Editor's Note: The following contains spoilers for Avatar: The Way of Water.Any film that was as popular and acclaimed as Avatar was bound to attract a wave of backlash (especially after it took the crown of becoming the #1 highest-grossing film of all-time), but one of the stranger criticisms that the first film received was that it somehow left no cultural impact. This is clearly a misplaced critique, as the thematic subtext of Avatar actually resulted in a very serious discussion about James Cameron’s allegorical connections to American history. Many film fans have noted the similarities between Avatar and Dances With Wolves, as it's clear that the Na’vi are representative of indigenous peoples that were violently colonized. Both films have the same fundamental flaw; Jake Sully (Sam Worthington) and Lieutenant Dunbar (Kevin Costner) are essentially “white saviors” who come to lead native people against their conquerors.

While Avatar is done under a science fiction premise and doesn’t call specific attention to Sully’s ethnicity, it is clear that he is an outsider in the community who ultimately becomes their leader. It’s impressive that any film of Avatar’s scale would so blatantly tackle themes of anti-imperialism, but that doesn’t mean that it’s beyond criticism for how it connected to history. In the wake of Avatar’s continuing box office and awards success, there have been many thoughtful essays both praising and criticizing the film’s themes by skilled indigenous writers. Cameron himself has never been shy about admitting the comparisons; he stated that the film “is a science fiction retelling of the history of North and South America in the early colonial period,” and that “it’s not meant to be subtle.”

Avatar: The Way of Water benefits from a stronger screenplay than its predecessor which spends more time focusing on individual character arcs. Jake’s assimilation into the Na’vi culture is treated with more respect, as we see the struggles that he and Neytiri (Zoe Saldaña) face as they try to raise children who are decried as “outcasts.” The interactions between Jake and Neytiri's tribe of forest people and the reef people clan of Metkayina led by Tonowari (Cliff Curtis) and Ronal (Kate Winslet) provoke more nuanced cultural discussions. However, Cameron still shows the same obsession with showing colonialism in the most violent ways possible; his boldness is admirable, but it verges towards being exploitative.

A Not-So-Subtle Connection

As Cameron himself noted, part of the genius of Avatar is that the subtext is there in plain sight. It’s not a complex science fiction epic like Brazil or 2001: A Space Odyssey that requires multiple viewing to understand all of its metaphorical connections, as even someone watching Avatar on a surface level should be able to understand the glaring connections to American history. Unfortunately, there are so few films made starring indigenous people that reach a wide audience that these issues are rarely addressed in mainstream cinema; this saddles Cameron with greater responsibility, as he’s forcing a large portion of the audience to have a discussion that they would not have otherwise.

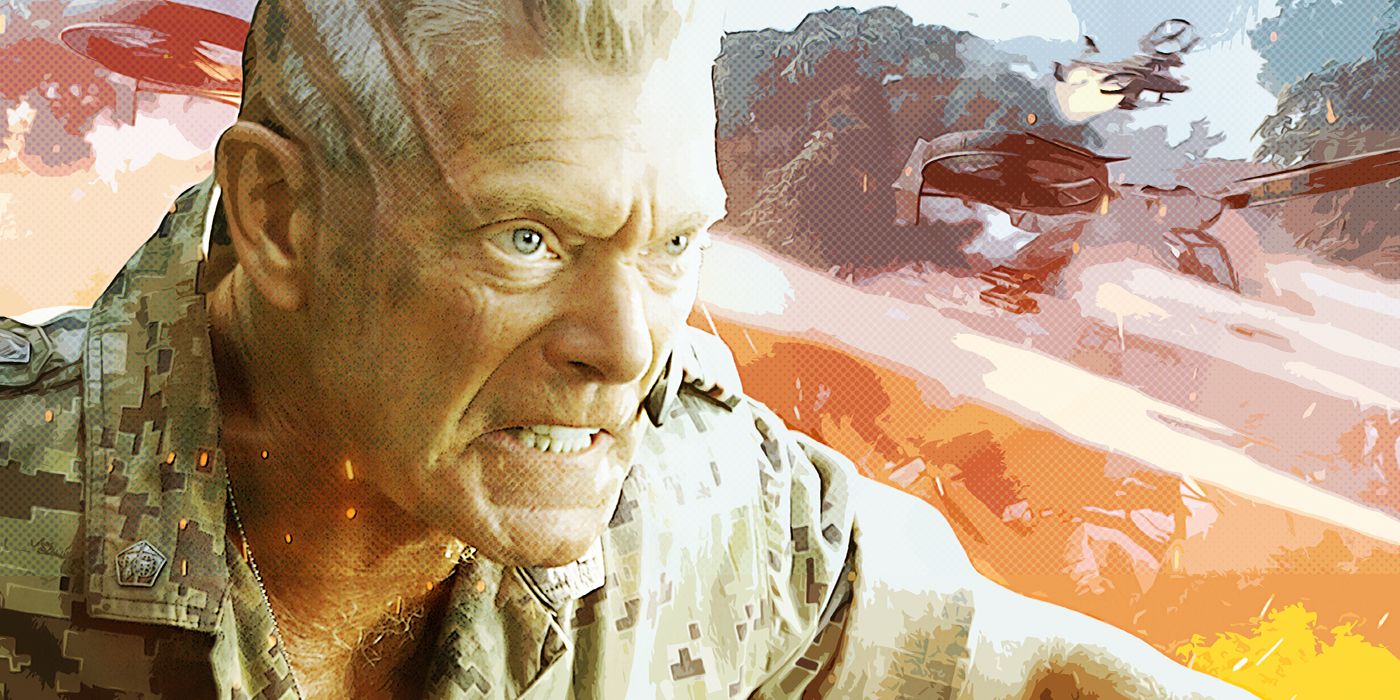

The first Avatar is relatively straightforward in showing the conquest of Colonel Quaritch (Stephen Lang), who is essentially the same sort of imperialist xenophobe that we see in many sci-fi action movies. However, The Way of Water spends more time showing the deep hatred that those in the RDA have for the Na’vi with more blatant xenophobic remarks. It’s clear that their decision to return to Pandora and strip it of its resources isn’t just out of greed, but out of cruelty. As General Frances Ardmore (Edie Falco) notes to a resurrected Quaritch before he begins his mission to draw out Sully, the only way that humans will be able to successfully migrate to Earth in order to take up residency is if the natives are completely “cleansed” from the surface.

The Extreme Side Of A PG-13

We see the beginning of this “cleanse” when the Omaticaya Clan falls under attack, and the Sully family is forced to depart their home in order to prevent more bloodshed. Their migration to a different land has striking parallels to the “Trail of Tears,” and it’s more than a little disturbing to see the separation of families and Neytiri’s heartbreaking sobs as she leaves the home that she has fought so hard to protect. The Way of Water addresses a complex dilemma that native people face: would you be willing to depart your home in order to protect it? Unfortunately, the Sully family’s exit doesn’t do anything to quell Quaritch’s conquest, as he proceeds to wreck environmental havoc on the Pandoran wildlife and overhaul their ecosystem.

This aspect of the film is just as unsubtle as the rest, so it’s particularly disturbing to see this sort of “total war” mindset within a film that’s otherwise trying to be a crowd-pleaser. Avatar may have gotten audiences to root against their own species, but The Way of Water shows in specific detail how evil the military-industrial complex is. Quaritch’s men set fire to the great barrier reefs, destroying their ecosystem for generations, and they execute Na’vi in cold blood and threaten their children. There’s a particularly unnerving moment when the brain enzymes of a tulkun are extracted by an RDA whaling vessel in order to use them for anti-aging remedies; after removing the critical brain fluids, Quaritch is willing to waste the rest of the creature’s body in an act of pure callousness, just so he can draw out Jake.

Emotional and Psychological Warfare

Watching Ronal sob over the slaying of these sacred creatures and the pain inflicted upon the Metkayina people as they also must contemplate potentially leaving their homes is where The Way of Water verges on exploitation; these characters have to be initially opposed to working with the Sully family for the sake of the plot, as it’s rather obvious that by the end of the story they’ll end up working together. Instead of showing Jake, Neytiri, Tonowari, and Ronal reaching an understanding after sharing their collective wisdom, Cameron insists on their alliance being a last-minute response to violence.

The Way of Water improves upon its predecessor in many ways, as the details of the Na’vi culture are fleshed out, the individual children are given interesting personalities, and the barrier reef people add an interesting new visual and cultural dynamic. The best parts of The Way of Water are those where we see the beauty of the Pandoran world, particularly during the children’s bonding with the sea creatures and their respect for the natural phenomena. It’s unquestionably one of the greatest visual achievements in cinema history, but it’s so often used to show in graphic detail some of the darkest periods in human history.