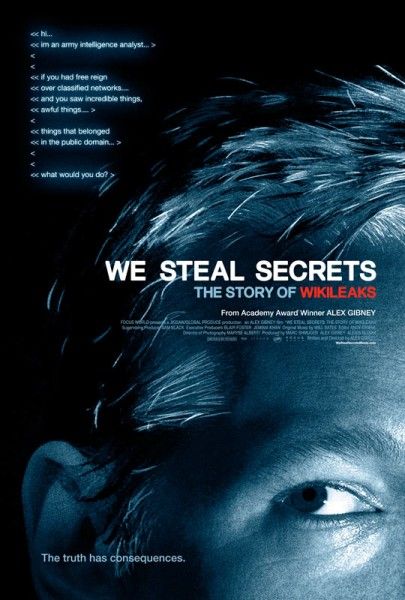

Academy Award-winning director Alex Gibney’s We Steal Secrets: The Story of WikiLeaks is a riveting, multi-layered tale about transparency in the information age and our ever-elusive search for the truth. Unfolding like an exciting political spy thriller with a cast of complex characters, the film confirms that real life is often more compelling than fiction as it chronicles the creation of Julian Assange’s controversial website which facilitated the largest security breach in U.S. history. The enigmatic Assange’s rise and fall are paralleled with that of PFC Bradley Manning, the brilliant, troubled young soldier who was the source of all the documents that WikiLeaks is famous for.

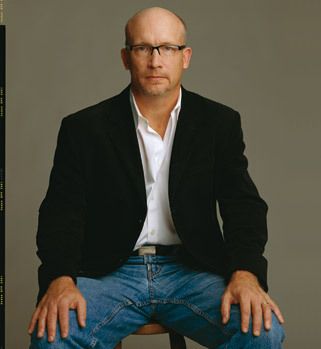

In this exclusive interview, Gibney talked to me about his reasons for doing the film and how they evolved as he learned more, his impressions of Assange, why Manning was central to the story, how not being able to interview the two key players led to a more powerful film, the challenge of making a documentary that appeals to both men’s supporters and detractors, his response to Oliver Stone’s criticism, his thoughts about the role of media, transparency and the issue of privacy in the internet age, and his upcoming documentary, Lance Armstrong: The Road Back. Hit the jump to read more:

Question: What appealed to you about this project and made you think this would make a fascinating film?

Alex Gibney: Two things. One was I thought it was an incredible David and Goliath story in the age of the internet. And two, I initially thought it was a story about a fascinating new technology, this idea of the leaking machine. So that’s what originally motivated me. My reasons for doing the film changed as I learned more about the story.

This movie tells a very complex story populated by unusual characters with great strengths and weaknesses. What was the most surprising thing you discovered?

Gibney: Bradley Manning. When I first started the story, I thought it was a story about Julian Assange and I realized that I was missing one of the main characters. He had been written out of the story. So, the discovery of Bradley Manning and figuring out how to include him in the story was the biggest surprise for me, because I had no idea I was going to take that on when I started.

How did you gain access to the key players and get them to open up and reveal so much?

Gibney: Well, I clearly failed when it came to Julian Assange. But in terms of the others, it was just a process of reaching out and hoping, letting them know about my previous work, and letting them know that their testimony would be fairly treated.

What are your impressions of Julian Assange based on what you discovered in the course of making this film?

Gibney: In many ways, I’m a big admirer still of Julian Assange. He had balls to do what he did and his motivations in terms of holding the powerful to account are tremendously inspiring to me even today. But, I feel that Julian Assange came to be both paranoid and self-regarding in ways that ultimately undermined his own mission. And so, the transparency radical became a secret keeper instead of a secret leaker. And that, I think, is a big problem.

What are your thoughts on Bradley Manning? Until now, he’s been the lesser-known story. Did he fall victim to the same kind of callous treatment he sought to expose?

Gibney: He did. I mean, he’s been very badly treated and it’s been really an outrage. It’s fair to say that what was done to Bradley Manning is outrageous. It was done, I think, very purposefully. The Obama administration and the military went after him and went after him hard. Why? Because he was weak. They knew they could get away with it. He’s not well connected. I felt they could marginalize him. And also, I think they wanted to make an example of him. Because of his enormous leak, they were going to show people just how people like that are treated. And frankly, I think they were also trying to muscle him to roll over on Julian Assange. So, he was abysmally treated. Torture is a fair and accurate description, I think, of what he endured.

Was it a challenge to tell this story without being able to interview two key players or did it lead to a more powerful film?

Gibney: I can imagine what the other one might have looked like, but I can tell you that not having access to them, there’s a great quote that I like a lot: “Art is born of constraint and dies of freedom.” So, the constraint of not being able to talk to the two main characters was enormous, but I think it gave rise to an art in the film that ended up being very powerful. Because frankly, revealing Bradley through his chats is both very personal and poignant and also reckons with that whole contradiction of the internet, a mechanism that is at once very intimate and depersonalizing, all at the same time. In the case of Julian, I think not getting Julian forced me to know more about Bradley Manning, and that ended up to be a very powerful thing also. And frankly, not getting the interview with Julian Assange probably caused me to raise more questions in a good way about WikiLeaks than I might have done otherwise. It taught me a lot not getting access to both of them.

Is it hard to make a film that speaks to both men’s admirers and their detractors without passing judgment?

Gibney: It is hard. There are probably ways in which the film goes past judgment in some way, shape or form or at least raises questions. I’ve been denounced now by Julian and also recently by Oliver Stone. Neither of them has seen the film, and that, to me, is very telling. I think if people come to this film with an open mind, they will find that the film is pretty fair and was intended to be that tent under which detractors and supporters could convene and talk about it. What a terrible world it would be if we only did films that were poster boards for political causes. That would be terrible and it wouldn’t teach us anything. It would just be kind of an echo chamber for ideas already held and wouldn’t unleash our great curiosity or our ability to understand more about the world. So I try to do that in some of my other films. In fact, I feel like I’m moving more and more in that direction. I remember when I did my Enron film, my executive producers at the time felt very strongly that I should mock the Enron executives more viciously because everybody wanted that moment. I felt just the opposite, that if you mock them, then they were ultimately irrelevant because then they were peculiar monsters that didn’t have any kind of connection to who we are, and I don’t feel that way at all.

What was your response to Oliver Stone?

Gibney: I tweeted my response to Oliver. So if you look on Twitter under my handle, you’ll find my response there. I basically said, “Maybe you should watch the movie before you attack.”

What are your thoughts about the role of media, transparency and the issue of privacy in the internet age when sensitive information can be accessed and disseminated with lightning speed without regard to motive or consequences?

Gibney: That’s what this film is all about. It’s all about the contradictions of the internet in terms of privacy, secrecy, transparency, and also truth and lies. Julian Assange is right to insist that WikiLeaks is a kind of truth machine because you have these documents. It’s also prone to being infected by lies as the organization itself was. The internet connects us all and provides this fabulous fact-checking mechanism, and yet at the same time, as we learned maybe more recently from the Boston experience, the power of lies is conveyed much more efficiently now because they’re accepted so fast. What was it, the phony AP wire story in the last few days that caused the stock market to tumble? So now we have to be wary. Everything moves so quickly that it’s very easy to form snap judgments that may in fact be wrong, and a lot of my career has been spent looking at recent news events, going back to them, and trying to disentangle fact from fiction.

What about when best intentions are undermined by human frailty?

Gibney: Well that’s what it’s all about. Again, I thought I was making a film about a leaking machine. It turns out to be a film about human beings and how human beings behave in unpredictable ways that sometimes belie your very best intentions.

How can new technology be used to speak truth to power and push for greater respect for human rights without compromising critical operations and political relationships?

Gibney: You see some of those contradictions in the film. I think Julian made a big mistake early on by not being more rigorous about redacting names. It could have caused people to be seriously harmed. At the end of the day, there’s no substitute for judgment. You can’t be mechanical about leaks. If I have a criticism to make of Bradley Manning, it’s that his leak was so massive. It was intended as a repository of great information which was in its own right valuable. But he put it in the hands of people who may not have been best suited to reckon with the possible damage that might have been done by those leaks. It’s never a perfect system. Of course, Julian might say, “Well I didn’t want to censor anything because then I’m in the same role as the New York Times which is too sensitive to political pressures about what to leak and what not to leak.” At the end of the day, I think the absence of judgment is also a kind of judgment.

In light of all of this, how do you view the future of journalism?

Gibney: I think the future of journalism is going to be a battle between caution and recklessness. And I think a little bit of recklessness is a good thing as some of the WikiLeaks cables proved. But in some fundamental way, the future of journalism is also about trust earned and how do we find sources that we trust, because the danger of leaks and leaking secrets is that lies can be leaked as well as truths. And how are we to tell the difference? In a busy world, even as information is moving so rapidly, we have to learn who to trust in that regard even as we ourselves have to become more critical of the people who we want to trust. It’s a weird situation.

Can you talk about your Lance Armstrong documentary, The Road Back, and how that’s coming along?

Gibney: It’ll probably be released this fall. Sony Pictures Classics has it. I’m still in the editing room with it, but I think we’ll probably lock picture sometime in late May and it’ll probably be available in the fall.

Do you have any other upcoming projects?

Gibney: There are a few things, but probably not worth talking about at the moment.