's humor. The movie is laid-back and self-acknowledging. With a razor-sharp script honed with wit, it has an upbeat drill of punchlines and quotable jokes that many comedies would be lucky to have. "How did you find America?" an interviewer asks in one scene. "Turn left at Greenland," John drily replies. Quips are exchanged at the breakneck speed of the Marx Brothers. Many films might reserve the wit and humor for a single member of the group, but not this one. In A Hard Day's Night, there isn't exclusively one comic or jokester; instead, each of the boys is given numerous zingy lines fitting with their quirky personas. Even Ringo, whose teasable, slightly-lesser-popularity is itself spoofed by the film, has no shortage of hilarious quips.

It isn't just an infectiously comic script. There's also the cartoonish playfulness of the film, in which bits that would fit into the comic absurdity of a Bugs Bunny or Road Runner short juxtapose against the realistic visual style. It's part of what makes the film so revolutionary. Here are four of the world's biggest rock stars, and they're making a picture that never has any intention of taking itself—or its stars—seriously. Gags that make no logical sense fit snugly alongside performances of some of the band's biggest hits. What would eventually become a multi-platinum-selling record is visualized with a preposterous occurrence of Ringo Starr accidentally leading a young woman into a hole in the road.

Richard Lester has often been exalted with the title "The Father of the Music Video." To a large extent, this designation is true. If Lester's audiovisual language is predated by the promotional clips and short films originating in the 1950s, A Hard Day's Night invented the contemporary style of what a filmed portrayal of a piece of music could be. In the film, Lester cuts footage according to musical beats, just as he intersperses live-filmed performances with narrative footage corresponding to the song. The camera moves where it chooses, faces of the band are cut against footage of an ecstatic crowd, the always-active hands of the musicians are captured with close-ups and zooms.

Just as countless numbers of musical acts sought to capture the success of The Beatles, no small amount of filmmakers sought to replicate the magic of A Hard Day's Night. The Monkees had a television program stylized in a similar vein, the Dave Clark Five had their own cinematic vehicle, and the appearance of The Archies in The Archie Show mirrors the Beatles' own merging of music with cartoonish comedy. You can see bits of A Hard Day's Night in Rocky Horror Picture Show and This Is Spinal Tap.

Every once in a while a film comes around and reinvents the medium of cinema. Citizen Kane is one of them. Breathless is another. A Hard Day's Night is one of the rare works that simultaneously acknowledged what came before it and foretold what was to come. It entirely changed what a musical—specifically a rock musical—could be and what it could amount to. They no longer had to merely market their stars or capitalize on the cultural success of the music. Lester's film clearly intended to make money off The Beatles' explosive popularity, but it wasn't content with only doing that. It also wanted to make fun of itself and the movies that preceded it, laughing in the face of conformity. It deconstructed the form of the genre and rebuilt it into something carefree and freewheeling. Now, a rock musical could be anything and do anything, so long as its stars were charming and the music was good.