There’s a sense of inevitability to Air Force One. In the years since Die Hard struck box office gold, Hollywood had obsessively depicted the hijacking of buildings and vehicles with lone heroes saving the day. It was only a matter of time before the world’s most famous aircraft was taken, and the world’s most powerful man got to neutralize bad guys with a machine gun. But once you’ve shown the President of the United States kicking a terrorist off the back of a plane, where to next?

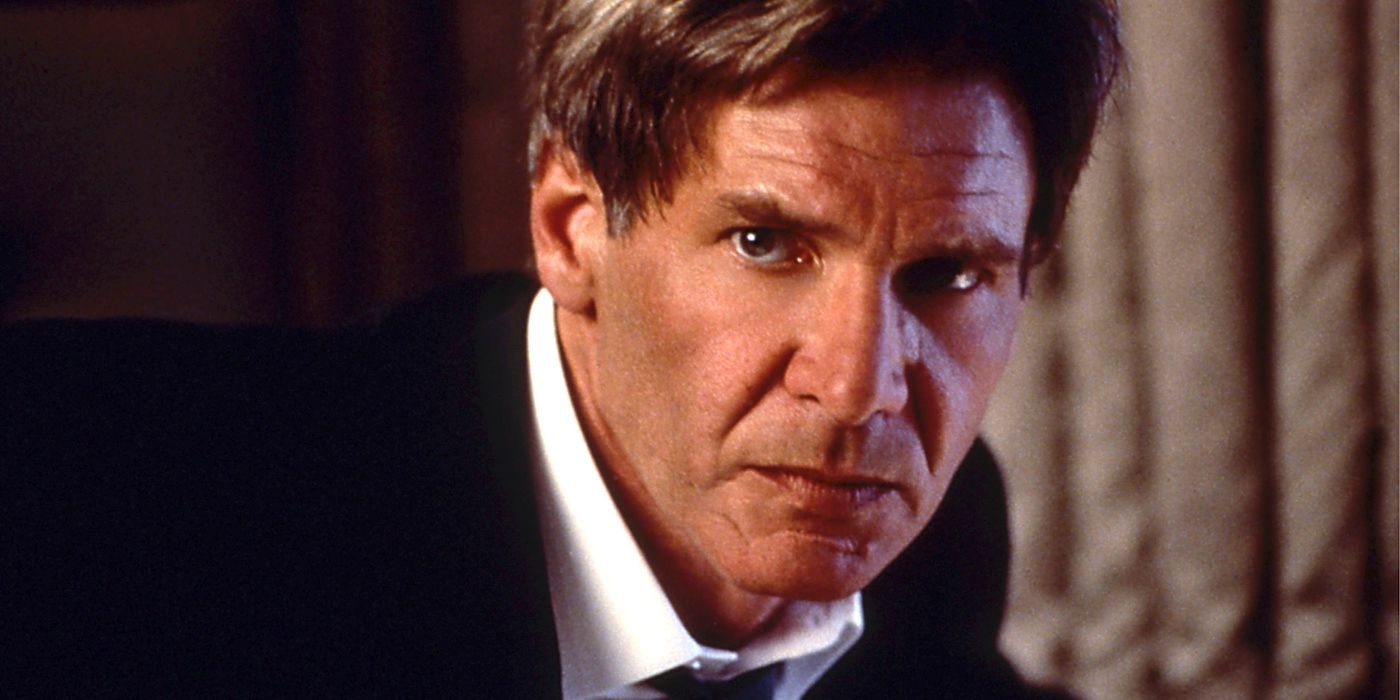

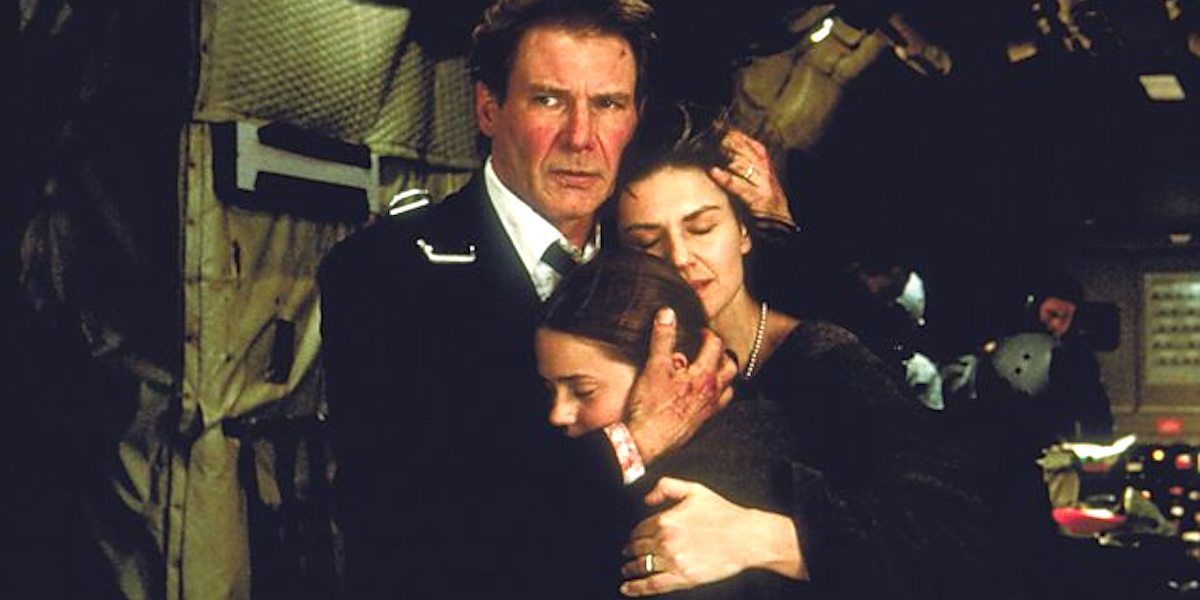

When terrorists seize Air Force One, it falls to President James Marshall (Harrison Ford) to regain control of the plane. Marshall must ultimately decide whether he will negotiate with the radical Ivan Korshunov (Gary Oldman) when his family is threatened.

“Harrison Ford is the President of the United States,” declared the poster for Air Force One. In 1997, with an already scandal-prone Clinton presidency and the optimism from the fall of the Soviet Union slowly dulling, that sounded like a very attractive proposition. '90s cinema had a bit of thing with the White House, whether re-imagining the Kennedy years or depicting a more idealistic president for the time. Independence Day’s President Whitmore (Bill Pullman) is a former fighter pilot and upstanding family man who finds the courage to rally a nation. In Dave and The American President the man in the Oval Office chooses authenticity over political maneuvering – the latter film, written by Aaron Sorkin, anticipates the idealized President Bartlet (Martin Sheen) from The West Wing.

President Marshall is cut from the same cloth, not least because he’s another middle-aged man with a paternalistic name (although Michael Douglas’ President Shepherd takes the award for most metaphorical moniker from these films). We first meet Marshall delivering an impassioned and improvised speech, addressing a concern of the time that leaders were increasingly controlled by their spin doctors. He shows an exasperation with the political machinations of his advisers – they mainly seem annoyed because he speaks out against terrorism. For a moment, with the delayed introduction of his wife (Wendy Crewson) and daughter (Liesel Matthews), there’s an anticipation of some friction (as in Dave). However, Marshall is adored by his family, the only source of disagreement being a refusal to let his twelve-year-old daughter visit a refugee camp. The introduction of his press secretary could have been the cue for some Clintonesque shenanigans, but Marshall is only interested in watching the ball game.

After a fast-paced SEAL mission, Air Force One’s opening is as stately as a White House dinner. Marshall is thoroughly decent (and dare one say, boring) in the manner of Jack Ryan, Ford’s other big role of the decade. Similar movies, most notably Die Hard, pile on the family and situational tension in the first act. Even heroic President Whitmore in Independence Day is granted some personal issues to overcome – although a veteran, he's initially seen as a weak leader. However, Marshall is accepted by the military brass and his advisors from the outset, someone who has managed to parse his war experience into political action. The script shies away from character development, although it's clear Marshall's politics are going to be challenged in a very personal hostage situation.

When the inevitable takeover occurs, it’s a mad scramble with automatic rifles being liberally fired in the pressurized cabin. That the plane doesn’t blow up at that point alone strains credulity. Nevertheless, the ensuing sequence of Korshunov’s men battling for control as the pilots try to land is one of the 90s' most exciting action scenes – a 10-minute burst of adrenaline that's an all time great piece of plane-based mayhem. The President is missing in action at this stage, suggesting that he took an escape pod like Donald Pleasance’s weasel Commander-in-Chief in Escape from New York. Of course, Marshall has decided to stay on board (the red herring about marines retrieving him from the pod fooling no-one). Had he bailed, Air Force One would have been a very different movie.

Air Force One follows a path that was well-worn by the time of its release. Die Hard established an action formula in 1988 that incorporated elements of the dormant disaster movie genre: lots of crawling through tunnels, hazardous environments, and a cat and mouse game with the bad guy. Following Alan Rickman’s brilliant turn as Hans Gruber, the villain was often played by a British actor, with Jeremy Irons, Charles Dance, and David Suchet all giving bows in the following years. They were frequently quasi-terrorists – using ideology as cover for an elaborate heist. Genuinely unhinged individuals were more often played by American actors like Dennis Hopper or Willem Dafoe. This parade of bad guys would hijack anything, from airports to cruise liners – even a mountain (sort of) in 1993’s Cliffhanger, a film featuring American John Lithgow as a British nasty by way of mixing things up.

Part of the winning formula involved the meticulous unfolding of “the plan,” from Gruber’s clinical takeover of Nakatomi Tower to the slow build of the bomb on the bus in Speed. There were plenty of second tier characters in danger (common to the disaster movie genre) although the hero would have a family member or fast friend to worry about more personally. As in Air Force One, the hero typically undertakes a sneaking mission in the second act, picking off a few heavies before the lead bad guy gets wise. Then it’s a more direct game of blowing up lots of stuff and loved ones having guns pointed against their heads.

Popularized via imitators such as Passenger 57 and Under Siege, the phrase “It’s Die Hard on a (insert name of vehicle)” became shorthand for the high concept nature of these films. Of them all, Speed (directed by Die Hard cinematographer Jan de Bont) was the most propulsive, fully capitalizing on the elements of extreme destruction and a battle of wits. However, by 1997 the genre was showing signs of fatigue. There had been flops such as Under Siege 2: Dark Territory (Die Hard on a train), and a big one on the horizon with Speed 2: Cruise Control (Die Hard on a cruise ship). The problem was clear: filmmakers were running out of interesting locations and vehicles. Speed 2 epitomized the issue, by setting an action movie all about motion on a slow-moving vessel in the middle of the sea. It was the same dilemma that led to the downfall of the original disaster movie phase in the 70s – there’s a finite number of natural disasters and accidents before the genre starts to collapse in on itself. A 90s revival of straight disaster movies that included de Bont’s Twister and a couple of volcanoes didn't go very far.

Air Force One therefore represents both the pinnacle of the action-disaster movies and a leave-taking. Its great location is also its biggest liability. We get to see the President in jeopardy, using his own two hands to dispatch “Russian ultra-nationalist radicals” (as they’re described in the film’s take on Yeltsin-era issues). However, Marshall spends the majority of the second act sneaking around the baggage compartment, confined by the limitations of the plane. Ford brings all the exasperated charisma he displayed through the 90s, although he doesn’t convince in the fisticuffs against twentysomethings in combat gear. This type of film would not attract a star of his stature again.

Director Wolfgang Petersen had form with both claustrophobic thrillers (Das Boot) and presidential intrigue (In the Line of Fire), but compared to the new wave of gonzo action thrillers like Con Air and Face/Off the film looks positively sedate. Certain set-ups, such as the terrorists grabbing the “nuclear football” from a Secret Service agent, are cursorily dismissed – as if some thriller angles were blunted to focus more on Marshall. Scenes of the Vice President (Glenn Close) and the Defense Secretary (Dean Stockwell) debating the constitution don’t add much tension, aside from the question of why they don’t call in a professional hostage negotiator.

The film’s big moment comes when Marshall meets Korshunov and there’s a reckoning for his “tough on terrorism” stance with his daughter under threat. It’s a scene that’s particularly well-played by Ford and Oldman, with a good deal more emotion than is common for the wordy confrontations of the genre. “Get off my plane!” may be the film’s most famous line, but it’s most honest is, “Leave my family alone.” Oldman’s villain seemed like a pantomime performance at the time of release, part of the 90s action movie tendency (also in Crimson Tide and Goldeneye) to invoke a Soviet resurgence as an excuse for ongoing Cold War tensions. However, it’s a portrayal that looks more believable with the benefit of hindsight, especially regarding the end of the decade and more recent events.

Air Force One culminates with the disaster movie staple of a crashing plane and Marshall getting advice on how to fly it via a headset, followed by a far-fetched rescue that proves CGI in the 90s only really did dinosaurs well. The film was incredibly successful (the fourth highest grossing movie of the year) but it drove a nail into the coffin of this type of adventure as much as the flops. It was a peak experience, containing every genre element developed over a decade, yet somehow never reaching the heights of Die Hard or Speed. Audiences would ultimately look to more bombastic thrills for a time (such as the disaster sci-fi Armageddon) and then more realistic action movies with the turmoil of the early 2000s, when terrorism took on a different specter.