It’s always an interesting prospect when a director remakes their own film. Of course, remakes themselves are nothing unusual, but taking it upon yourself to retell a story you’ve already told is bound to elicit curiosity. The reason for such endeavors varies wildly, ranging from trying to unleash an idea’s true potential after it had previously been squandered (such as Michael Mann reconfiguring L.A. Takedown as his magnum opus, Heat) or as a means of reframing the themes of the original to make them even more profound (as Michael Haneke demonstrated with Funny Games, his 2007 shot-for-shot remake of his 1997 film of the same name). Either way, it’s an experiment that is never boring – especially when it’s being conducted by none other than the “Master of Suspense” himself, Alfred Hitchcock. Enter, The Man Who Knew Too Much, a pair of suspense thrillers released twenty-two years apart that marked the only time when the revered director would recycle a premise across his illustrious six decades in the business.

The Man Who Knew Too Much's story’s first iteration dates from 1934, a time when Hitchcock was still climbing his way through the ranks of the British film industry (and helping to define the entire thriller genre as he did). Jump forward to 1956 for his second attempt, and he was a changed man. Now he was a fresh-faced youngster no more, but a seasoned veteran who had earned the admiration of critics and audiences worldwide thanks to such classics as Rebecca, Shadow of a Doubt, and Rear Window (all made following his successful transition to Hollywood in 1939). The impact of those intervening decades is evident throughout his Americanized remake of The Man Who Knew Too Much. Both are solid examples of why Hitchcock is the undisputed king of thrillers, but together, they make for the most engaging double act of his career.

'The Man Who Knew Too Much' Is a Classic Hitchcockian Thriller

While both versions of The Man Who Knew Too Much feature sizeable differences, the outline remains the same: A happily married couple vacationing in a foreign country becomes embroiled in a global conspiracy after learning of an assassination plot against a European politician, and vow to take matters into their own hands after their child is kidnapped to ensure their compliance. It’s the classic Hitchcockian formula, combining the usual motifs of deception, mistaken identity, and the all-important MacGuffin (in this case, the dying words of a secret agent) to create a suspense-heavy melodrama for which the silver screen was invented. Hitchcock may have been a technical genius who made some of the most analyzed films in cinema history, but he also understood the most basic tenet of a film – that it be entertaining. As such, while the routine structure of The Man Who Knew Too Much ensured that it would never reach the intelligently stimulating highs of Vertigo or Psycho, its simple framework proved flawless when crafting a pulse-pounding story that would delight a mass audience.

With that being said, it’s worth noting that the 1956 remake is far from a carbon copy of its 1934 predecessor. Instead, the film repackaged the same broad synopsis into an entirely new script (the result of Hitchcock instructing his latest scribe, John Michael Hayes, to refrain from watching the previous film), giving it a unique atmosphere even while running through the same motions. For example, the husband-and-wife protagonists at the center of his murder-fueled tale have vast divergences. The original film focuses on a British couple, Bob and Jill Lawrence (Leslie Banks and Edna Best, respectively), holidaying in Switzerland with their daughter. They’re polite, reticent, and dignified even in the face of death… very stereotypically British, then, with Bob’s gentlemanly demeanor making the entire plot feel almost trivial in a way that compliments the film’s comedic undertones.

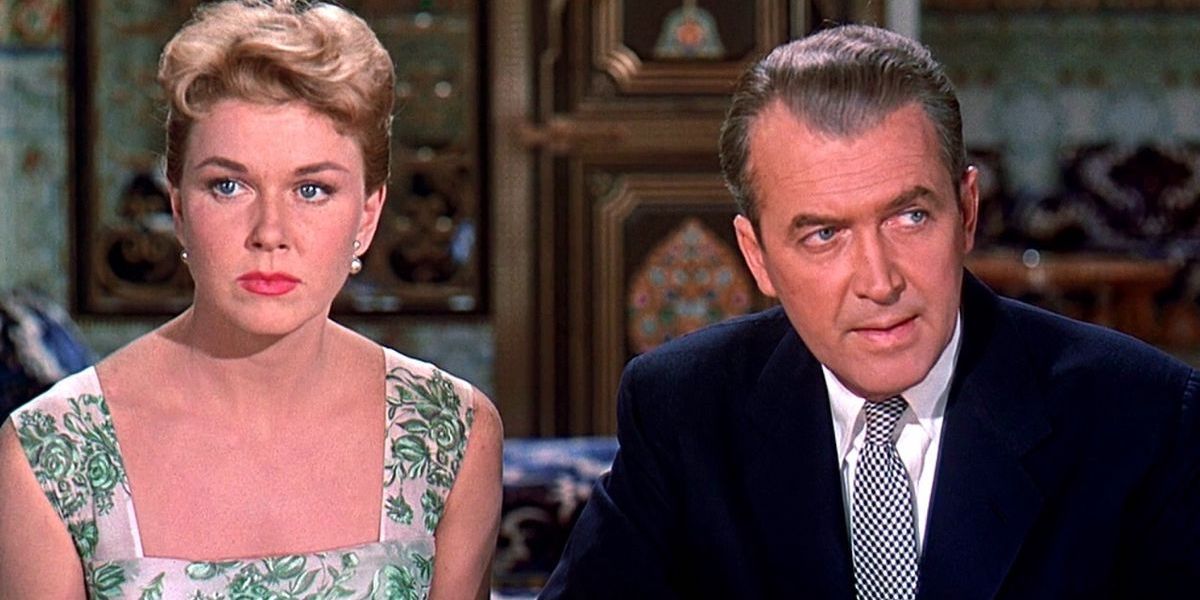

By comparison, the remake takes a more serious approach with its leads. This time around, our heroes are the American couple Ben and Jo McKenna (James Stewart and Doris Day, respectively) who are holidaying in Morocco with their son. Their characterization is more in line with a typical Hitchcock drama – that of an everyday protagonist thrust into an overwhelming situation they can barely comprehend (let alone hope to succeed in). Stewart was already an Alfred Hitchcock movie veteran by the time of The Man Who Knew Too Much, and while his performance falters compared to his work in Rope and Rear Window, his masterfully crafted image as cinema’s friendly next-door neighbor who refuses to let bullies win remains just as captivating as ever (while also heightening the story’s darker elements). His onscreen wife also has multiple improvements bestowed upon her. Best was a fine enough actor, but her character was so thinly written that she all but disappeared into the background for most of the original. Thankfully, the mesmerizing screen persona of Day gives the role a far more commanding and engaging presence, even if Jo does adhere to the usual Hitchcock Blonde archetype.

But these are only a fraction of the changes. With the remake gleefully casting aside everything about the original except its story (one can’t help but feel that Hitchcock was slightly resentful that original writers Charles Bennet and D. B. Wyndham-Lewis retained a credit on the new film, thus inviting comparisons galore), virtually everything that can’t be condensed into a one-page treatment is different. Pacing is the obvious example, with the original’s lean 75-minutes that sees Hitchcock operating at his most economic giving way to an exuberant two-hour runtime. Hitchcock puts this additional breathing room to tremendous use, allowing for a more finely constructed adventure that, in hindsight, makes the original feel utterly lightweight. The assassination attempt at the Royal Albert Hall – a standout sequence in both films – is rendered nigh on perfect in the remake thanks to Hitchcock’s willingness to linger in anticipation for more than a few minutes— a mindset that applies to the rest of the film too. The tenets of Alfred Hitchcock’s iconic style are also more visible, pushing the film closer to a reimaging than a boring old remake.

Alfred Hitchcock Considered the Original Film "The Work of a Talented Amateur"

The ultimate question hanging over The Man Who Knew Too Much is why Hitchcock made it twice. Many of his earlier films lacked the technical prowess of his later ones, and while he was hardly above recycling themes and plot points across his career, he never felt the need to outright remake a previous story other than here. According to the book Hitchcock/Truffaut (a transcript of conversations between himself and French New Wave director François Truffaut), Alfred Hitchcock had been contemplating a remake ever since relocating to the United States but only decided to pursue it in the mid-1950s to fulfill his contract to Paramount Pictures. To quote the man himself, “The first version is the work of a talented amateur and the second was made by a professional”. You might think that such a damning statement would sufficiently explain why the remake exists, but considering that most of his pre-The 39 Steps films could be described as “the work of a talented amateur”, the question of why this one was deemed important enough for a do-over persists.

Still, you won’t find many critics complaining. Hitchcock was a man of two nations – the unflinching reserved Britain, and the fearlessly patriotic America, with their similar but also disparate cultures putting his career into two distinctive eras. Theorists have long sought to juxtapose his Hollywood and non-Hollywood work, and owing to The Man Who Knew Too Much’s singular position as the product of both, it has proven itself as a remarkable asset in the field of Hitchcock Studies. The 1956 version – with its Technicolor visuals, booming Bernard Herrmann score, and pristine aesthetic – is an unmistakably American production, showcasing all of the tightly controlled mechanisms one associates with this dominant strain of filmmaking. In contrast, the 1934 film exhibits a strong British sensibility, putting greater emphasis on the farcical nature of its storyline that places it on the borderline of a comedy of manners. Tracing the lineage of a director’s style is always a fascinating journey, and Hitchcock was kind enough to gift his supporters with the ideal tool to complete this task (whether that was intentional or not) making The Man Who Knew Too Much an invaluable entry in his filmography.

Today, the overriding consensus is that the remake is the superior version. For the most part, this is true, but this doesn’t mean that the original is without merit. For one, even though the remake had all the money in the world thrown behind it ($1.2 million compared to £40,000), the limited resources of the original led to a more striking visual design (confirming the old saying about constraints creating creativity). Here, London is reshaped into a shadow-drenched alter ego that always seems out of step with reality – no doubt a lingering after-effect of Hitchcock’s expressionist-inspired work during the silent era. Similarly, while the villainous Mr. Abbott (an always watchable Peter Lorre) would appear ridiculous had he been depicted in full color, his cartoonish personality is perfectly suited for such surrealistic photography. Amazingly, Lorne spoke little English when he was hired (having only recently escaped Nazi Germany), forcing him to learn his lines phonetically. That he managed to overcome such unfavorable conditions to deliver one of the finest antagonist performances in a Hitchcock film is nothing short of astounding.

Viewing Both 'The Man Who Knew Too Much' Stories Together Makes for an Enlightening Double-Feature

To some extent, comparing both versions of The Man Who Knew Too Much is fruitless. Their stories may be similar, but the way Hitchcock goes about presenting them certainly isn’t, making dual discussions about them reductive to their individual visions. It’s possible that, given Hitchcock made the remake during the most artistically significant period of his career, the film was his grandiose way of ensuring no one would mistake the original for what it was – a first draft made by a gifted artist who was still a few years away from excellence. It’s a bold decision to try and dictate what should be viewed as the quote-on-quote “proper” film – especially since many prominent critics continue to champion the offbeat qualities of the original – but credit to Hitchcock for having the courage to do so. Regardless, his technical proficiency is evident in both, and watching them in conjunction transforms The Man Who Knew Too Much into an enthralling demonstration of how a student became the master. For those interested in filmmaking, they make for an essential watch.