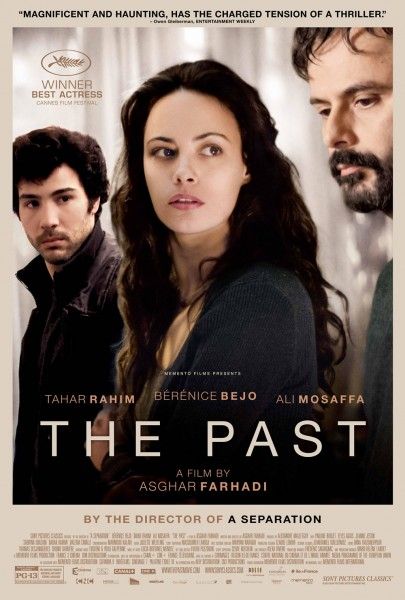

The Past, Iranian filmmaker Asghar Farhadi’s follow-up to his Oscar-winning A Separation, is an intricately crafted human drama that examines the complicated emotional and psychological bonds of a family in turmoil. Following a four-year separation, Ahmad (Ali Mosaffa) returns to Paris from Tehran to finalize his divorce from his estranged wife Marie (Berenice Bejo) who wants to marry another man (Samir/Tahar Rahim). During his brief stay, Ahmad uncovers the dark secret that explains Marie’s conflicted relationship with her rebellious teenage daughter Lucie (Pauline Burlet). Opening December 20th, The Past is Iran’s official submission for this year’s Best Foreign Language Oscar.

At the film’s recent press day, Farhadi talked about how a friend’s recollection inspired the story, why he likes to write flawed characters but tries not to judge them, his casting philosophy, how he chose to contrast the two male characters and worked with the children to create very natural performances, his decision to shoot in the Parisian suburbs and distance himself from the more familiar romantic settings, why he used very little music in the film, the powerful but hopeful ending, the challenge of making a movie in a language other than his own, and his thoughts on the controversy surrounding the film’s Oscar bid. Hit the jump to read the full interview.

Question: How did this project come together and what inspired your story?

ASGHAR FARHADI: This story, in fact, came after me years before because it was a recollection that a friend of mine had recounted to me of a memory he had. Before making my third film, Fireworks Wednesday, I was trying to make an appointment to see a friend of mine, and he said, “Oh, you know, I’m not going to be around because I’m going out of the country to see my ex-wife.” He told me they had been separated but they hadn’t formalized the divorce. This memory remained with me in the sense that I kept thinking what an odd situation to travel to another country to visit an ex-wife and to stay with them. This creates a kind of dramatic situation, although at that time, it did not occur to me that it could be made into a film or that I would make it into a film. It was much later that I thought, “I can make a film out of this.” Nothing awful or terrible happened to my friend. He went and they peacefully formalized their divorce, but in the story, things happened differently.

One of the things I love about the film is how there are no good or bad characters in the traditional sense and that everyone is very flawed and human. Could you talk about that? And also, does it bother you when others judge the characters?

FARHADI: During all of my writing career, this includes when I was writing plays and my other screenplays, I don’t recall ever writing a negative character, which does not mean that my characters aren’t flawed or do not make mistakes. In actual fact, they all are quite flawed. But why is it that I say they are not negative or not bad? That’s because in the film we see the reasons for their errors and we feel that were we in their position we might likely have made the same mistakes. Their negative actions or their mistakes don’t stem from a negative nature. It’s the conditions of their environment that force them onto a path that perhaps they themselves don’t even want to walk. This phrase, “everyone has their reasons,” is one that I subscribe to for all of those characters. The other point I want to raise, and it’s quite important to me, is based on what standard or on what pattern or view can we call one conduct good and another one bad? I don’t have a problem if someone else were to say that one of my characters is a good one and another one is not and is a bad one. I try myself not to have any judgment towards my characters, but certainly the audience might. Based on their own personal experiences and their own temperament, each viewer is bound to give one character greater rights and another one lesser rights. In a sense, this allows the viewer through the film to come to know themselves better.

Did the script change at all during production?

FARHADI: The pace at which everything is fluttering, developing and changing is so rapid and over a period of time is such that I don’t honestly know whether it resembles or doesn’t resemble [what I originally envisioned]. It’s like a person who, as they grow older, their face changes, but they don’t necessarily notice that themselves. However, prior to starting to shoot, the screenplay was complete and there were no changes that occurred during the production. There were some changes in the details, but in the fundamentals and structure of the story, there were no changes.

How did the casting of your three leads come about? Was it as fated as the story?

FARHADI: I believe, at least in cinema, that all of this stuff has been decided in advance and that all we’re doing is going forward and pulling aside the curtain and discovering. Whenever I write a part, I think there’s this person somewhere in the world that this part is specifically for and all I have to do is go searching to find that particular individual. When I wrote the part of Fouad, friends of mine said, “It’s very unlikely since you don’t speak French that you’ll find the child that could play this part the way you’ve written it. It might come out not so great.” But one day the door opened and he entered as if somebody had sent him.

When casting your film, did you try to match their look or their acting skills?

FARHADI: It’s all of it together. But there are also some subsidiary, tangential things that one has to watch out for when casting. These details spring from story. For instance, there’s this phrase that Lucie utters. She tells Ahmad, “My mother went for Samir because he looked like you.” I was compelled to choose two people that after hearing that sentence – not before – you might think maybe Lucie’s right, but not so resembling one another that one could decidedly say Lucie is right – it had to be so-so. I tried to find two actors whose features and gaze were close to one another. I didn’t have a full free hand in this area, but within my means, I did what I could, and then even later after the casting, I tried in makeup to somehow accentuate it.

There’s a stunning two-shot of the two men at the kitchen table that’s very long and quiet and incredibly moving. Is this something you envisioned beforehand or is it something you discovered in the shooting and in the editing?

FARHADI: The scene existed in that way in the screenplay. Continuing the remark I just made, I needed to one time set both characters in the frame together so that the viewers would compare the two of them. It’s long precisely so that this opportunity can be afforded to the audience to compare the two of them. We even tried our best to match the color of the clothes of those two actors so that audiences would focus on the faces. This is where the viewer can ask themselves, “Which of these is the man of the house?” The audience has an opportunity to think, “Do these two really look like each other? And because Samir resembles Ahmad, is that why Marie has gone and chosen Samir?” The fact is that both of these men, in my opinion, express a kind of outsiderness towards that house.

There’s a scene in the kitchen where Ahmad is preparing a traditional meal that suggests a sense of heritage within the family. Was that intended to also demonstrate that he’s providing for them?

FARHADI: This scene has several functions. One is, there’s perhaps some competitiveness between the two men – each one trying to show himself to be more the man of the house. For instance, Ahmad does the shopping, does the cooking, fixes the bicycle, deals with the children, so much so that one starts to think maybe he is more the man of the house. When Samir comes the next day, he’s like, “No. I’ll fix the flush on the toilet,” and he starts to paint and is trying to position himself in that part. But another function of this scene is Ahmad’s characterization that seems to be somebody who’s more attached to the past, who’s looking behind. The kind of food he’s preparing is a very traditional meal.

Is it the actor’s choice as the character to play lots of moments with no words or is this coming from the director’s point of view?

FARHADI: I think it’s both. It’s impossible to separate these two things. Because a character like Ahmad, and in fact, all the characters in the film, are such quiet types within whom there is so much tumult that there necessarily has to be these quiet moments. There’s more silence in this film than in any of my previous films. It might be because the situations in which the characters find themselves are inexplicable to themselves and also to others. They’re not able to explain why it is that they have done the things they’ve done.

How did you work with the kids to bring out those very natural performances and help them go to some pretty emotional places?

FARHADI: Working with children is very different than the way in which I work with adults. One has to work just as much with children as with adults, but the manner of work is very different. I never tell the children the actual truth of the thing that I want them to act. Although children are really into play and play acting, and this is a major part of their existence, they never actually find the playing or acting of adults credible. One must never tell a child what it is they should display acting. For instance, your mother is now in a coma and you should act unhappy because of it. Just as with the adults, I rehearsed for several months, a few days a week, with the children. Most of the time was spent during those rehearsals in making the inner relationships between the adults in the story credible to the children.

How would you describe the role of the house in this film?

FARHADI: Seeing as my films are frequently about family, the house ends up playing a major role in it. The house gets transformed into something like a character. It’s as though there’s a reflection of the interior of all the people that can be seen on the walls of the house. For instance, in A Separation, the home that we see is a composite of a traditional home and a more modern one. In the kitchen, some of the stuff is older. There’s an older fridge and on the other side there’s a much newer one. In The Past, the architecture of that house is very unique and has a lot of turns and hidden spaces and broken spaces. So, after one’s seen it, one can’t really say what the shape of it was – a little bit like people. The space of this film, the walls of it, the way they are painting the walls of it, it seems to me to be a reflection of the inside of the characters.

From a western standpoint, we’re not used to seeing Paris shown in a non-romanticized way. Was that conscious or is that your particular vision of Paris?

FARHADI: The image we have of Paris, if one is not Parisian, is the image we’ve been given by the cinema, and that’s a very beautiful, somewhat romantic vision with its very beautiful and likeable architecture. But in my story, I’m assuming the source of its inspiration is not cinema but life. In Paris, if you take an RER suburban train, buy a ticket and ride ten minutes outside of the city, you’re somewhere that in no way resembles that Paris that you’ve been told. I made the decision to distance myself from that Paris of cinema, even though it might have been a lot simpler had I decided to stick to that image of Paris. I chose the main character’s home in the suburbs of Paris. Being there, the woman who’s now been left by Ahmad seemed more solitary, more abandoned and this appealed to me.

I loved the film but why was there no music which is something we only see in a very few films?

FARHADI: Ever since my third film onward, I tried to use very little music, not because I don’t like music. Actually I like music a lot and I listen to a lot of Persian music. But stemming from the fact that these films are attempting to be real and to represent the real, I can’t subscribe to music, to the idea of where is this music suddenly appearing from? In most films in conventional cinema, when they use music, they in a way want to accentuate our emotions and this isn’t something that I require. I think that my audience is sufficiently engaged emotionally with the film. The fact that I do place music at the end of my film is not to accentuate the emotion. It serves an opposite purpose which is to remove them from the emotional space of the film and allow them to enter a space of thinking, because I believe that when the audience is watching the film they’re watching it with their feelings. What I wish for is that when the film has ended, those feelings can be transformed into thinking. And this ending, the last scene of the film, and the title with the music over it, I think does perform that action.

The ending is so powerful and also so hopeful and redemptive. Was that something you always thought of when you were telling the story because you wanted it to end on a hopeful note?

FARHADI: It seemed to me that the film’s ending was just as complicated as the story. It’s not a grim and pessimistic ending, but it is a melancholy one. This is the first time that at the end of my film I’m also playing in a way with the audience. This is not something that I’d done in my previous films. At the end of the film, the man has put on the perfume and is awaiting a reaction from his wife. There is a teardrop that begins to fall in response to this perfume, or perhaps not in response. It might be an uncontrolled event that the audience does see but that the character does not see. But next, we go to see their hands and we’re waiting for the woman’s hand to move, whereas in fact, we’ve just seen the tear. It’s as though we have been placed in a situation where we’ve forgotten that. Why is it that we are not able to have faith in the teardrop and are awaiting another miracle? This is something that the characters also have throughout the story. They’ve seen things that they’ve forgotten or they refuse to believe.

When you won your Oscar for A Separation you said that you hoped that people would see the beautiful people of Iran. How do you think things have changed in the past two years? How have you been welcomed back home?

FARHADI: What I would do is to separate the situation of the people of Iran from the situation of the government or state. What I said when I spoke was about the people. As I said there, the people of Iran, and not just the people today but throughout history, those people’s temperament has never been a belligerent temperament. When there is any disrespect towards them, they get very upset. And when they’re respectfully treated, they’re very happy. After what happened for A Separation, when I returned to Iran, they were very happy and I received a huge degree of affection from the people. Not so much perhaps from the government.

Can you talk about the challenges of making a movie in a language other than your own? Also, was there any controversy that Iran’s submission to the Oscars was mostly in French?

FARHADI: Well, in any event, if you are making a film in another language than your own, you are doing something out of the ordinary. This is not something I would wish to repeat always, but sometimes there’s a story that comes and seeks you out and will not leave you alone night and day and you feel compelled to make that film. If you have to do that, then you have no options. You have no other choice. I liked this story so much that I did decide to take that risk on. My attempt was not to see this as a problem, but to see it as a unique characteristic and to use it as such. Today, it gives me great pleasure knowing that when native French speakers see this film, everything appears credible to them and they don’t feel that this film was made by someone who doesn’t speak French. Regarding the fact that the film was presented for the Oscars, I’m very pleased about that. I’m very pleased that the film was presented from my own country. This selection did have its opponents in Iran who felt that because the producers and the money that had backed the film were French, this film was French. But I feel that putting aside the fact that the cinematographer, sound person, director, writer, main character, secondary character are Iranian, there’s also an Iranian gaze and this is what specifies the film’s identity as Iranian.