There’s absolutely nothing that Hollywood loves more than reboots, remakes, and reimaginings. In an era where intellectual property is the key to studios’ success, producers are often keen to rework popular classics for an audience of a different generation. Oliver Hermanus’ new film Living draws from one of the most beloved films of all-time: Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru. The 1952 classic stars Takashi Shimura as an older man coping with his impending death. Ikiru is widely considered to be one of the pinnacle achievements of Kurosawa’s career, and was recently included on the Sight & Sound directors poll of the 100 greatest films of all-time.

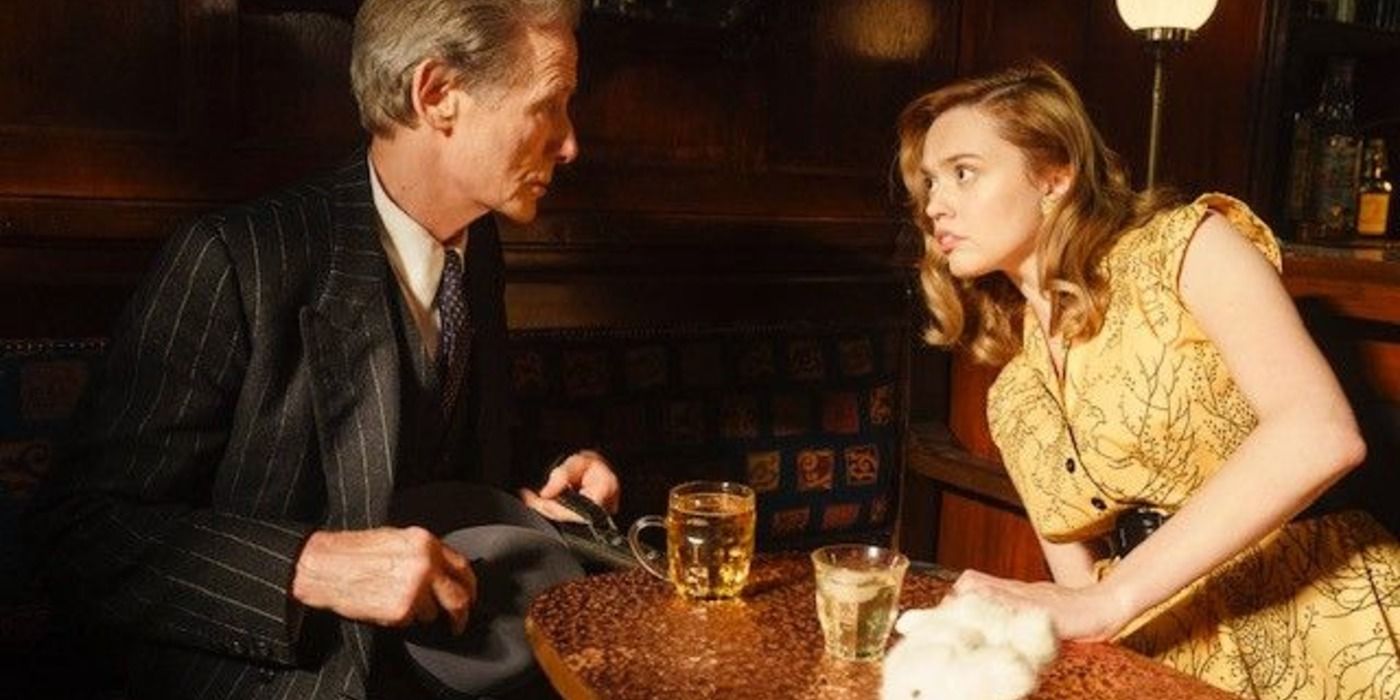

Living explores a similar story, but it takes place in London during the 1950s. Bill Nighy gives a career-defining performance as Mr. Williams, an aging working man whose illness causes him to begin living life to its fullest once more. Determined to be remembered past his death, Mr. Williams begins talking with young people, and taking on new experiences during the last days of his life. While it’s a heartbreaking film, Living is empowering in how it celebrates autonomy. Nighy is widely considered to be among the front runners for this year’s Academy Award race for Best Actor, as he’s shockingly never been nominated previously.

There’s an inherent danger with any remake, particularly one that adapts a story that was originally intended for audiences of a different country. English-language remakes of international films often go horribly awry; Spike Lee’s remake of Park Chan-woo’s Oldboy was a laughable attempt at pulling off the original film’s impact, and the live-action reimagining of Ghost in the Shell attracted controversy over its whitewashing of the original source material. However, Living isn’t a story that belongs to just one culture; like many Kurosawa classics, it speaks to a universal message that is comparable to mythology. The power of Kurosawa’s classic films have inspired English-language filmmakers for decades, and the ramifications of his influence can still be felt today.

Why 'Living' Works

As evidenced by Disney’s live-action remakes of animated classics, there’s simply no creative point to recreating something shot-for-shot. If something is already iconic, seeing it again has no staying power. However, Living doesn’t attempt to recreate every single moment from Ikiru. It’s actually a much tighter story; Living is just over 102 minutes, while Ikiru is almost two and a half hours long. Living actually gets back to the source material; Ikiru was originally inspired by the classic Russian novel The Death of Ivan Ilyich by Leo Tolstoy. The Death of Ivan Illyich is taught in schools to this day because of its ability to pack so much thematic resonance within a tight page count.

While a remake like Ghost in the Shell is rightfully accused of cultural appropriation, Living does not attempt to reimagine any of the traditions surrounding death and the afterlife that are specific to Japanese culture. Death, illness, and the elderly are treated differently in the British culture of the 1950s, and Living is intertwined with moments specific to Mr. Williams’ worldview. Ikiru is praised for its celebration of the Japanese way-of-life, and there are similar homages to London’s culture in Living. There’s a particularly amusing scene where Mr. Williams takes a break from his working life to go to a rowdy bar and sing karaoke.

However, Living has a similar value to English-speaking audiences as Ikiru did for the Japanese film community. Similar to how Takashi Shimura was given the role of his career, Nighy takes the rare chance to play the lead. He’s easily one of the best character actors of the last several decades, but it’s rare to see him as the definitive leading man. While the film shows a similarity to its predecessor with the way that Mr. Williams gives back to his community, it’s taken in a different direction as he escapes his dehumanizing daily routine as an accountant to contribute to a local park bench.

Living also benefits from gorgeous production design that serves as an alternate, but not a rebuff, of Ikiru. While Ikiru was contemporary at the time of its release, Living is a period piece that reimagines the 1950s from a reflective point-of-view. The intentionality is clear; it underscores the parallels between the two nations in the aftermath of World War II. Both countries are healing, and Living shows how similar they really are. It’s a work of empathy. This is seen in the similar final moments of Mr. Williams on a swing, which tastefully reinterprets the similarly iconic moment in Ikiru.

A History Of Influence

Ikiru is among the best, but certainly not the first English-language remake of a Kurosawa classic. In the 1960s, filmmakers realized that Kurosawa’s samurai films could be easily reworked into Westerns. The result was some of the best Westerns of all-time, as these English-language remakes took on totally different tones. Yojimbo, Kuroswa’s elegant action classic, was remade into the outrageous spaghetti western Django, which birthed a franchise.

Among the most popular of Kurosawa’s films is Seven Samurai, which is widely considered to be his masterpiece, and was recently ranked 20th on the Sight and Sound critics poll of the greatest films ever made. Famously, Seven Samurai was remade in 1960 as The Magnificent Seven, one of the most enjoyable adventure films of the era. While Seven Samurai is an epic that contemplates the nature of heroism, The Magnificent Seven is just a playful, action-packed blast. Seven Samurai’s score from Fumio Hayasaka is quite profound, but The Magnificent Seven’s playful theme by Elmer Bernstein is iconic in its own right. The Magnificent Seven became such a sensation on its own that it even inspired another remake in 2016 from Antoine Fuqua.

Beyond these iconic favorites, Sanjuro, Stray Dog, Sanshiro Sugata, Kagemusha, and High and Low have also been remade. That’s not even considering the sheer amount of films that drew inspiration from Kurosawa’s game changing techniques. The Hidden Fortress is one of the major influences behind Star Wars, and it's easy to trace Quentin Tarantino’s use of flashbacks to Rashomon.

Kurosawa’s films are transcendent, and their remakes don’t diminish their value in any way. Hopefully, films as excellent as Living will inspire some younger viewers to check out some of the Kurosawa classics that they may have missed. There’s a universal power to his stories that give them value beyond any specific cultural nuances.