We all know the economy crashed in 2008, but how many of us know why or how? Odds are, if you pulled a random stranger off the street they would struggle to properly define a recession, let alone explain the complex series of events that led to the economic crash – I certainly can't. In a world where economic theories and practices have come to rule so much of our personal lives (looking at you, credit scores) and dominate the sphere of political discourse, it's a bit unnerving when you realize just how little you actually know about what the economy is and how it works. Enter Morgan Spurlock and his production company Cinelan, who have partnered with numerous creative talents and economy experts to present the ambitious short film series We The Economy: 20 Films You Can't Afford to Miss, which addresses complex issues like the struggle to define GDP, how human psychology causes recession, and the ins and outs of just what the hell the economy actually is without being a completely bore. Livened up through performances, animation, dance, and varied cinematic approaches, the filmmakers behind We The Economy have found a way to make these often dull and confusing subjects accessible and entertaining to a wide audience.

In anticipation of the film series' release I recently joined a number of other journalists for an interview with Adam McKay, director of The Unbelievably Sweet Alpacas, Miao Wang, director of Made by China in America, and producer Damon Smith. They talked about the genesis of the project, what inspired them about their subjects, what they hope audiences get out of the project, and a lot more. Check out what they had to say after the jump.

Question: Talk about the genesis of all of this coming together and how the project got started.

DAMON SMITH: Last year I think Paul Allen had the notion that people in this country didn’t really have a very good understanding of the US economy and he kind of wondered why. Why not? And what can we do about it. So he reached out to my partner at Cinelan, Morgan Spurlock, and said, “Why don't we make a film that I will help you produce around explaining basic economics to a general audience.” And Morgan said, “That is a brilliant idea, but why don't we do it as a film series, invite lots of filmmakers and directors into the process, and actually tell stories that are not too much like vitamins and vegetables, that are fun, entertaining, and creative. And that are short so we can distribute them online and really maximize the reach.”

What was the process of finding all these directors and figuring out who was going to cover what subject?

SMITH: Well it was a little messy. We had some initial thoughts on who we wanted to reach out to and we were keen on getting narrative filmmakers as well as documentary filmmakers in the mix, and we had a list of story topics. The first thing that we did was the intital group of filmmakers that we reached out to. We simply said, “What are you interested in? What here on this list is something that you're responding to and think you can devise a story around?” Then over the course of the next couple of months, it was a matter of what's left on the list and who can commit during this very short time frame? So we reached out to a lot of people and fortunately almost all of them were able to do it.

What kind of guidelines did you have? Did you have any stringent rules about the length or the medium?

SMITH: The big rule was the format obviously, which was five to eight minutes. So we very much wanted to keep it in that time frame because we know that that content, that short form, really performs well online and when you go over about seven or eight minutes the attention span drops away and people aren’t going to share something that long. That was the main thing. Everything else was up to the filmmakers. It was their creative brainchild, whatever they wanted to do, how they wanted to approach it, whether they wanted to script something or whether they wanted to shoot a documentary, we left that entirely up to them.

Did you only go out to the lefties?

SMITH: Of course [laughs]. It's funny you say that because one of the documentary filmmakers always jokes about the fact that all documentary filmmakers are communist. How to you navigate that?

ADAM MCKAY: Waiting for Superman was right-wing, right? There's something. They were great with giving us lots of rope and lots of lead as far as the creative end of it went. It felt very loose and fun and free. The only thing was we had the advisers, so we had to have certain information get in, but the experience of it was really great.

As filmmakers, when you have all that freedom how do you chose what direction to go creatively? Adam in particular, how did you end up with Alpacas? What led you to the alpacas?

MCKAY: [Laughs] I think my daughter was watching My Little Pony non-stop, she got addicted to it. So it was in our house constantly and its optimism was so funny to me. It was just so beamingly positive, and when you think of income inequality it's like the exact opposite of that, so I was kind of drawn to that right away.

The Lollinator 5000, why is 5000 always the funniest number?

MCKAY: It's kind of true, right? 1000 doesn't quite get you there. You figure 1000 is the first generation. They don't even do 1000s anymore. It's 2.0 or 3.0. I think anytime you're in that cartoon land, you instantly go back to that old language. It's very Flintstones like terminology.

Have you done animation before?

MCKAY: You know, I think the only other thing I've done is that I collaborated with Robert Smigle on TV Fun House when I was on Saturday Night Live, so I've written a couple of those with him or for him, but I definitely love it in the sense that you storyboard it and then other people go do all the work, and then it comes back you you and you just go, “This is good. This isn't good. Fix this.” And Six Point Harness, which is who we made it with, was so amazing and so collaborative that it just made it a blast. Yeah, I could see how people get addicted to animation, and I understand why it's so great for comedy. You can do whatever you want and it just happens.

Did the animators put in the herbs and spices, or were you being very specific and telling them what you wanted in the background?

MCKAY: A little bit of both. Yeah, they usually throw a bunch of stuff at you and you said yes or no to it and then you add to it. So in the script a bunch of it's obviously written, but for instance when they go to the executive lounge, you see where the executives are, and I said, “Why don't you add a massage table and a sushi bar?” You add all this stuff. Then when they show her dad I was like, “Give him an Ayn Rand book in his hand.” The Koep brothers’ father is kind of the vibe of that, so you're adding those kinds of details, but part of the fun for the animators is they get to suggest stuff as well.

It's pretty ironic that you've got this animation industry that's moving to Vancouver and Canada now-

MCKAY: Yeah, and Asia too.

Right exactly. And here you are something on the economy. Did you tap into local talent?

MCKAY: Yeah, this was all done locally. Six Point Harness is based in LA, so they did it all here. But I mean everything is leaving. Even with the film industry, it goes to other states. TV seems to be the one that is really staying put. Did someone do outsourcing as a subject? They must have, right?

SMITH: Yes, Albert Hughes did a film called City on the Rise, which he went to Detroit to shoot.

MCKAY: Oh, I got to watch that.

SMITH: It's beautiful.

MCKAY: You're right. Most of the animation is leaving, yeah.

Was there any one particular short that really impressed you when you saw?

SMITH: Miss Wang's film had that effect on me. Yeah, because she was given a very difficult task, which was to engage with the story of China's economic rise, but to look at it from a very different perspective. This is a story about the US economy, so we didn’t want a piece about China's economy, we wanted a piece on how China's economic boon has had an impact, positive or negative, here in the states. And what she came back with, first in treatment form in terms of what she wanted to do and the story she wanted to tell, was a huge eye opener.

MIAO WANG: Yeah, and I was telling a story about South Carolina, so...[laughs]. But it was interesting because when I first talking to the economic advisers they were also actually interested, they were like, “what's going on in China is interesting.” And I was like, “no, I’m focusing on what's going on in the US, how it's impacting the US.” And then just realizing from my research as well that, as we're seeing, some of that is actually coming back here. My whole story is kind of about the globalization 2.0, which is that Chinese companies are now investing here. That's how far the Chinese economy has grown in some ways and how integrated everything. That's a story a lot of people haven't really become aware of.

MCKAY: It's a beautiful film.

WANG: Thank you.

As a filmmaker were you salivating when you got the country hicks with the thick southern accents? Did you love that?

WANG: [Laughs] I did. It's funny, Robert, our editor, he actually came from that region and he was like, “I'm jut going to tell you some of these things that this person is saying, you might not realize that it's racist, or that it's this and that, so I'm going to be your filter a little bit.” Because I didn't want it to be stereotyping anybody, you know? It was pretty fascinating, just what people were saying on the street. That was actually really interesting for me, because I've actually never been to South Carolina, so that was a little adventure. I was like, “I'm just going to be back here.” And I had someone else do the street interviews.

Where did you go in South Carolina?

WANG: All over, actually. We were in Charleston briefly. We were in – they call it Uphill Country - where all the textile mills are, but that was fascinating, because we found this one retired worker, who became a very central character in our story. And he's someone who really went through the entire collapse of the textile mill industry in South Carolina that all went to China, but what he said and just how he felt about it was so amazing and eye opening. He actually was like, “I'd love to go into this factor that a Chinese company opens here.”

How long did it take for both of you to put your films together from beginning to end?

MCKAY: What were we? About two months, I think that was our time. It wasn’t' so long. It was animated, so we took an easier road than you. [Laughs] We didn't have to go to South Carolina. All the praise and kudos to the documentary filmmaker. Yeah, I just sat in my office here in LA and looked at storyboards.

WANG: I spent a very concentrated period of time doing research doing some research and then just really coming up with the idea of doing this story, setting it in South Carolina, and focusing it on that. The mill story, And we got fairly lucky for a documentary it's so important to find the characters and to find people who will give you access to film, so usually that process takes a lot longer and that was really a major part of my worry in the beginning. How am I going to go out and in a month or less, a couple weeks really, to find all these people? We did get fairly lucky with that. It was about a month and a half, I would say.

Can we trust the Chinese? They seem like a kind of a bigger walmart, and WalMart is kind of like a Ted Bundy, they lour you in with a charm and then take you out. Like if you're a distributor. “We'd like to order a hundred thousand of your little pencil sharpeners, but you're going to have to lower the price.”

WANG: But WalMart is also doing that because the American consumer, it's supply and demand right? It's not like they're creating the – they're kind of fueling it. The American consumer is like, “I don't want to spend that much money on a pair of glasses.”

MCKAY: I always say the Americans have traded our entire manufacturing base for 20% off on oscillating fans. [Laughs] Yeah, well their growth is flat right now. They're hurting. They actually just announced they're going to be increasing minimum wage, because it doesn't work.

WANG: They also have an initiative, they call it the “Made in America” initiative I think, to actually bring back-

MCKAY: It's a little bogus though.

WANG: It is a little bogus. I went to one of the factories that does that, and basically everything is really made in China and they just bring everything in a box that's practically all together, and they take it out of the box and they assemble it. So it's called “Assembled in the USA”

MCKAY: And they also count groceries as part of their sales, and groceries have to be...so it's totally bogus. But they're hurting, man, they're growth has flattened. Treating your employees like crap doesn't work, like McDonalds and Burger King. One of the fun things about doing this was I got to hang out with Adam Davidson, who was one of the consultants, and we just got to talk and talk. He turned me on to all these great books. I'm also adapting The Big Short, the Michael Lewis book, on a separate project, so he turned me onto this book “The Good Job Strategy”, which talks about how it's actually bad business to treat your employees like crap and to have low-grade quality and everyone seems to be getting kind of hip to it. For Walmart to give up on minimum wage is shocking – if they really do it. Who knows? It could be a fake press release. I don’t trust WalMart.

WANG: That was another interesting thing I learned form this whole process is that actually the companies – just in general foreign invested companies who come to America to start a company, to open a manufacturing business or whatnot, they actually provide much higher wages than American companies.

MCKAY: Yeah. Right? Toyota, when they opened their factories here they paid higher.

WANG: Yeah, it makes sense, because if they're going to make the effort to come to a different place that’s all foreign to them you would think they would at least try to succeed.

MCKAY: Well their wages are rising as well right?

WANG: Yeah, their wages are rising. There's many reasons why Chinese companies are coming here because wages in China – it's fascinating, it was like 12-1 before and in the next couple years it will be 3-1.

MCKAY: Wow, really?

WANG: The gap, the wage gap, is decreasing rapidly. So there's a lot of factories that are...you know, with the cost of transportation, and land cost and energy costs are apparently much cheaper in the United States.

MCKAY: And their consumer base is here.

WANG: Exactly, if they're making it here already they won't have to ship it. In terms of the textile, they have a ready made history of textile in South Carolina.

Someday Apple may make stuff here or Nike.

WANG: It's very possible.

MCKAY: Nike's the one. Like, come one, one factory.

Was there any interaction between the filmmakers while they were making their projects? Any friendly competition?

MCKAY: No?

WANG: No, I didn't know really.

MCKAY: You would tell us what different people were doing when we selected our topic and then out of curiosity I would ask what people were doing, but the idea was that each one would be it's own little island.

SMITH: I think you and Chris [Henchy] were probably the closest in terms of filmmakers dialoging with each other.

MCKAY: Yeah, I co-wrote the one that Chris Henchy directed with Adam Davidson about how you measure the economy, so that actually was kind of a collaboration, but otherwise, no.

Did the process change any one of your outlooks towards economics? Did you start with one idea and then during the course of making your films adopt a new outlook?

MCKAY: It sounds like yours did for sure, right?

WANG: Yeah, at least, I mean, I'm not an economic expert, but I do follow the news and just that story in terms of the manufacturing business coming back. I was a little bit aware of that, but I didn't realize that they were investing and building factories here. That was surprising to me.

Do you think the South Carolinians, once they've seen the finished product, may change their perspective on the economy and how it affects them?

WANG: Yeah, that was fun just being on the street just asking people at first, “What do you think of China?” And they were like, “They took our jobs away.” But then when we talked and said, “What if they come and invest in a company here? What if they're actually providing jobs here?” And they're like, “That would be great!”

You talked earlier about making it accessible for the average person.

WANG: Yeah, that was important.

What are the challenges of getting the guy who may give this a shot in looking at it and taking a look at it, but he's your normal nine to five, watches ESPN when he gets home, doesn't delve into sobering matters like this. What do you guys have to do to make it accessible to that kind of person?

SMITH: I think comedy is absolute gold, so there's a lot of comedy in the series. If you make people you can make people learn. Also, anything that's visually striking that really grabs your attention and fires into your brain, “Wow that's an amazing magnificently beautiful image I'm looking at, you just engage more closely with it. So we have an Albert Hughes film that's visually stunning. We have Lee Hirshe's film that he did with Polabolis, which is absolutely incredible.

Recession?

SMITH: Recession, that's right. So that’s it. Comedy is king. I really believe that. And ususlly beautiful artistic work. Miao's DP did beautiful work on the China film. You will watch it more intensely and think about things that are happening on screen if your brain is pleased.

Is there ever a tough line to walk in that you want to make it accessible and entertaining, but keep the integrity of the content?

SMITH: Absolutely. That was the whole process of filmmakers talking to advisers and I think Adam can probably speak to that.

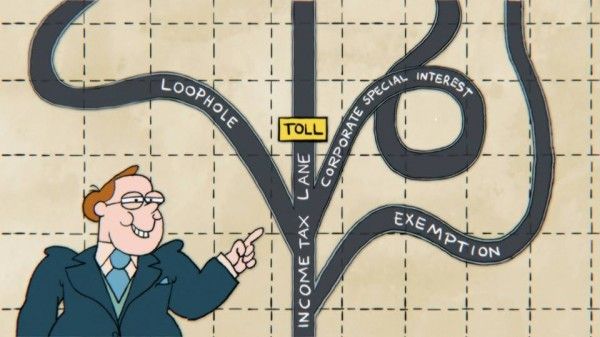

MCKAY: Yeah, we had that. Because I knew that if I had just written a funny six minute short using a parody of My Little Pony that touched upon income inequality we could do a really crazy funny short, but it wasn't the entire goal of it. The goal was to also inform, so there was this balance between how informational we would get in certain areas and then go for a little bit of a laugh and rely on the visual style. All the movies that I do outside anyway always deal with – Anchorman, as silly as it is, is also about the total failure of journalism in our country. That's usually what we do anyway, but we never get this specific. That's what was unusual about this, where we're actually saying numbers about income distribution, wealth distribution and how to put that in there in a way that's still playing in an entertaining way. It was unusual. I'd never done anything that had this kind of responsibility to be informative. Adam Davidson, who was my adviser, and I definitely had a couple arguments about it – one argument – about how do you do this? I wanted to say this one line because it was more pithy, but he said it wasn’t entirely accurate, so we had to make it more accurate, but then it wasn't as funny. Then I'd go fact check him and go, “Wait a minute, this happened!” And he's go, “Yeah, but that's only here, so we'd have to go back and forth trying to find the accurate, funny line. It was really cool.

You asked how did it change our opinions. There were a couple things. I always knew that – obviously, I have certain beliefs about how people should treat employees and how companies should be run, but I was really surprised though this process to learn that those beliefs are actually good business. I didn't know any of that. When I read The Good Job Strategy I was surprised. Like, oh my god, this actually is more profitable. What Costco is doing is a smarter way to run a business. So that was cool, to not just have it be a belief, by the end of it to have it backed up by statistics. Even Davidson, who's very moderate, almost conservative, even he at the end of the day had to admit, “Yeah, there's no reason minimum wage shouldn't be higher.” He really couldn't tell me one reason. He'd be mad that I just said that, but I asked him from twenty different directions and he was like, “[Sighs] It should probably be higher.” He hates to just give answers, “It depends what case you're talking about...” But yeah, I really loved it and it just led me to read five or six books I wouldn't have read. I had a great time. But yeah, information, specific numbers and comedy are hardly friends. In documentaries too, you want it to be the person...

WANG: Exactly, yeah. This film is actually not something I do in my documentaries, because I want to do more verite and follow just the character and focus the story on the human character, and this one I felt like I had to balance that a little bit.

When you think about the average Joe we talked about earlier, what's the hope for what he does with this new information?

SMITH: They can speak specifically to their films, but I think the goal is really to enlighten people so that they're better informed about something that we all frankly should have learned in high school at the very least along with law. I think that if we can get people curious and interested ahead of the midterm elections and we go into the election cycle and the noise around the economy starts to heat up, then people have a way to engage with it that they didn’t before. They might know something more about minimum wage and how that works, globalization and trade, all these different issues that people are constantly screaming at us about, and we don't even know how to find our compass.

When it comes to marketing this and getting people to watch it knowing that that type of person is my audience, we lefties can be accused of being a bit condescending at times. How do you draw people in without making them feel like you've had to dumb this down for them to consume it?

SMITH: I don't think that I'm concerned about that. I think the films speak for themselves. They're editorially sound and grounded and absolutely fun, entertaining, and at the very least informative in some way. I really think people will find their way to it organically. I think there's going to be a big push and a lot of attention immediately around the launch, but then I think the films are going to travel individually online, and organically communities will find their way to a piece that speaks to them about issues that are important.

As a parent I’m so happy, because I have thirteen year old stepdaughters who I can sit down and show [Adam's] film and they’re going to laugh and then they're going to ask me questions. Then I have older sons who didn't learn any economics in high school, and everyone's on their phone.

MCKAY: My daughters watched the short and then had questions about it, and even my wife didn’t know some of the numbers that were in it. That is the dream response. Then if people can start asking the question – why aren’t we teaching economics in high school? Why isn’t there law taught in high school? It's actually crazy that it's not. And if those provocative conversations going, “Why isn't this taught?” That would be the dream outcome.

WANG: Hopefully also a lot of the films will open – you want to learn more about that topic, because it's really so little room to say...there's so much more they could go find out about.

SMITH: Have a spin around the website and the mobile app and see all the resources and discussion guides and lesson plans that we've put together to complement the series, because it's really something that we want people to explore and be aware of.