Since its first appearance as an anime adaptation in 2013, Hajime Isayama’s action/horror, Attack on Titan, has taken the world by storm, even interesting viewers who don’t typically watch anime. It has been referred to as the anime world’s Game of Thrones – complete with crazy plot twists, subversions, and mysteries aplenty. But one of the most impressive elements of Attack on Titan is its ability to create, introduce, and develop the scariest part of its universe: the monsters.

Monsters have been deeply ingrained in storytelling, from ancient Greek myths (the Minotaur, Medusa) to modern-day horror films (Pennywise, death angels). In many ways, the monster has been a figure against which heroes rally and win, against all odds. And even though Attack on Titan also has a large focus on action scenes and mystery elements, the story is centered around its own form of monster: Titans, giant cannibals that exist for no other reason than to eat humans, bringing humanity to the brink of extinction.

The original Japanese word for these monsters is kyojin, spelled with two kanji characters that roughly translate to “big” and “human,” together meaning “giant.” The word used for its introduction to the English language, “Titan,” is perhaps the best translation for Western audiences, considering its origin in mythology: Cronus, the last living Titan (a creature of immense power that predates even the Greek gods), is most well-known for cannibalizing his own children.

In this apocalyptic world, the dwindling number of humans know next to nothing about the nature of the Titans, making them even more frightening: we fear what we do not know. However, the story gradually delves deeper into the horror of dark truths that become even more terrifying the more that is known about them.

Although the Titans are huge on a scale similar to Godzilla or King Kong, they also represent a type of horror commonly found in quieter stories on a smaller scale: the Titans appear similar to humans but for their size and animalistic expressions and tendencies. Having the appearance of a human places an uncomfortable feeling in the viewer and the characters; the monster is something close to being familiar and innocent and yet is corrupted in an uncanny way. This phenomenon can create such discomfort through its false sense of safety that even the most innocent people and objects, like children or dolls, become images of terror.

In an interview with Nihon TV, Isayama said that the inspiration for the Titans came to him after an unsettling encounter with a drunk customer at the Internet cafe where he worked. The customer, despite having the appearance of a fully functioning man, was unable to properly communicate due to his impaired state. Looking like a human yet behaving in a way that is uncommon lays the groundwork for a surreal experience – and, in this case, it also laid the groundwork for one of modern anime’s most dangerous monsters.

With the Titans, its own unique monster, the series could easily have stopped there and still have a good monster for the story. The Titans are easily identifiable, and they work thematically within the tale, their simplistic motivation serving as the perfect obstacle for the heroes. However, Attack on Titan’s themes cover far more than simple survival and fighting against a stronger opponent. This is not a simple David and Goliath type of story. For those who haven’t yet made it past Season 1 and would like to experience the story properly, be warned that there are spoilers ahead (and Attack on Titan is not a story that should be spoiled).

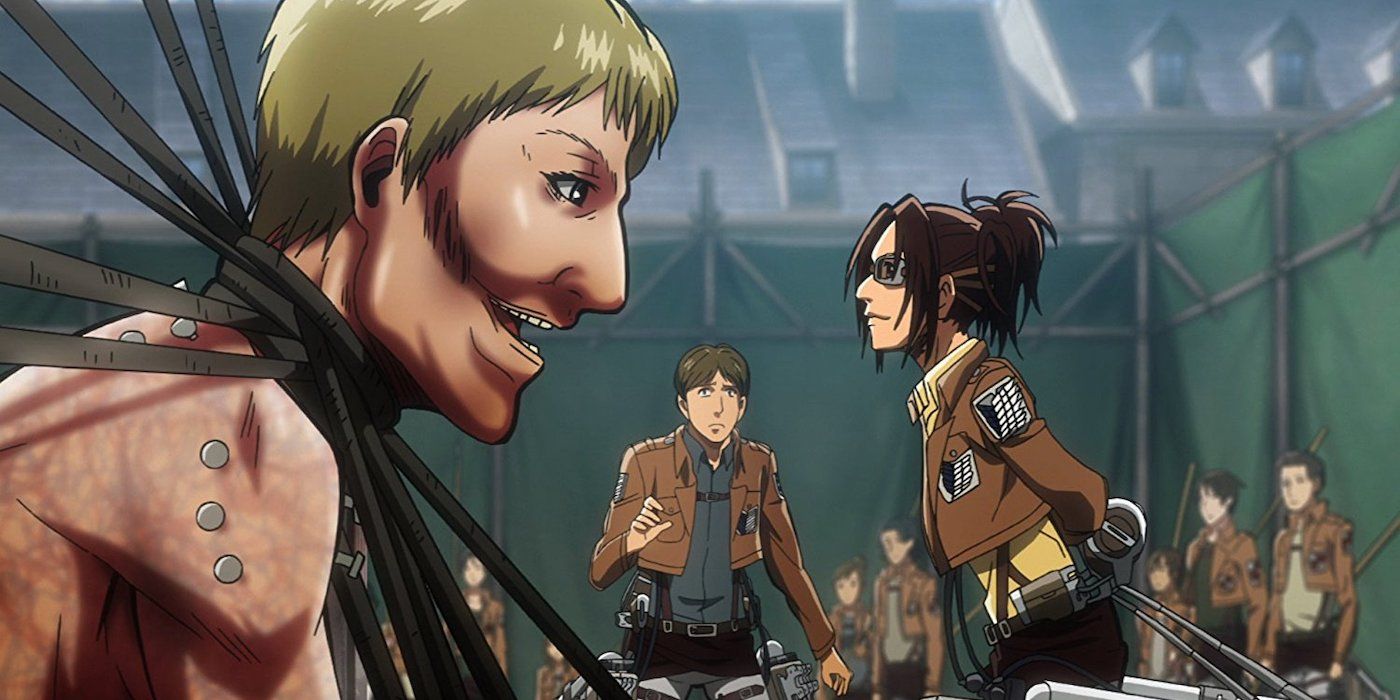

Isayama uses the idea of a “monster” to explore the darker side of humanity, especially following the revelation that contained within each Titan is a human person. Some of these Titan shifters use their monsters as weapons for war, even hiding among the heroes to await the perfect moment to strike. Now, the definition of a Titan (and of a “monster”) in the world of Attack on Titan has, itself, shifted. Instead of fighting against hordes of mindless monsters, the heroes now face actual humans who commit monstrous crimes; rather than humans versus monsters, the story has changed its dynamic to become heroic humans versus monstrous humans. Season 3 takes this moral situation a step further by introducing antagonists who are completely human, pitting humanity against itself and raising the question of what it means to be human at all.

During Season 4 (the massive final season not yet completed), this morally gray world becomes even more brutal. In the words of the in-universe strategist Armin Arlert (voiced by Marina Inoue): “To surpass monsters, you have to be willing to abandon your humanity.” This theme grows throughout the show, as the heroes, including the series protagonist Eren Jaeger (voiced by Yuki Kaji), fall down this slippery slope, first fighting what they assume to be mindless monsters, then evil traitors, then opposing humans – until they finally reach a point where the line between hero and villain is all but indistinguishable.

The newest evolution of Attack on Titan’s idea of monsters lies with the protagonist himself. While Eren’s plans to commit mass murder are shocking, this decision falls in line with the path that has been leading toward the ultimate monster, which is also the heart of its horror: an ordinary human’s capacity for evil. This parallels the misleading first impression that the Titans give, in that sometimes the most frightening and violent evil hides behind a familiar face. While the Titans look human, they are monsters; similarly, Eren has also become a monster.

It is not unheard of to take a protagonist down a dark path toward a tragic loss of humanity, therefore making them a villain. However, it is a difficult storytelling technique that, if done haphazardly or half-heartedly, can result in the protagonist’s turn feeling cheap. Attack on Titan navigates this change with grace; Eren’s turn is a gradual but seemingly inevitable one, especially considering that it has been foreshadowed since early Season 1.

His violent tendencies come to light when he saves Mikasa Ackerman (voiced by Yui Ishikawa) from kidnappers by stabbing two of them to death. This is a sympathetic situation, considering that both Eren and Mikasa are victims and children, but Eren’s actions and his inability to express regret create an unsettling juxtaposition with his appearance of an innocent child. When his father scolds him for acting rash and violent, and for putting himself in danger, Eren responds adamantly: “I killed some dangerous animals. They were beasts that just happened to look human.”

Living in a world of Titans, human-like monsters, has already begun to erode Eren’s morality when it comes to having sympathy for other human beings – even ones who have admittedly done despicable things. At this point, Eren has yet to understand that committing an evil act may be the actions of a monster but can also be the actions of a flawed human being. However, by the end of the story, Eren will understand that being human and being a monster are not mutually exclusive.

There are many other themes that Attack on Titan covers, from generational trauma to questions of free will versus predestination. However, the story’s subversion of the typical monster tale takes the fear of Godzilla, Jaws, and the like to a whole new level by slowly introducing the true monster of the story in a way that is foreshadowed from the very beginning.

As Isayama alluded to in that same interview with Nihon TV, the true horror, the true monster, of Attack on Titan, is the human being. Isayama demonstrates this truth of the story world by taking the protagonist, with whom the audience has sympathized and gone on an entire journey, and twisting him into a monstrous version of humanity, in the end leaving him sympathetic but still dangerous – not quite a tragic “hero,” and not quite a misunderstood “monster.” Just a human. Just like us. And this realization, that an ordinary human is capable of great evil while also keeping the connections, desires, and care for loved ones that exists at the heart of humanity, drives the horror home.

The use of the monster in this particular piece of fiction is, so far, threefold: the mindless killer, the deplorable but sympathetic human, and the hero with abandoned humanity. This subversive and layered approach to the depiction of monsters makes the horror story that much more terrifying – and human, in ways that present to the viewer a timeless but terrifying fear.