As illustrated by Vince Locke, A History of Violence looks furious and unstable even in its design, a scratchy black-and-white view of a small Midwest town that erupts with violence one fateful night. The characters occasionally look incomplete in composition; patches of inky black are broken up by numerous small gaps of white. On the whole, the entire graphic novel, which was published in 1997 by Paradox Press and, later, Vertigo -- both imprints of DC -- looked like a studied sketch of the events that writer John Wagner had laid out. It's a potent reflection of the themes that Wagner touches on in his story of Tom McKenna, a middle-aged family man who becomes famous overnight for heroically killing a pair of robbers who were sticking up his diner, and subsequently garners the attention of a mafia kingpin who insists he is a robber and a killer from Philadelphia. Tom McKenna, it turns out, is also a hurried sketch, a vague character created by a criminal on the run and in need of a fresh start.

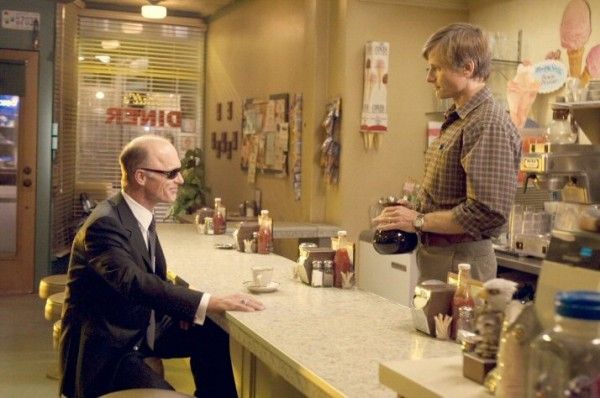

This, more or less, would also qualify as a synopsis of David Cronenberg's masterful adaptation of Wagner and Locke's graphic novel, which was one of the great films of 2005 and, arguably, the very best film of that year. Starring Viggo Mortensen in the role of Tom, the film similarly tracks aftermath of the diner owner's execution of the two villains to the appearance of Carl Fogerty (Ed Harris), a vicious lieutenant out of a Philadelphia crime syndicate who insists that Tom is actually Joey Cusack, the hot-tempered killer who ripped out Fogerty's eye with barbwire. There are other similarities in the plot of the film and the graphic novel, but Josh Olson's script takes more than a few major liberties with the source material, which is inarguably for the better. Indeed, as entertaining and admirably stylish as Locke and Wagner's novel is, Cronenberg's film reflects a distinctly American and complex view of our attitudes towards violence, its repercussions, and the very notion of who we consider heroes.

The story goes that Cronenberg didn't even know that Olson's script was an adaptation of a graphic novel when he signed on for the picture, having cited that he finds superheroes to be too adolescent for his taste. One can feel that same skepticism in the film when Tom, who tellingly has the last name of "Stall" in the film, becomes a minor celebrity for killing the two men in his diner, being labeled a hero for an act of brutal, if warranted, violence. In the aftermath, Tom wants nothing to do with the publicity: he shies away when his son, Jack (Ashton Holmes), giddily describes him as a hero, and gives nothing but curt answers to reporters who ask for him to regale them with his story. Considering the long history of Americans venerating the idea of the righteous gunman, it's not hard to see how this relates directly to Cronenberg's broader view of how, in many instances, violence has become accepted and even celebrated.

Of course, America's perception of heroic violence is at least partially rooted in the Western genre, the films of Anthony Mann, John Ford, and Howard Hawks, amongst many others, and at base, A History of Violence could be construed as a modern Western. Tom and his wife, Edie (Maria Bello), live on a small farm of sorts, and later in the movie, a crime boss mistakes Tom for a farmer. And like many Westerns, where one would have to take people at their word that they were who they said they were, the concept of identity is crucial to what Cronenberg and Olson are getting at. Is Tom an essentially good person or a villain in disguise? Can a person be both? Cronenberg is fond of close-ups, centering shots on characters' faces, and throughout A History of Violence, you can almost feel his camera scrutinizing Mortensen's face, looking for a tell to settle whether or not he is who he says he is.

Another prominent element of the film that is pure Cronenberg, as compared to the source material, is sex, which is barely brought up in Wagner and Locke's book. In the first of two remarkable sex scenes, Bello's Edie dons a cheerleading outfit for a thrill, and in doing so, Cronenberg underlines how a nostalgic image of Americana so easily doubles as a vision of perversity, much like how the gunman is both an icon of American law and everything that's wrong with it. This, coupled with the second sex scene, which features Tom and Edie having rough sex on their staircase, also bucks at the notion that All-American parents don't indulge in fetishes or any sex acts beyond an old-fashioned, missionary roll in the hay. And Edie's seeming enjoyment of the rough sex touches on the primal attractiveness of violence, even as the scene, which begins as a household argument, ultimately skirts rape.

The gap between Tom and Joey comes to a head when Fogerty comes to Tom's house, threatening to kill Jack if Tom doesn't come to Philadelphia with them, only to then be killed by Jack. Cronenberg smartly charts how Tom being revered for killing the men in the diner gives Jack the idea that bloodshed is how one acts courageous, a concept that crests when he pummels a school bully and climaxing with his killing of Fogerty. Soon after, Tom is summoned to Philadelphia by his crime-lord brother, Richie (William Hurt), and what follows is an act of savage attrition, wherein Tom finally fully confronts his past as Joey. In Richie and Joey's encounter, Richie recalls his attempt to kill his brother when they were young, only to be then beaten up by their mother, a moment that would seemingly anchor the brothers' complicated view of bestial violence. It's only after Joey confronts Richie, and their horrific past, that he can fully become Tom and return to his family.

Much like Joey's conflictive relationship with fighting and murder, Cronenberg is careful to embrace images of bloodshed without exploiting them for the basic thrill they inevitably give the audience. As anyone familiar with his work knows, Cronenberg films violence, the destruction of the physical body, with blunt yet flourishing imagery, which captures the instinctual power of violence that the graphic novel never quite conveys. At a compact 96-minute runtime, A History of Violence brings the exhilaration, terror, and essential physicality of fighting, murder, and torture to the foreground of a story that originally read more like a hardboiled crime novel. In the hands of Cronenberg, Wagner and Locke's sketch of a story becomes a riveting study of humanity's dark rampaging inner beast, which remains as potently, and unfortunately, timely today as it did a decade ago.