Throughout Blue Bayou, the Crescent City Connection (CCC) bridge can be seen stretched across the background of a southern sunset. The film — directed by and starring Justin Chon — takes place in New Orleans, where protagonist Antonio LeBlanc (Chon) has made a home and family life with his wife Kathy (Alicia Vikander) and stepdaughter Jessie (Sydney Kowalske). Antonio is a Korean adoptee whose first foster family failed to file the necessary documentation that would have granted him American citizenship. When he is apprehended by the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) decades later, life as he knows it is threatened by his imminent deportation. The CCC bridge not only establishes the importance of setting — as much of the film takes place in the suburbs where, as Chon tells Kodak, “more of the everyday Westbank people across the [Mississippi] river” live rather than in the flashy, tourist hotspots of New Orleans — but the bridge is also a symbol of the Asian-American experience. Antonio has spent nearly all his life in Louisiana, going from one abusive foster family to another. He has vague memories of his mother from Korea, but his commitment to his wife and stepdaughter — and a baby on the way — demonstrate his attachment to the U.S. And yet, despite Antonio’s surname of LeBlanc, and despite being an “Asian man with a Baton Rouge accent” as Chon describes his character to GQ, he is still ostracized and viewed as a foreigner. Like the bridge, Antonio is caught between two ends.

I’ve been to New Orleans a number of times since I’ve moved to Louisiana for graduate school in Lafayette. And I’ve driven over the CCC bridge to get to the city, as well as seen its prominence overlooking the outer suburbs. When I had first moved to the Deep South as a Filipino immigrant who grew up in the Northeast, I had my own misgivings about becoming an Asian-American “Yankee” transplant in Cajun Country. Would there be others like me? Would I feel at home? What I didn’t know before moving to Louisiana was that Filipinos have had a history in the state. Filipinos, who arrived in Louisiana from the Philippines in the 18th century, escaped their Spanish captors and settled in the bayous. They even had a settlement known as “Manila Village.” So I wasn’t the first Filipino in Louisiana, despite my apprehensions and feelings of solitary movement. Still, my desire to connect with other Filipinos — which was easier where I had grown up in the Northeast with its large pockets of Filipino communities across the New Jersey-New York area — led me to a Filipino restaurant in New Orleans. I took a two-hour bus ride from Lafayette to get to the city, then rode a ferry across the Mississippi River. I walked through the suburban neighborhood to get to the restaurant. In the background, I could see the CCC bridge — the same bridge that Antonio LeBlanc and his family see in Blue Bayou.

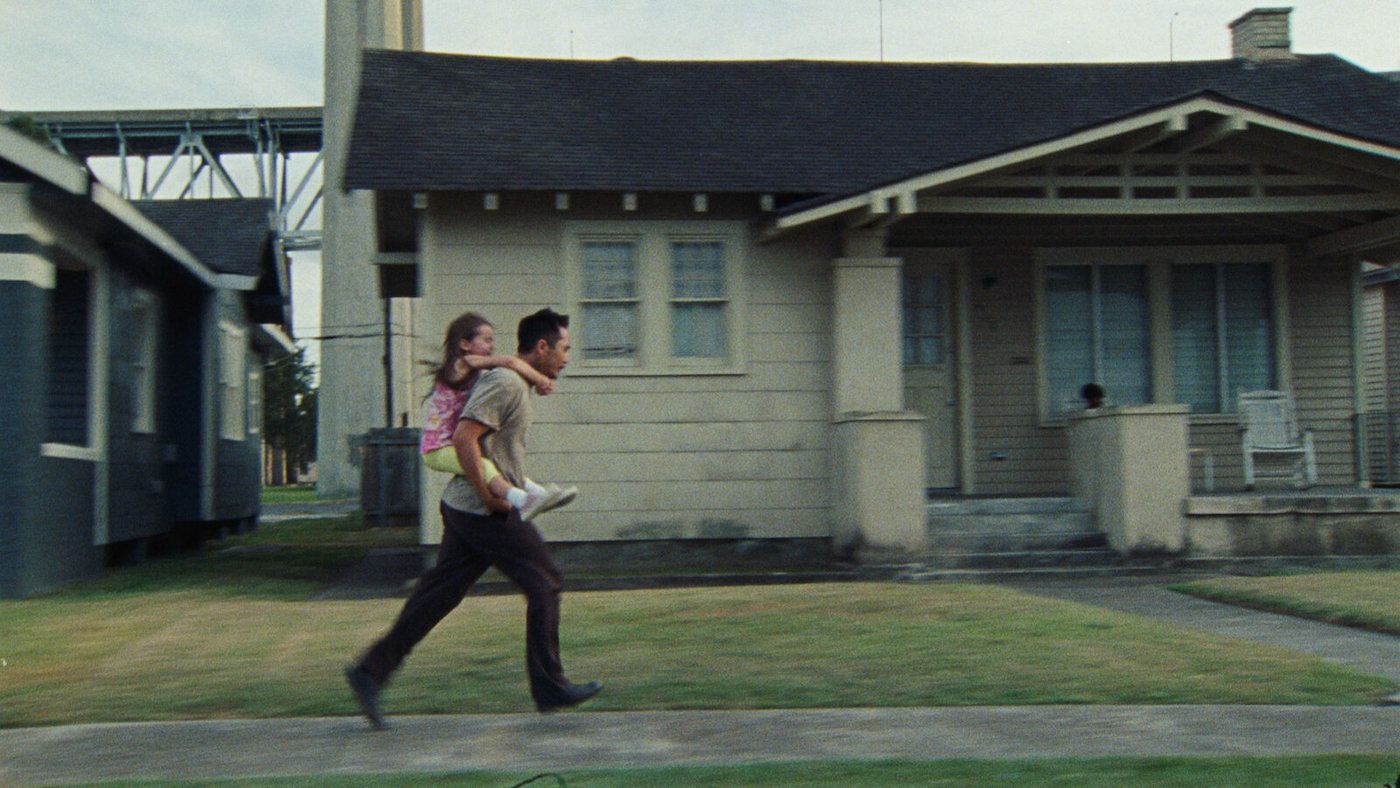

Just as I haphazardly planned a trip to NOLA solely to eat Filipino food, which was well worth the trip and fulfilled my crispy-pork cravings, I recently made a similar impulsive decision to drive over to the nearest theater that was playing Blue Bayou. From its opening scene, I was hooked — and by hooked, I mean that I was immediately teary-eyed and captivated by Justin Chon’s directing and storytelling. My raw emotional reaction from the very first frame was part of the effect that Chon had in mind. “I definitely wanted to shoot on film and 16mm," Chon told Kodak. "Blue Bayou is a story about an American family in the South. I felt it was necessary that this feel immediate and tangible...16mm gives it another level of emotionality.” During the opening scene, the camera is steady, framing Antonio LeBlanc’s and his stepdaughter’s faces up-close. Off-screen, an interviewer asks Leblanc some questions concerning his employment history and work application. Inevitably, Antonio is asked the question “Where are you from?”, a question that many people of color know all too well. It’s a nuanced question — not only does it show others’ perception of Antonio as a foreigner, but it’s also a question that Antonio must answer for himself as the movie progresses. Where are you from? Where do you belong? He was born in Korea to a mother who sent him away. He was adopted by a white American family who abused him as a child. And now, just as he’s felt the most at home with his pregnant wife and stepdaughter in New Orleans, he faces deportation back to Korea. There are certainly complicated layers to Antonio’s story.

Chon further complicates his portrayal of the Asian-American experience by incorporating another character whose story is juxtaposed with Antonio’s. Parker (Linh Dan Pham) came to Louisiana with her father as refugees during the Vietnam War. Antonio meets her at a hospital, where he’s there for his pregnant wife while she’s there as a cancer patient. Parker and Antonio may come from different countries, yet from the (white) outsider perspective, they are perceived as more common than different. “You look like my dad,” Jessie draws the comparison between Parker and Antonio. It’s an innocent comment from Antonio's stepdaughter, yet their commonalities are further observed by Parker’s father, pointing out the similarities between Vietnam’s and Korea’s history of war and their strength and resilience afterward. “I think a lot of times in film, it just feels like it has to be a Korean American film, or British Chinese, or Vietnamese American,” Chon continues to tell GQ. “But wait, we all hang out, why does it have to be separate.” Chon walks this fine line as a filmmaker, but he manages to point out the universality of the Asian-American experience without erasing the specific histories and contexts of individuals.

Even as many of the film’s themes relate to the larger Asian-American experience and other immigrant experiences, Justin Chon avoids pigeonholing his characters in any one category, and that sense of unlocatable misplacement is part of the dramatic, emotional appeal of Blue Bayou. I definitely felt misplaced when I first arrived in Louisiana — having come to the U.S. as a child with my family from the Philippines and then having moved to the South as a Northeasterner. I had found a small grocery store near my apartment. It was a mom-and-pop that not only sold miscellaneous produce and frozen foods, liquor, and household pantry items, but they also prepared Asian dishes like fried rice, noodles, and garlic shrimp. My first time there, the man at the counter spoke to me in a language I did not understand: Vietnamese. I explained that I was Filipino, not Vietnamese, and apologized before I left. Still, I understood his intentions. I too am always on the lookout for others like me.

I return to the image of the CCC bridge over NOLA. A bridge is caught between two ends, suspended in the middle of two places. But a bridge also connects, despite the difference of starting and end points. What I’ve found in Louisiana, and what I’ve also found in Chon’s film, is that these connections are everywhere. In Blue Bayou, Antonio makes an unexpected connection with a Vietnamese woman dying of cancer. But his white American wife and especially his stepdaughter, who calls him “Dad” rather than her estranged, biological father (Mark O’Brien), accepts Antonio as their own. I’ve similarly come to find a community with my peers as a graduate student and have met some locals in the cafes I frequent. They’ve helped me, especially during hurricane season, which I am not used to at all, to gather supplies and prepare me for what is to come. In Lafayette, the center of Acadiana and Cajun culture, I’ve found parallels between my Filipino culture and theirs. Take, for instance, the visual similarities between the Filipino flag and the Acadiana flag, or even our common culinary investment in pork. The Cajuns too had come from elsewhere to Louisiana, as the original French Canadians were expelled by the British. It’s an interesting choice, then, for Chon to set the story of a Korean American threatened by deportation in Louisiana, a true melting pot. There are complexities to Blue Bayou that aren’t often found in many films. From the tragedy of separation to the beauty of connection, Blue Bayou spoke to me in unexpected, poignant, and mesmerizing ways.

The film premiered at the Cannes Film Festival on July 13 and was released in U.S. theaters on September 17.