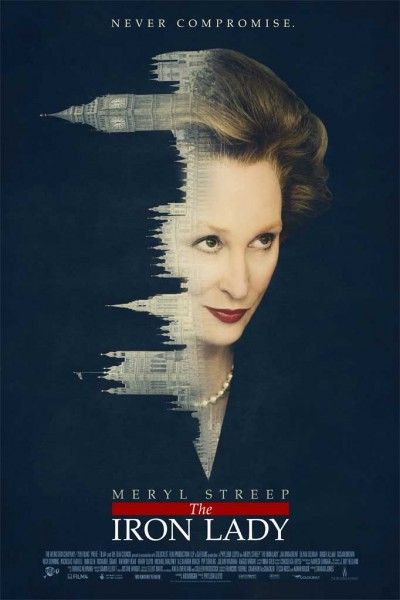

In The Iron Lady, Meryl Streep stars as Great Britain’s first female Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, in an emotionally moving and inspiring performance. From the opening scene the film is immediately gripping, with an unexpected narrative. The story glimpses into her political reign--seamlessly intertwining newsreel and rock ballads--but predominantly focuses on Thatcher's older life as she struggles with dementia. The film has many similarities to The Weinstein Company's pic from last year, The King’s Speech, in that it profiles a public figure, but chooses to spend most of the screen time on their imagined private lives, making for a film that hooks and involves audiences while educating them.

At the press junket, I talked exclusively with writer Abi Morgan, who penned both The Iron Lady and Steve McQueen’s Shame. We talk about why she chose to focus more on Thatcher’s post-political life, the universality of the film, and the themes and stories she’s attracted to as a writer. The Iron Lady opens in limited release on December 30th and it expands on January 13th. Hit the jump for the interview.

Question: I want to ask if you’re struck by how not political it is, and how personal it is. Is that something you do sort of fantasize about—a public figure and what they do in their private time?

ABI MORGAN: Yeah I think… I thought about all those moments where you see iconic political leaders, celebrities, sports stars, and you see them in the moment when they don’t realize they’re being photographed. And those are always the intriguing ones. There was sort of a fascination for me to try and write about… I tried to think about the period when I was reading about her and doing the research, and sort of thinking about her life. And I found the period that was hardest to see record of was the sort of near-present, and so that became very intriguing to me. And then I read a fascinating article by her daughter where she talked about the moment when she realized her mother was suffering from dementia and I felt that as soon as that came out into the public domain, I felt that I really wanted to write about it. I really wanted to write something that would reflect that.

And I think that’s—the dementia aspect—is one of the main things that people are really going to respond to. Whether someone has a family member or they know someone who’s experienced that--

MORGAN: I have dementia in my own family so I recognized that as an experience and I’d observed it but I do think it’s more of a universal story. I don’t think it’s a political film. I think it’s about the study of power and the isolation of power, but that’s also set against the isolation of old age and in particular, the isolation of dementia, in a way. And this is a film really about a character, Margaret Thatcher, who the past sort of attacks her and takes her hostage in a way. And so I tried to use the structure as how someone’s mind is like a flick-hold to memory. You’re trying to grab bits of information and then lose it again. And the kind of nightmare of that experience really resonated with me when I wrote it, and that’s what I sort of focused on.

I know you write several drafts—do you workshop at all?

MORGAN: Sometimes I do, it depends on different projects. I quite often workshop scripts. So you know you’ll sit with the actors and the director just to see how it’s read. But I didn’t with this one, which is interesting. I did lots of drafts. I had done a number of drafts and then Phyllida Lloyd came on as director, and obviously that brought a whole new stage of work. And when you have an actress like Meryl [Streep] who’s such a great interrogator of dramatic arc and character and has, you know, she’s worked on some of my favorite films. I knew that when she spoke, and when she heard a response and thoughts about the character and the screenplay, that they were all really worth listening to. You know most of screenplay writing is deciding which voices you want to listen to and take on board, and hers was the one I really wanted to hear.

I know you’re speaking about voice in a different context, but in terms of Margaret Thatcher’s ‘one-liners’…she has all these sort of interesting expressions or wise words…Is that something you really took from research or is some of that something you were just able to play with and imagine?

MORGAN: I think there are certain things I played with. So the doctor scene, that was an idea…there was a great saying that had been said to me before and I thought, that’s really interesting, I wonder if that would work in the context of the film. It feels so apt for her whole philosophy, so that was something I found, whereas there are other phrases, there are other little things “DT”, or, “another lotion, boss”—the kind of phraseology of Dennis [Thatcher] was very much something that I think resonates if you read his memoirs and if you read the way he’s written about, there is a certain bonhomie to his language that I filtered and put in the script. But often, you know, the process of re-writing and writing and re-writing means that you may have a brilliant phrase, but over time it distills and distorts and changes, and so a lot of it is about the essence of something that she’s said, rather than the literal taking of a quote.

The scene between the doctor is one of the more powerful scenes, and one which seems to really sum-up Margaret Thatcher’s values. There’s a line where [Thatcher] says: “Everyone now starts by saying ‘I feel that’ instead of ‘I think that’ —I think that’s really going to speak to this generation…The film feels incredibly timely. Do you think the film comments at all on the current cultural or political landscape, whether it’s in America or in Great Britain?

MORGAN: I think there’s a few things. There’s a line when she says: “It used to be about doing something, now it’s about being somebody”—and I think that’s very true now, when I think about our obsession with celebrity and our obsession with fame and our kind of belief that everyone can be a star, that really resonated for me when I was writing it because I think the kind of consensus of an audience who make a decision about whether someone’s brilliant or not, that really stayed with me. Whereas, I think when you look at someone like Margaret Thatcher, what was extraordinary about her life was that she went from nowhere to somewhere, and I think she really did go from believing in something to becoming somebody, inadvertently becoming somebody. So I feel that’s very resonant, and then you know I think the natural swing of the pendulum with any change in government which is what we’ve had in the course of me writing this—it’s gone from a Labour government back to a Conservative government, that’s brought a slew of parallels and similarities for me that really resonates. So you know the huge issues around the Euro at the moment, and the European Union and how us being part of that at the moment with David Cameron, so you of course there are resonances but I think that history’s very extraordinary because it does repeat itself.

You mentioned current obsessions with popular cultural. As a writer, though, are there any things—any themes or issues—that you feel particularly obsessive about? Do you find yourself drawn to certain types of stories or values or themes over again?

MORGAN: Yeah, I mean I think all the work probably has links with sort of… I think in the last couple of years there’s been quite a strong vein about mortality, but I think that slightly happens when you reach your forties or your parents age or you lose a parent as happened in my case, or you become a parent yourself and so you see yourself in the life cycle. I think age is really changing how I write and the themes that I connect with. But there are also things I’m really intrigued about. I’m really—one of the triggers of another film I wrote about—which was Shame, was sort of an obsession with the internet and how obsessive I am to it, and how I feel I consume random bits of ridiculous knowledge all the time. And what’s that doing to my brain and more importantly, how is that affecting the way I interact in the world? And those things are really resonant for me and those things I feel are very new that I’m starting to think about. But I think ideas of loss and power and perhaps being a very powerful woman; I think this is sort of a very feminist film in that way. You know, you have a female writer, a female director and a female actor you can’t really miss out on that opportunity to really sort of think about her on those terms and to realize that what’s really shocking is that there’s still a dearth of female politicians. There are still those inequalities that I think she just—she was quite a phenomena in a way. And I still think she’s quite a phenomena.

And it’s such a feminist film in a really refreshing way. You get a lot of film nowadays that are about these career woman who can’t handle their personal lives and they ultimately have to choose one or another. And I found that this film—while it does discuss sacrifice between work and family—it’s also incredibly respectful of her as someone who was able to do both in some ways.

MORGAN: Well she was an extraordinary. She went to Oxford and that she studied as biochemist and then she studied the law and then she then went into a political life and in that period she also had two children and brought them up. She was a political wife and a mother, and you know she was a huge homemaker and yet she became Prime Minister. She was quite an extraordinary multi-tasker and I think we’re all struggling with multi-tasking and I think we put huge pressure on ourselves. And I think what’s interesting about her is that I don’t think she felt the guilt that I think we feel. I think there’s an inherent guilt that most people feel. The thing I think most women struggle with mostly is feeling guilty.

Do you think that guilt aspect is something that’s a recent phenomenon?

MORGAN: No, I think my mum… My mum worked and she always talked about the guilt she felt when she had to go away with work. I think we’re brought up to believe ourselves to be homemakers and mothers. That was, if not in my upbringing, it was certainly in my mothers. I think what’s fascinating about the generation coming up, and not just the generation of women but also the generation of men who are coming up, and those roles are being reversed. You know I’m in a relationship that, my partner looks after the children when I get up to work. And that’s becoming more normal and it’s not that unusual.

It’s interesting, I’ve read that you’re a big fan of Kramer v. Kramer, and just looking at that versus this [film], they’re very interesting portrayals of women.

MORGAN: I mean that was an extraordinary film. I think it’s a mark of—I think what makes so many actresses careers are the choices they make, and you know the thing about Meryl is that it’s not just one or two films, it’s ten, eleven, twelve more films where you go “Oh she’s in that as well!” And actually I think there is a link that she does go for strong powerful women who have to make huge dramatic choices. So Kramer v. Kramer, the lift scene is still one of the most remarkably painful scenes but brilliantly extraordinary films about when a man gets the custody rights for a child, that’s extraordinary. I mean how ahead of its time is that? And then you look at something like Sophie’s Choice which is about a woman making a heartbreaking choice—her child. You know you could go on and on with her career, and I just think she’s an extraordinary actress who reinvents herself again and again.

And seems to make choices that feel fair and rooted in reality which I think makes this movie.

MORGAN: Well I hope so. I felt a tremendous sense of relief when I knew that Meryl was playing this part because I felt she would bring a kind of integrity and humanity and dignity towards effectively an old lady and it’s hard to get films about old ladies made. And a film about an old lady with Meryl Streep—it may have been the only way it would have gotten made.

Well it’s really crafted in a way where in the first five minutes, you’re immediately endeared to her, but it could be anyone. It could be a woman who was successful who wasn’t necessarily Margaret Thatcher—and it’s a very human story. When you have Shame and this coming out—that’s a lot of pressure.

MORGAN: Very different films

But similar, introspective, really character studies.

MORGAN: Well I hope so. I’m glad you perceived a parallel. I know…(laughs)You couldn’t have brought out two different films in terms of subject matter. But I think that’s what fascinating is that they’re both films with incredibly different directors but I think what absolutely seals them is both stellar performances by both actors. I’ve just been really lucky. I don’t think you get that lucky again.

The Iron Lady, the Pathé film The Weinstein Co. acquired at Cannes last May, opens limited this Friday. Meryl Streep stars as Great Britain’s first female Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, in an emotionally moving and inspiring performance. From the opening scene the film is immediately gripping, with an unexpected narrative. The story glimpses into her political reign--seamlessly intertwining newsreel and rock ballads--but predominantly focuses on Thatcher's older life as she struggles with dementia. The film has many similarities to Weinsten’s pic from last year, The King’s Speech, in that it profiles a public figure, but chooses to spend most of the screen time on their imagined private lives, making for a film that hooks and involves audiences while educating them.

At the press junket, I talked exclusively with writer Abi Morgan, who penned both The Iron Lady and Steve McQueen’s Shame. We talk about why she chose to focus more on Thatcher’s post-political life, the universality of the film, and the themes and stories she’s attracted to as a writer. The Iron Lady opens wide January 13th. Hit the jump for the full interview.

JUMP

I want to ask if you’re struck by how not political it is, and how personal it is. Is that something you do sort of fantasize about—a public figure and what they do in their private time?

ABI MORGAN: Yeah I think… I thought about all those moments where you see iconic political leaders, celebrities, sports stars, and you see them in the moment when they don’t realize they’re being photographed. And those are always the intriguing ones. There was sort of a fascination for me to try and write about… I tried to think about the period when I was reading about her and doing the research, and sort of thinking about her life. And I found the period that was hardest to see record of was the sort of near-present, and so that became very intriguing to me. And then I read a fascinating article by her daughter where she talked about the moment when she realized her mother was suffering from dementia and I felt that as soon as that came out into the public domain, I felt that I really wanted to write about it. I really wanted to write something that would reflect that.

And I think that’s—the dementia aspect—is one of the main things that people are really going to respond to. Whether someone has a family member or they know someone who’s experienced that--

MORGAN: I have dementia in my own family so I recognized that as an experience and I’d observed it but I do think it’s more of a universal story. I don’t think it’s a political film. I think it’s about the study of power and the isolation of power, but that’s also set against the isolation of old age and in particular, the isolation of dementia, in a way. And this is a film really about a character, Margaret Thatcher, who the past sort of attacks her and takes her hostage in a way. And so I tried to use the structure as how someone’s mind is like a flick-hold to memory. You’re trying to grab bits of information and then lose it again. And the kind of nightmare of that experience really resonated with me when I wrote it, and that’s what I sort of focused on.

I know you write several drafts—do you workshop at all?

MORGAN: Sometimes I do, it depends on different projects. I quite often workshop scripts. So you know you’ll sit with the actors and the director just to see how it’s read. But I didn’t with this one, which is interesting. I did lots of drafts. I had done a number of drafts and then Phyllida Lloyd came on as director, and obviously that brought a whole new stage of work. And when you have an actress like Meryl [Streep] who’s such a great interrogator of dramatic arc and character and has, you know, she’s worked on some of my favorite films. I knew that when she spoke, and when she heard a response and thoughts about the character and the screenplay, that they were all really worth listening to. You know most of screenplay writing is deciding which voices you want to listen to and take on board, and hers was the one I really wanted to hear.

I know you’re speaking about voice in a different context, but in terms of Margaret Thatcher’s ‘one-liners’…she has all these sort of interesting expressions or wise words…Is that something you really took from research or is some of that something you were just able to play with and imagine?

MORGAN: I think there are certain things I played with. So the doctor scene, that was an idea…there was a great saying that had been said to me before and I thought, that’s really interesting, I wonder if that would work in the context of the film. It feels so apt for her whole philosophy, so that was something I found, whereas there are other phrases, there are other little things “DT”, or, “another lotion, boss”—the kind of phraseology of Dennis [Thatcher] was very much something that I think resonates if you read his memoirs and if you read the way he’s written about, there is a certain bonhomie to his language that I filtered and put in the script. But often, you know, the process of re-writing and writing and re-writing means that you may have a brilliant phrase, but over time it distills and distorts and changes, and so a lot of it is about the essence of something that she’s said, rather than the literal taking of a quote.

The scene between the doctor is one of the more powerful scenes, and one which seems to really sum-up Margaret Thatcher’s values. There’s a line where [Thatcher] says: “Everyone now starts by saying ‘I feel that’ instead of ‘I think that’ —I think that’s really going to speak to this generation…The film feels incredibly timely. Do you think the film comments at all on the current cultural or political landscape, whether it’s in America or in Great Britain?

MORGAN: I think there’s a few things. There’s a line when she says: “It used to be about doing something, now it’s about being somebody”—and I think that’s very true now, when I think about our obsession with celebrity and our obsession with fame and our kind of belief that everyone can be a star, that really resonated for me when I was writing it because I think the kind of consensus of an audience who make a decision about whether someone’s brilliant or not, that really stayed with me. Whereas, I think when you look at someone like Margaret Thatcher, what was extraordinary about her life was that she went from nowhere to somewhere, and I think she really did go from believing in something to becoming somebody, inadvertently becoming somebody. So I feel that’s very resonant, and then you know I think the natural swing of the pendulum with any change in government which is what we’ve had in the course of me writing this—it’s gone from a Labour government back to a Conservative government, that’s brought a slew of parallels and similarities for me that really resonates. So you know the huge issues around the Euro at the moment, and the European Union and how us being part of that at the moment with David Cameron, so you of course there are resonances but I think that history’s very extraordinary because it does repeat itself.

You mentioned current obsessions with popular cultural. As a writer, though, are there any things—any themes or issues—that you feel particularly obsessive about? Do you find yourself drawn to certain types of stories or values or themes over again?

MORGAN: Yeah, I mean I think all the work probably has links with sort of… I think in the last couple of years there’s been quite a strong vein about mortality, but I think that slightly happens when you reach your forties or your parents age or you lose a parent as happened in my case, or you become a parent yourself and so you see yourself in the life cycle. I think age is really changing how I write and the themes that I connect with. But there are also things I’m really intrigued about. I’m really—one of the triggers of another film I wrote about—which was Shame, was sort of an obsession with the internet and how obsessive I am to it, and how I feel I consume random bits of ridiculous knowledge all the time. And what’s that doing to my brain and more importantly, how is that affecting the way I interact in the world? And those things are really resonant for me and those things I feel are very new that I’m starting to think about. But I think ideas of loss and power and perhaps being a very powerful woman; I think this is sort of a very feminist film in that way. You know, you have a female writer, a female director and a female actor you can’t really miss out on that opportunity to really sort of think about her on those terms and to realize that what’s really shocking is that there’s still a dearth of female politicians. There are still those inequalities that I think she just—she was quite a phenomena in a way. And I still think she’s quite a phenomena.

And it’s such a feminist film in a really refreshing way. You get a lot of film nowadays that are about these career woman who can’t handle their personal lives and they ultimately have to choose one or another. And I found that this film—while it does discuss sacrifice between work and family—it’s also incredibly respectful of her as someone who was able to do both in some ways.

MORGAN: Well she was an extraordinary. She went to Oxford and that she studied as biochemist and then she studied the law and then she then went into a political life and in that period she also had two children and brought them up. She was a political wife and a mother, and you know she was a huge homemaker and yet she became Prime Minister. She was quite an extraordinary multi-tasker and I think we’re all struggling with multi-tasking and I think we put huge pressure on ourselves. And I think what’s interesting about her is that I don’t think she felt the guilt that I think we feel. I think there’s an inherent guilt that most people feel. The thing I think most women struggle with mostly is feeling guilty.

Do you think that guilt aspect is something that’s a recent phenomenon?

MORGAN: No, I think my mum… My mum worked and she always talked about the guilt she felt when she had to go away with work. I think we’re brought up to believe ourselves to be homemakers and mothers. That was, if not in my upbringing, it was certainly in my mothers. I think what’s fascinating about the generation coming up, and not just the generation of women but also the generation of men who are coming up, and those roles are being reversed. You know I’m in a relationship that, my partner looks after the children when I get up to work. And that’s becoming more normal and it’s not that unusual.

It’s interesting, I’ve read that you’re a big fan of Kramer v. Kramer, and just looking at that versus this [film], they’re very interesting portrayals of women.

MORGAN: I mean that was an extraordinary film. I think it’s a mark of—I think what makes so many actresses careers are the choices they make, and you know the thing about Meryl is that it’s not just one or two films, it’s ten, eleven, twelve more films where you go “Oh she’s in that as well!” And actually I think there is a link that she does go for strong powerful women who have to make huge dramatic choices. So Kramer v. Kramer, the lift scene is still one of the most remarkably painful scenes but brilliantly extraordinary films about when a man gets the custody rights for a child, that’s extraordinary. I mean how ahead of its time is that? And then you look at something like Sophie’s Choice which is about a woman making a heartbreaking choice—her child. You know you could go on and on with her career, and I just think she’s an extraordinary actress who reinvents herself again and again.

And seems to make choices that feel fair and rooted in reality which I think makes this movie.

MORGAN: Well I hope so. I felt a tremendous sense of relief when I knew that Meryl was playing this part because I felt she would bring a kind of integrity and humanity and dignity towards effectively an old lady and it’s hard to get films about old ladies made. And a film about an old lady with Meryl Streep—it may have been the only way it would have gotten made.

Well it’s really crafted in a way where in the first five minutes, you’re immediately endeared to her, but it could be anyone. It could be a woman who was successful who wasn’t necessarily Margaret Thatcher—and it’s a very human story. When you have Shame and this coming out—that’s a lot of pressure.

MORGAN: Very different films

But similar, introspective, really character studies.

MORGAN: Well I hope so. I’m glad you perceived a parallel. I know…(laughs)You couldn’t have brought out two different films in terms of subject matter. But I think that’s what fascinating is that they’re both films with incredibly different directors but I think what absolutely seals them is both stellar performances by both actors. I’ve just been really lucky. I don’t think you get that lucky again.