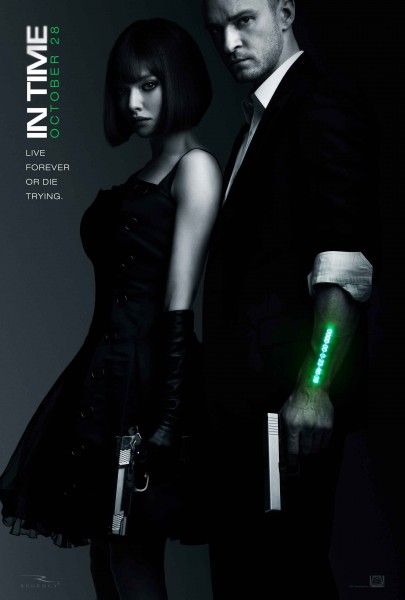

In Time wears its satire on its sleeve. I don’t think I’m being particularly observant when I say that the whole “those-with-time vs. those-without-time” serves as a parallel to the growing wealth divide in the country. It’s pretty implicitly stated within the runtime. That a film about youth (surrogates: Justin Timberlake and Amanda Seyfried) revolting against the wealthy upper class is coming out in the wake of the Occupy Wall Street movement(s) feels particularly timely or, if you’re cynical, opportune. It’s hard to look past that this film admonishing multi-billion dollar corporations is at the same time funded by the very beast it calls afoul.

In the following exclusive interview with writer/director Andrew Niccol (Gattaca), he speaks about the parallels between In Time and current events, discloses how he convinced a multi-billion dollar studio to fund a film highly critical of multi-billion dollar corporations and plays coy (sort of) on the fairly radical ideas the film advocates. Niccol’s also briefly touched on adapting the upcoming Stephenie Meyer’s novel The Host for the big-screen. For all this and more, hit the jump.

In Time does feel particularly prescient now given the Occupy Wall Street movement. What is your stance on these current events?

ANDREW NICCOL: Even making the movie in Los Angeles was pretty stunning because we would be shooting one night downtown on skid road and the next night we would be shooting in a mansion in Bel Air that was the size of Versailles. So the disparity between rich and poor was just impossible to ignore. Because we are always showing poor zones and rich zones, I was shooting in those locations. Places where you can get a room for literally five dollars a night and then you go to these massive mansions…

Was using those real locations an effort to make this world more tangible and to draw the social satire out?

NICCOL: Yeah. I obviously needed some way demonstrate that. I think someone at one point in the movie says ‘how can there be men with a million years when most live day to day’ - so we had to draw those contrasts.

The movie posits the solution [to the dystopian “time divide”] is a redistribution of time, which of course correlates to a redistribution of wealth. Do you feel that’s the solution to the current economic woes of the country?

NICCOL: I make movies. I’m not in politics. But I think there’s probably enough to go around, if you know what I mean.

Well then - how do you convince a multi billion-dollar studio to fund a film that is ostensibly admonishing multi billion dollar conglomerates?

NICCOL: You’re not going to tell them that are you? I’m not going to… Listen if you go in with a pitch and you say no character’s over twenty five years of age and there’s a ticking clock in every scene, they just go ‘where do I sign?’ They don’t read the script. Fortunately.

When you write, do you deliberately come up with these high concepts to appeal to studios – so that you can sneak in your own sensibilities?

NICCOL: I don’t do it deliberately. I’m always just trying to tell a story that I would want to see. I’m doing it for myself really but sometimes you’re fortunate enough that it’s what they consider high concept enough to finance. Often times it’s not – those are the films of mine you haven’t seen.

“Haves vs. Have-nots” is a common theme in your films. In this film, it’s those with time vs. those without. In Gattaca, it’s eugenics – Pure vs. impure genes. What is it from your personal experiences that influence this thematic undercurrent?

NICCOL: For me – I don’t think it is the “haves vs. have-nots”. It’s becoming more the will-haves vs. the will-not-haves. If you’re born into certain circumstances, you don’t have much of a hope frankly. The game is rigged and that’s why it’s always interesting for me that people vote against their interests. I point out in this movie - Vincent Kartheiser’s character says ‘everybody thinks they have a shot at immortality.’ Everyone thinks for some reason they have a shot at winning the lottery but they don’t. I’m here to tell them they don’t… Also I’m always, I guess rooting for the underdog.

Well then – how does the underdog achieve the impossible and succeed in ‘this rigged game’?

Pause

NICCOL: How do you do it? If you look around the world – how they’re doing it is through revolution.

It seems that’s what the film is advocating for: fairly radical revolution.

NICCOL: I wouldn’t argue with that.

You’ve spoken about how the film is about the “obsession with youth”…

NICCOL: Yeah… I mean if we could switch off the aging gene we would. There’s no technology that we’ve had that we haven’t used. We are in the capital of staying young forever. We never actually say that we’re in LA but we don’t say we’re not in LA either. People go to such extremes to stay young now that you know that they would do this in a heartbeat.

The movie posits that being young forever would make you weak, would make you content and not want to do or accomplish anything else – which again correlates to extreme amounts of wealth – but you’re a successful, affluent filmmaker who continues to strive…

NICCOL: Well I’m not as successful as you think. No, the most interesting thing in the movie might be the death of urgency. That if you had so much time – why write the next great American novel today when I can do it in the next hundred years. For me that was interesting. My favorite character in the movie is Matt Bomer’s character Henry Hamilton who’s immortal and wants to die. I think our psychology may not be able to keep up with our biology.

What made you then focus on Justin Timberlake’s character versus Matt Bomer’s?

NICCOL: Matt Bomer is sort of like one of those Dickensian characters. Even though he’s out of the movie fairly quickly, the whole movie is referring back to him really. So he’s kind of in the movie the whole time but just not there on screen. I guess I just like the underdog. I don’t want to focus on a guy --- It would be like focusing on the guy from Bel Air, instead of the guy in Compton. I mean you have a million years and you want to die. Please…

You often use science fiction as the means to pass your social commentary. What is it about the science fiction genre that appeals to you?

NICCOL: I think it was Sam Goldwyn who said ‘if you want to send a message, call western union.” So my first obligation is to entertain but as far as science fiction goes, it’s much easier to comment on today from another time because people then aren’t focused on ‘did you get the details right?’ It’s sort of a Trojan horse approach to ideas because it’s wrapped in the future, it’s wrapped in action, thriller and Oh look - suddenly an idea popped out.

The next thing you’re working on is The Host, which you’re adapting. What is the process when you’re working with original material vs. adapting a pre-existing novel?

NICCOL: This is the first time I’m going to be directing someone else’s story and it’s quite liberating actually because I don’t have to make it up. It’s there. It’s very freeing. If you write and direct it, it’s all your fault. There’s no one you can blame.