To the strains of Blondie’s “Call Me,” an Armani-clad Richard Gere cruises along the Californian coast in an open-top Mercedes. Slick and perfectly styled, the opening scene of Paul Schrader’s 1980 film, American Gigolo, seems to welcome a decade of wealth and opportunity with open arms. However, Gere’s character is a high-end sex worker whose lifestyle unravels in a similar manner to so many of Schrader’s other protagonists. Soon to be re-imagined by Showtime, it’s reported that Schrader doesn’t like the idea of returning to the character or story. However the new show turns out, the original film is still potent – one of Schrader’s darkest in spite of its sun-drenched look.

In American Gigolo, Julian Kay (Gere) is a sex worker whose client list consists of older, wealthy women. He starts sleeping with Michelle Stratton (Lauren Hutton), the wife of a state senator and becomes implicated in the murder of a former client. As the police investigation closes in, and he’s abandoned by his rich friends, Julian becomes increasingly desperate in his attempts to find out who’s framing him.

Who Is Julian Kay?

“Why me?” Julian ultimately asks Leon James (Bill Duke), the procurer who sent him on the “rough trick” (sex with a sadomasochistic married couple in Palm Springs) that put him under suspicion of murder. “Because you’re frameable,” replies Leon, with no further explanation needed by that point. He had previously warned Julian that his rich clientele would eventually turn on him, as indeed they do.

At the beginning of American Gigolo, Julian’s lifestyle seems far from precarious. He lives in a superb apartment stocked with expensive art and a designer wardrobe. He frequents the bars and restaurants where his clients go, fitting in just fine. He gets jobs from a woman, Anne (Nina van Pallandt), in a reversal of the procurer/sex worker dynamic typically portrayed on screen. In her beach house, they argue about percentages and an important client who is flying in from Sweden (Julian is learning the language in preparation for the meeting). “You know anyone else who gets in the LA Country Club?” he snaps when Anne complains about his cut. There’s a sheen of respectability to proceedings, and most certainly the suggestion that in the rich circle Julian moves in he’s providing a well-accepted and very necessary service.

Look the Part

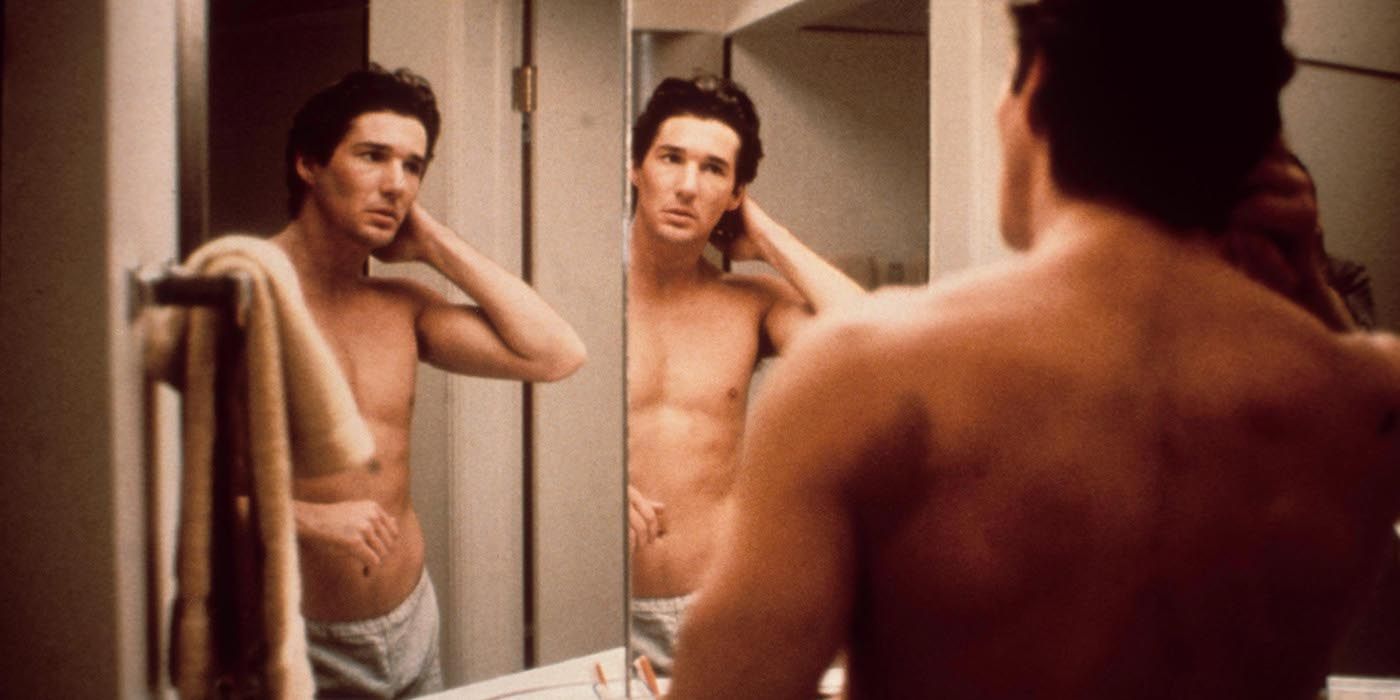

American Gigolo’s iconic moment comes when Julian, at the height of his powers, takes time to lay his many Armani jackets on the bed, matching them with various shirts and ties to a Smokey Robinson track. (The ‘80s loved a dress-up scene to music, notably Sleeping with the Enemy, but American Gigolo was the best.) There are references throughout the film to Julian’s carefully constructed image – the clothes, the car, the good taste – that allows him to fit into well-to-do society. Anne claims that she created him, in an effort to exert ownership. The look and feel of American Gigolo, from the pastel tones of Julian’s apartment to the Giorgio Moroder soundtrack, was incredibly influential in movies to come. On the surface, Julian exudes confidence and success, although there’s a nagging sense of unease common to many of Schrader’s protagonists.

How does Julian Compare to Other Schrader Protagonists?

Socially and geographically, Julian may be a thousand miles away from Travis Bickle (Robert de Niro), the protagonist of Schrader’s screenplay for Taxi Driver, yet similarities abound. They’re both men who throw themselves into their work. “It’s a long hustle, but it keeps me real busy,” Bickle proudly writes about the hours he puts into the taxi, suggesting work as an escape from darker thoughts. Equally dedicated to his job, Julian speaks of spending hours bringing an older client to orgasm. “Who else would have taken the time and cared enough to do it right?” he muses.

Schrader writes men who define themselves through the minutiae of their work. It’s a list that includes drug dealer John LeTour (Willem Dafoe) in Light Sleeper, pastor Ernst Toller (Ethan Hawke) in First Reformed, and gambler William Tell (Oscar Isaac) in The Card Counter. Like Julian and Bickle, they have their rituals and routines, along with a psychologically entrenched set of rules that ultimately makes them vulnerable. They most often end up in jail, talking to someone through a glass screen, or in a liminal state where the viewer is unsure whether they really exist anymore.

It’s not hard to see that the vigilante image Bickle constructs before his mirror (complete with hidden guns and a combat jacket) isn’t too far removed from Julian’s designer clothes. The squalor of Bickle’s New York apartment is a far cry from Julian’s pad in Westwood, but it’s equally a refuge from the world. “This is my apartment, women don’t come here,” Julian tells Michelle when she appears at his place uninvited. He’s offended after Michelle jokes she expected a red carpet and mirrors on the ceiling. Julian might be the most well-heeled of all Schrader’s protagonists, but his home is an escape and work is a way to both engage and shield himself from the world. His relationship with clients is about a job well-done rather than a real connection.

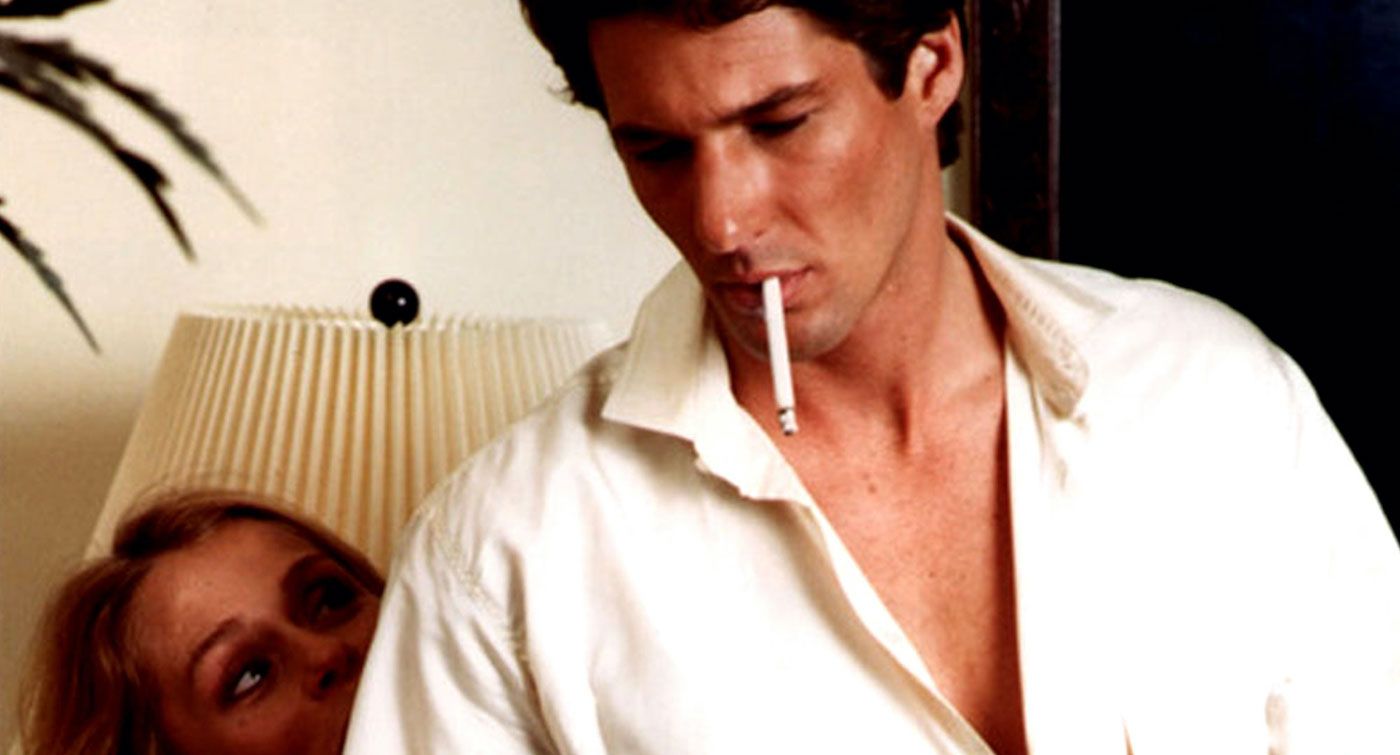

Sex Appeal

When Julian begins an affair with Michelle it’s business at first, but the film suggests it becomes a romantic relationship without ever making it clear when (or if) the transactional element ends. They’re certainly one of cinema’s most attractive couples. In the eventual sex scene – the only truly explicit one in the movie – they come together in an oddly static series of naked images (almost tableaux) that suggest cool detachment. It’s as if too much movement would detract from the formal perfection of the moment. The sex is as carefully curated as Julian’s image. A subsequent scene features full-frontal male nudity that was scandalous at the time.

Julian is portrayed as a narcissist, but Gere makes him relatable. As an actor, he’s never looked more beautiful on screen – whether floating through the high-class haunts of Los Angeles or just hanging out in his apartment. John Travolta was originally considered for the role, although Gere brings a more androgynous appeal to Julian. He’s a lust object that both women and men can appreciate. In the early stages, he’s a cipher, although as the plot to frame him for murder progresses his implacable cool begins to slip.

A Downward Spiral

Paranoid that someone has planted incriminating evidence, Julian tears up his apartment in the manner of Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation and then (most painfully of all) pulls apart his Mercedes. Another low comes when he goes to a restaurant looking unkempt and without a suit and tie, leading to rejection by Anne. By this point, we’ve started to see something of Julian’s buried past as he looks for answers among sex workers on the street and in gay clubs. In his most desperate moment, Julian offers to work exclusively for Leon, which would entail taking gay clients. This is a terrible fall, not because of the nature of the work (for Julian, sex is a job where there is no distinction between gay or heterosexual clients – although he dislikes the sadomasochistic ones), but because it compromises his prized freedom. “I can’t be possessed,” he told Leon in more comfortable times, referring to his unwillingness to work for anyone or any client for too long. However, facing a jail sentence, Julian is prepared to go back to where he started, which is clearly the streets.

What Lies Ahead for Julian Kay?

Talking to the Los Angeles Times in 1991, Schrader drew a connection between his protagonists in Taxi Driver, American Gigolo and Light Sleeper, stating they’re “not really a person but a soul in search of a body to inhabit.” There’s certainly a disconnection to Julian, the sense of someone looking for meaning in the manner of the ‘80s – through material possessions. These get stripped away from him throughout the film, to the point where he’s convicted of a crime he didn’t commit. His refusal to drag Michelle’s name through the press to save himself is a late show of moral fortitude that provides him something of a fairy-tale ending. However, Schrader’s framing of the final moments (cutting to black between successive scenes) seems deliberately stilted and out of joint with the rest of the film. Like many of the director’s endings, it makes one question what’s real and what’s wish fulfillment.

Schrader has said he won’t be watching Showtime’s American Gigolo, as an older version of Julian (Jon Bernthal) magically steps out of prison after 15 years and into the present day. Only time will tell whether Schrader is right to look away and consign his creation to a moment in history. As his 1991 interview suggests, Schrader’s been writing about this alienated character for many years and in many guises, so we haven’t seen the last of Julian – in whatever way he might manifest.