In the winter of 1974, a young man murdered his parents and siblings in their home. As of 2022, thirty-seven films, ten books and countless documentaries have been inspired by this crime. The circumstances of the massacre were bizarre to say the least, but when a young family bought the house cheap and moved in sometime later, a legacy of horror was born. The events of the winter of 1975-76 became known as The Amityville Horror, and almost 50 years later, the idea of a house haunted by the harrowing echoes of its past has never died.

To even the casual moviegoer, the title The Amityville Horror will probably ring a bell. It is regarded as one of the horror classics of the 1970s, albeit not one of the better ones, and younger viewers probably remember it cropping up on the remake conveyor belt of the 2000s. The several direct sequels to the original are more of a niche, cheaper spinoffs are lesser known still. The sheer scale of the Amityville series is staggering, and the extent to which each entry complies with or is even related to the ‘real’ story varies wildly.

Ronald DeFeo Jr. was a troubled, or troublesome, young man whose relationship with his starchy-collared parents was fractured at best. One night, he shot his entire family dead in their beds, within the walls of their dutch colonial Long Island house. How neither neighbors, nor seemingly the family members themselves, were stirred by the sound of rifle shots, is one of many enduringly mysterious components of the night’s events. DeFeo died in prison last year, having given decades’ worth of conflicting stories about his actions and motives, impressing that there was never any supernatural element to his crimes.

George and Kathy Lutz were newlywed when they bought the house in 1975 and moved in with their three children. Within a month, they had fled, claiming that increasingly aggressive paranormal activity had forced them from their home. Within a year, documentary writer Jay Anson had been tasked with penning a novelization of the Lutzes’ wild story; it became a controversial hit that underwent several covert revisions to accommodate the ever-changing narrative. The Lutzes were not exactly reserved when it came to making their story known: they hired paranormal investigators, they spoke to the press, they sued pretty much everybody who didn’t believe that it was ghosts - and not crippling debt - that prompted them to seek a way out of their unwise mortgage. Both went to their graves basically maintaining that the house on Ocean Avenue was haunted; their children have not expressed such certainty.

With the Lutzes and various investigators, including the infamous Ed and Lorraine Warren, having made the rounds of talk shows and news outlets, Anson’s novelization drew much curiosity, and soon a film adaptation was greenlit. Authorities in Amityville were less than thrilled that their sweet little town’s reputation was being further marred by association with the house on Ocean Avenue, so production took place in New Jersey and on LA studio lots, and a new wave of media attention began. The 1970s was marked by a 'Satanic Panic', which movies like The Exorcist and The Omen — and their infamous production processes - had only served to aggravate, so by the time The Amityville Horror came about, the press was all over it like… well, flies on a priest. In response to the media’s hunger for spooky anecdotes from the set of the latest demonic horror, the studio fed stories of strange goings-on, stirring public excitement that ended up delivering at the box office. Between the true crime, the controversial media circuit laps by the Lutzes, and rumors of another haunted movie set, it all felt so real, and the public ate it up.

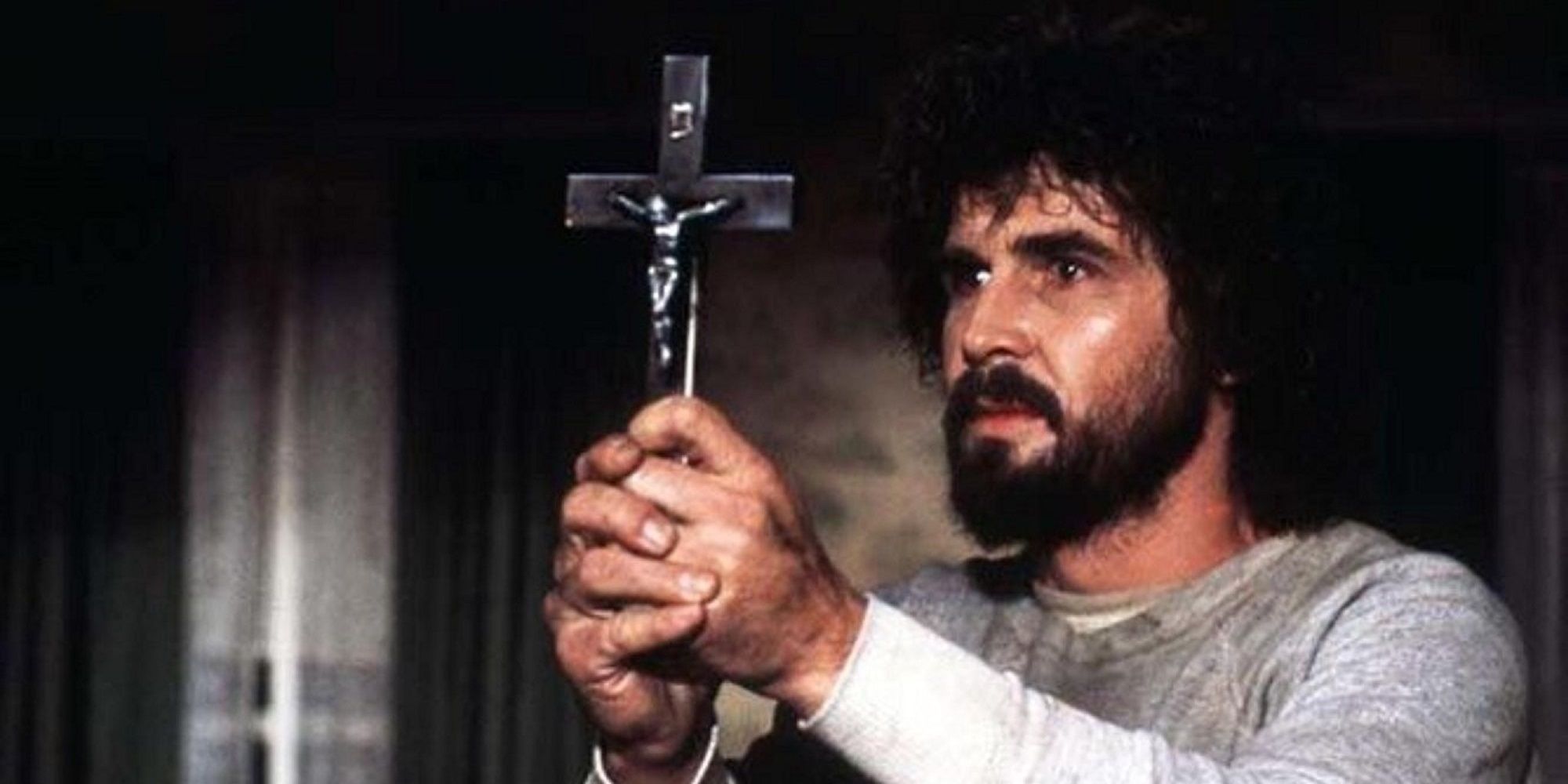

For such a classic, the original Amityville Horror is an overly long, tedious and at times amateurish affair. Margot Kidder and James Brolin doing his best psychotic-Barry Gibb-look play Kathy and George Lutz against a gloriously ‘70s backdrop of big glasses, brown florals and pigtails on 35-year-old women. They move into the murder house, knowing full well it’s a murder house, but conceding that “houses don’t have memories”. But all is not well. There seem to be malevolent forces afoot, and they go for low blows: first they make George unable to perform in the sack, then they magic away a relative’s money that he has to reimburse. Meanwhile, a number of spiritually-attuned acquaintances, from priests to hippies, get the proverbial bad feeling as soon as they set foot in the place. It becomes increasingly apparent that the house is a battlefield hosting the fashionable struggle between good and evil.

Where the movie really loses itself is in its desperation to be The Exorcist. The haunted house goodness is constantly interrupted by vignettes involving priests arguing over the legitimacy of actual demons in the 20th century. These insertions further bloat the runtime and often blatantly borrow from Friedkin’s classic. A glaring parallel is in the later involvement of an aged detective with a bushy moustache and thick glasses, who at one point sits down next to a basketball court (not a athletics track), wearing a tweed trilby and glances just off camera. The movie seems to think that the addition of a detective and priests bring a sense of sophistication to proceedings, where all it really delivers is inferior imitation and some truly amusing overacting. While the original has its moments - such as the sudden cut to silence as the demon howls for priest to ‘GET OUT’, or the early inclusion of a love scene to emphasise the later deterioration of the Lutzes’ relationship, in the tradition of Don’t Look Now - it is a slow, cheesy and remarkably unentertaining movie that looks artistically and intellectually inferior among its contemporaries of ‘70s horror.

If there’s one thing the remake can be given credit for, it’s being entertaining. It is slickly shot and edited, and blessedly succinct at just under 90 minutes, with much improved pacing and a real feeling of momentum. Despite being half an hour shorter than the original, it gets so much more done with its runtime and its characters. Kathy and George, played here by Melissa George and a seriously ripped Ryan Reynolds, seem like good people with a strong relationship, and we get to see much more interaction between them, which helps to sell the deterioration of George’s sanity. The three children are much more involved in the story too; they each struggle to cope with their grief and adjust to a new father figure, having lost their own father to some illness. George’s initial understanding and patience wanes as he struggles to find his own place in a pre-established family unit, and Kathy struggles to support and comfort her children while her marriage becomes increasingly strained. It almost crosses over into a domestic drama that examines how familial relationships become abusive, and even without all the ghosts, it is a relatable human story that is at times surprisingly poignant.

But while the remake does so well at crafting good characters and relatable narrative, it doesn’t forget that its job is really to entertain. While the original waffles on and never really seems to build to anything, the remake is like a guitar string being wound tighter and tighter until it is just bound to snap. Each day of the Lutzes’ life in the house builds upon the last, with tensions rising and trust breaking, until the inevitable murderous rampage brings the story to a thrilling climax that is fast-paced, frantic and tangible in its menace. It feels like a proper conclusion, and in keeping with the focus on the family’s relationships, it leaves many questions: how will all of this trauma impact George and Kathy’s marriage, or the children’s trust in their parents? Where do the Lutzes go from here? Although the ending - in classic mid-00s style - is marred by a silly tacked-on jump scare, it is a satisfying movie that holds audience attention, and seems to have pre-empted many stylistic choices that would later define haunted house movies, like The Conjuring, Insidious and Sinister.

In an almost beat-for-beat rehash of the original’s reception, the remake did very well at the box office, but was derided by critics; the studio and stars benefited, and horror audiences enjoyed it, even if they didn’t find it particularly fresh. Both major studio Amityville movies did what was required of them: made good money by serving all the staple dishes of the horror cuisine. But from there, the series is one long downward slope, both in terms of quality and performance. Amityville 2: The Possession, considered by some to be a cult sleeper hit, received a theatrical release, as did Amityville 3-D just a year later in 1983. However, the box office appeal seemed to have slipped, perhaps due to the increasingly slasher-oriented horror that was popular at the time. The series was unceremoniously demoted to made-for-TV and later straight-to-video status, and even when the remake did well, big studios seemed fairly over the whole idea. But that’s not to say that there was no audience interest, or that the franchise had run out of steam.

Ever since the Lutz family occupied 112 Ocean Avenue in 1975, interest in their story, and that of the DeFeos, has never died down. It has endured a number of horror trends, from the satanic panic of the ‘70s, the ‘80s slashers, the millennium’s renewed interest in haunted houses, and always seems to have something to offer to the genre. Its homegrown folklorish character certainly seems to have something to do with its undying popularity, helping to bridge the gap between fiction and reality. The 2005 remake even uses ‘Based On The True Story’ as its tagline and opening title card, making the horror feel more accessible, closer to home. This semi-true element proved to be crucial to other filmmakers not only taking the story and running with it, but being legally allowed to do so. American law dictates that as real historic figures, the stories of the DeFeos and Lutzes cannot be considered intellectual property, although fictionalizations such as Jay Anson’s book can. To this effect, Anson’s widow sued Miramax over the appallingly-received Amityville: The Awakening in 2017, which is just the latest in a long history of lawsuits associated with the movies.

While the Amityville series has never gained critical acclaim or cultural prestige, it has done perhaps the most desirable thing of all: made an impact. Paranormal activity aside, it is a story about people, about generational trauma, the cycle of abuse, the intricacies of family breakdown, and this clearly strikes a chord. After all, the scariest kinds of horror movies are usually the ones that are about the struggles of being human, and not feeling safe in one’s own home or around one’s own family is so basal a fear that it is practically instinctive.