[Editor’s note: The following contains spoilers for The Banshees of Inisherin.]

‘Tis the season for awards attention, and one of the films in the running is The Banshees of Inisherin, from writer/director Martin McDonagh. Taking place on a remote island off the west coast of Ireland, the story follows Pádraic Súilleabháin (Colin Farrell), who unexpectedly finds himself reeling after lifelong friend Colm Doherty (Brendan Gleeson) calls it quits on their friendship. Not knowing how to deal with the decision, and refusing to take no for an answer, Pádraic continues to try to change Colm’s mind until everything escalates with shocking consequences that push both men to the brink.

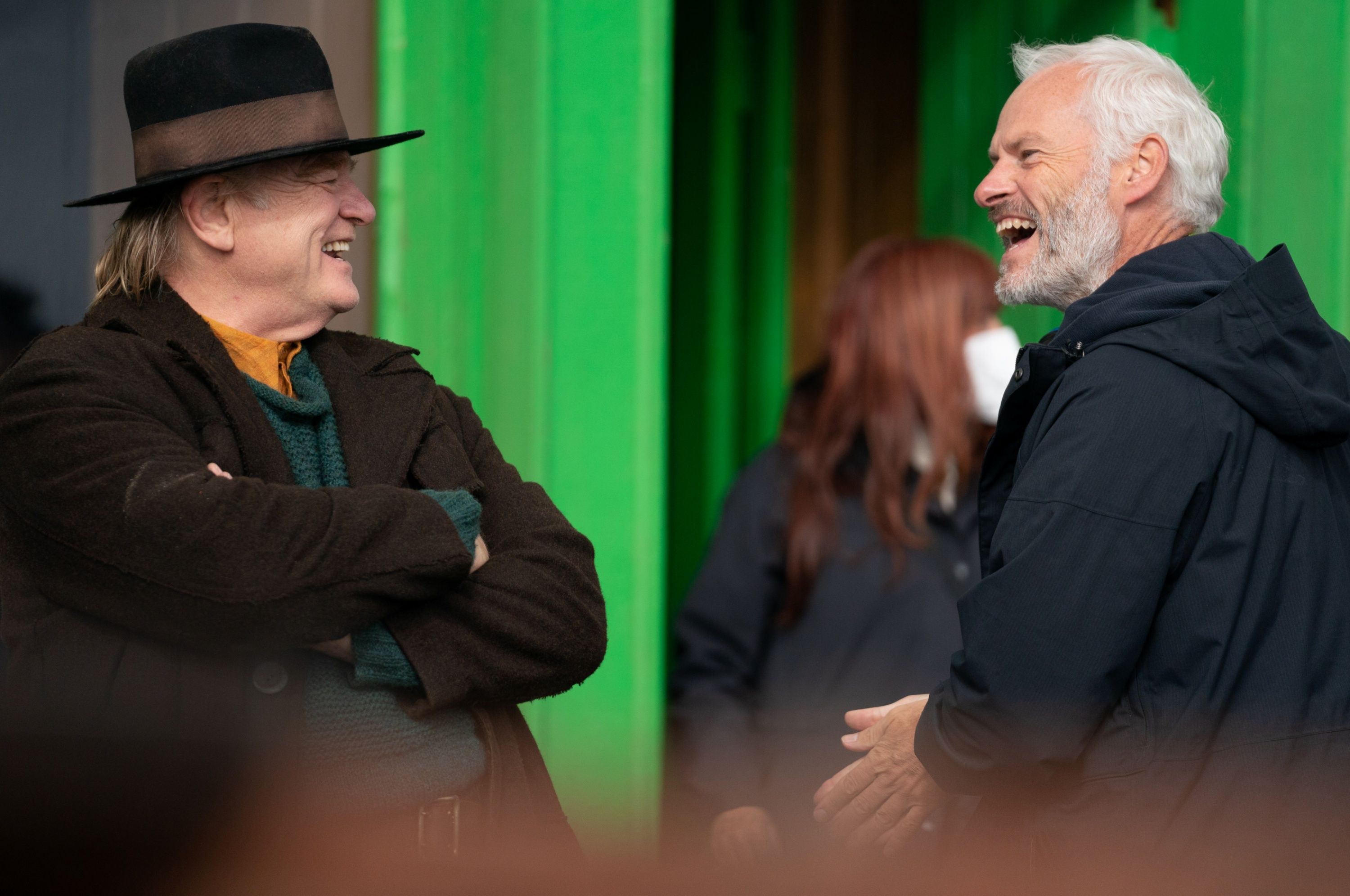

During a press conference for various critics groups, Farrell, Gleeson and McDonagh talked about these characters being written specifically for the actors who played them, the inspiration for this story, keeping friendships healthy in real life, the biggest challenges in getting this film made, eyebrow acting, what Farrell and Gleeson enjoy about each other’s work, how Jenny the donkey is the true unsung hero of the movie, and what legacy means to them.

Question: Martin, you wrote all four of the key acting roles for the people who ultimately played these characters. What was it about Colin Farrell, Brendan Gleeson, Kerry Condon and Barry Keoghan that spoke to you so passionately about wanting them to be in this story?

MARTIN McDONAGH: I love them all, as people. They’re just the best actors around. I think they’re very sensitive to sad, darker material, but also brilliant at understanding comedy, every single one of them. And they’re all mates, as well. I didn’t really know Barry beforehand, but Colin and Brendan and Kerry go back so far, from before In Bruges. Even before that, with Kerry, we did plays together 20 years ago. So, I knew they’d be brilliant, and I knew they’d bring everything to it, but I hoped we’d have fun making it too.

BRENDAN GLEESON: I think we did.

COLIN FARRELL: To a point.

Martin, for a movie about friendship, the fact that these folks have real friendships was meaningful and helped to augment the material?

McDONAGH: Yeah, I think so. The fact that Colin and Brendan love each other, and they’re playing the opposite of that, or they’re starting off in that place, from Colin’s perspective, and going to a darker, sadder place, it was great to have that founded on the care and love that they have for each other. That’s all palpable, from the very first minute of the film. You absolutely couldn’t have got that with two actors who didn’t have that affection and love for each other.

What was your inspiration for Banshees?

McDONAGH: It’s the simplicity of telling a story about a breakup, really, and to be as truthful and to show the pain of that. More than anything, that was it. To capture that juxtaposed with the Irish Civil War helped bring in interesting metaphorical angles to it, and show how a simple falling out can can lead to horror, to war, and to unforgivable acts. But the very initial impulse was to capture the sadness of a breakup.

Essentially, this is a love story. It’s a platonic love between men, and what makes it feel so wrenching is that it isn’t just a friendship. It really is a deep love that we see completely deteriorate in the confines of the story, which makes it so sad.

McDONAGH: Yeah. Sometimes it’s worse than a romantic breakup. You can work out or work through a romantic one, and you can understand why someone might not want to share a romantic love with you. But for a friendship, it’s much harder. It goes to the core of who you are. When they opt out, who are you, after that? How do you see yourself? That was some of the interesting things that we explored.

Brendan, Banshees has given you a chance to show a comedic side that we haven’t often seen from you. Was this an exciting challenge? Were you scared to delve into something a little bit more darkly comedic?

GLEESON: No. One of my first films was a film called I Went Down, which didn’t do a whole lot [in the U.S.], but it did really well at home, and that was pretty much out there. And a lot of my early stage work was with a group called The Passion Machine, and we did an awful lot of stuff in the eighties, where we were tearing around audiences.

It’s never been strange to me to go there. In fact, for a while, I was a little worried that I’d get overly typecast for being either a bouncer or a looper, or both. Early on in people’s careers, you don’t want to get branded because it’s very hard to come back from that, and it’s easier to go the other way. It’s just maybe over the last while, I haven’t had as much opportunity, but Martin’s stuff is always funny. In Bruges was hilarious. I think it speaks to the nature of Martin’s material that we always find it really hilariously funny, at the beginning, and then we go into rehearsal, and it turns out to be not quite so funny at all.

Colin, as someone who works and travels a lot, how do you keep your own friendships healthy?

FARRELL: That’s a great question. We’re a few months into talking about the film, and it’s not often that you hear a question that you have not heard before. I suppose technology helps with that, as much as it can. I don’t have any social media. I do, of course, have a cell phone, and I text and email. I’m not much of a talker on the phone, to the consternation of certain people in my life, at times. I can have the odd phone call, but usually I text friends that I have from home, who are people that have meant a lot to me, all my life. I have a couple of friends that I’ve known since I was born, literally from around the corner. The majority of my friends from home, from Dublin, are people that I’ve been pals with since I was 14 or so, and we’re all still in each other’s lives. They are friendships that don’t need to be constantly watered. They can go on with their lives and do their things, and I go and do my things, and we may not see each other. There have been periods where we haven’t seen each other for 18 months, but as soon as we see each other, we pick up where we left off.

There’s a depth of friendship that I’m lucky enough to have in my life with a few people that hasn’t fallen off, regardless of the distances I’ve traveled. My big concern is that you have friends and family, but you just have to check in. Those who are really close to me in my life understand, to a certain degree, the nature of the travel and the distance. I get lost when I go off to work and might not be in communication for the first month as much. But then, once I get up and running on a job, and I feel a little bit of comfort in the job or there’s a rhythm, then I may open up to communication again, a bit. But there’s no set rule. The people that mean a lot to me know that they mean more to me than any of the films, or any of the work that I can ever do. At least, I think they do. If I do go missing for a while for work, they know it’s not that I’m putting one in front of the other, I’m just focused on one at a time.

Martin, what were your biggest obstacles in getting this film made? What presented the largest challenge for you?

McDONAGH: COVID delayed us for probably about a year, in all.

FARRELL It probably did us a favor with the weather we ended up getting. It would have been bleak. It was so lovely that the weather was gorgeous while this horrible carcinogenic thing was taking over.

McDONAGH: That summer was idyllic. I’ve never had one like that. Whatever problems you have, in trying to get something on, it usually helps somehow. Everything happens for a reason, whether it’s recasting, or whatever kind of delay. It also gave me, the production designer, Mark Tildesley, the DP, Ben Davis, and the first ADP, Peter Kohn, a year beforehand to just go through the entire schedule, to work out when we wanted to be inside, when we wanted to be outside, when it didn’t matter, what scenes we wanted rain for, what scenes we would really go out for sunshine, etc. Extra time is always good, and because of COVID, we had that.

In terms of financing, it was all great. Searchlight and Film 4 came in really early. I’d worked with them both before. I know people usually like hearing tales of woe about getting a film, but everything worked out perfectly, and we had a great time. I think everyone should work that way.

Why did you pick a fictional setting for the story of Inisherin, and what creative freedoms come with setting a story in a world that doesn’t actually exist?

McDONAGH: Good question. The original title of this was The Banshees of Inisheer, which is the third of the Aran Islands and the smallest of them. I looked around there, just on my own, about two or three years ago, and it’s a beautiful island, but it wouldn’t have given us the scope of the landscape, and there was too much modernity to the place. So, I wanted to keep a semblance of that name, so that we could amalgamate the island that we filmed on, which was Inishmore, the largest of the Aran Islands, and Achill Island, which I hadn’t really explored or been to before. I’d seen a photo of a house on a beach there, which turned out to be the house that became Brendan’s house. And then, the mountainous side of Achill, we amalgamated with Inishmore. It gave us the choice of two locations, but it also meant, in terms of the accuracy of what was happening in the Civil War on the mainland, that we didn’t have to be as specific. Also, in terms of accent, it didn’t have to be a terribly very specific islands accent. It just freed us up, in so many ways. I’m so glad we made that choice.

Colin and Brendan, what are your favorite performances of each other’s work in other films, and why?

FARRELL: I haven’t seeing anything else that Brendan’s done. I’ve heard he’s very good.

GLEESON: I’ve been waiting for the screeners to come in to see a few of his films.

FARRELL: He has this new one coming out, called Braveheart, that I can’t wait to see. No. I have to say, his character in Braveheart is just indelible. It’s one of those that stays with you. And the work he did as Winston Churchill, I have to say, was astonishing, really. It was just the boldness of a man, such as himself, with his love and his affection around Irish history, there was a brilliance and commitment and passion and intelligence of the interpretation. He was extraordinary in that, and in everything he’s done. I didn’t tell him, but I watched Mr. Mercedes, and my God, it was brilliant. I’ve always said about him, he hasn’t got a dishonest bone in his body. I can be a bit shifty, in that way. There’s no dishonesty in him, as a man, and there’s no dishonesty in him, as an artist. Every time he goes to work, it’s just an extraordinary experience to watch what he’s doing.

GLEESON: I’ll echo that. I wanted Colin to do something in a film that I was trying to make. That’s why we first met, at the Chelsea Hotel, a year or two before. Domhnall [Gleeson] put me in the hotel because he was doing Martin’s play, The Lieutenant, on Broadway, and I went over to see him. I was hoping to get a film made, so I met Colin because I was hoping maybe he’d be interested. Going back to all the stuff that he’s done, watching somebody emerge, his trajectory was so explosive, and then watching the artist emerge in all its different forms, it was almost a bit like the Harry Potter years, where you watch these kids grow up within films.

His craftsmanship has always been there, and his honesty has always been there, and his accessibility to the emotional side of things, but I’ve been watching him strip away, more and more. His heart has always been there, but in the last couple of years, the choices that he’s been making, particularly since In Bruges, have been exploratory and incredibly brave. It’s an artistic journey that he’s on. And being across from him this movie, our job was to make each other’s lines as difficult as possible to say. I was looking at somebody whose heart is visibly breaking and trying to tell him there’s no place in my life for him anymore. There was a degree of honesty that we shared across that because there had been history. You don’t actually see, at all, us as friends, prior. So, it had to come from what was communicated when the sundering was happening. I can still remember every frame, every altercation, and how difficult it was to get these lines out. I think Colin’s artistic journey is spectacular. Trying to pick one film out is weird because it feels there’s a progression, all the time, in terms of just the way life progresses. The performances are all different. They’re all immensely different. He explores different areas of both himself and the material, and it’s just a pure pleasure to watch him.

Colin, can you talk about how you use your eyebrows as an expressive acting tool?

FARRELL: No, I have no idea. They just do their own thing. They’re like the Energizer bunnies, at times. They operate exclusive of my intention, I can tell you that for sure. They do their own thing. Apparently, the more I’m perturbed, the more active they are.

Martin, how long was the writing process for Banshees?

McDONAGH: It’s a tiny bit complicated. There was a version of this probably seven or eight years ago, which was a load of shit.

FARRELL: It was actually really good.

McDONAGH: It was just not good enough. I put it completely out of my mind, until about three and a half years ago now. I reread it, and the first five pages were quite good. The first five pages are literally the exact same as the first five minutes of this film, going to Brendan’s house and the breakup. Everything else after that is a new story without plot. The first film had, for me, just way too much plot with outside characters coming in. This was more about mining the details in those first five pages and mining a breakup. So, when I put pen to paper, there was something so freeing about that idea of getting rid of plots and trying to be truthful to the pain of a breakup, and it wrote itself in three or four weeks, to be honest.

But that also doesn’t take into account all the thinking that has taken place before the writing, right?

McDONAGH: I don’t do that, actually. I try not to do any thinking. It seems like a waste of time, especially if the World Cup is [on]. I think on the page. Of course, you’ve got a background of who you think each of these characters are, so that’s there. But when it goes at its best, you’re literally copying down what people are actually saying because the characters are there. Especially when you’re writing for Colin and Brendan, you can hear their voices and their sensitivities and their sadness and their humor. But when it goes well, you’re literally just trying to keep up with how quickly they’re talking.

Colin and Brendan, what have you learned about acting from each other?

GLEESON: There’s a joy that I feel, working with Colin, and what it does for me is that it reaffirms. It’s been the same, working on Martin’s material, and working with everybody in this cast, really. It reaffirms that there’s a certain way to approach this work, which is collaborative and honest and fearless, and only about raising the bar. Colin has a luminosity that stars have. There’s nothing I can learn from looking at it, other than to see and love it, and say, “That’s a beautiful thing.” In terms of the acting, we understand that there’s an intellectual part of the work that’s crucial to it, and then there’s an instinctive part, and then there’s a craftsmanship that you need to know. All of these things have always been collaborative with Colin, and that just reaffirms what I’ve known for a long, long time now, which is that it’s the only real way to work. It’s not the only way to work for everybody, but all of us like to work that way.

FARRELL: It’s the nature of collaboration, and not just the theoretical offering, but it’s a good and healthy, constructive thing to be concerned about your scene partner and the people that you’re working with. Loving words only work for so long. There has to be action in there. So, to actually inhabit that and to live in a concern for your scene partners and your fellow actors, and to know that their concerns are your concerns, and your concerns are their concerns, whether they’re spoken about or not. You don’t live in a vacuum, as a storyteller, doing what we do. You live by the breadth and the actions of the people that are sitting across from you. It’s what Peter Weir had talked about. It’s not about the actor’s ego. It’s about the script’s ego. It’s about the film’s ego. The script and the film have the ego, and our job is to take care of that and to serve the ego.

Martin is the one who brings the story into being and is the genesis of everything that we’ve done together. Brendan and I, and Kerry and Barry, are the tools, and we all really believe that, in terms of the story, we’re not serving our own proclivities, our own desires, our own ambitions. Our proclivities and our desires and our ambitions get to come to the party. They’re invited, for sure, but we’re serving the story, and we’re serving each other. It’s the meeting point of these psychologies that we all share, in regard to the creative process, that makes it such a joy. We had three weeks rehearsal on both projects, and it was about getting enough familiarity to then go onto the set and feel like you had the freedom to continue to explore. When you have that trust in your fellow performer and actor, and your director, you can go anywhere. You’re not afraid to fail. And if you’re not afraid to fail, you’re in good shape. If you’re afraid to fail, as actor, and I have felt that before, then you’re limited to what you can do.

Jenny, the donkey, truly is the unsung hero of this story. Colin, how much time did you have to spend with Jenny, in order to establish the bond that you ended up having on screen?

FARRELL: The bond that we ended up having on screen might be a result of editorial smoke and mirrors, shall we say. No. I was well fond of her. She was very sweet, but I’m sure she was confused. Film sets can be a very overwhelming place, if you don’t know what you’re doing there, and you haven’t got a purpose there. I’m not sure that Jenny knew we were on a film set, as much as I told her. And she had a support donkey, called Rosie, because Jenny would get a bit nervous sometimes. They’d bring Rosie in, and Jenny would see Rosie, and then she’d be all right, and she’d do the scene.

She was as cute as a button. The best thing about the donkey, and any of the animals on the film, and it can be the same with kids, is that when there’s not too much stage parenting involved, there’s honesty there. You’re at the whims of the honesty of this thing, particularly with animals. The human child lies better, of course, than an animal does, but not as well as grownups, but the animals are totally honest. So, when Jenny was on the set, in the middle of a scene, she’d get up and go, and that would be the end of it. And then, the trainer would come in and spend 20 minutes. Everyone was incredibly patient. There was no pressure. There was no, “Come on, you better get to it.” It was her first film, and I think it might have been her last. It was one and done for her. She’s out in a pasture now.

Over the years, I’ve worked with horses and dogs. It was the first time I’d worked with a donkey, but she was great. She’s such a very real and very present part of the film and the landscape, but also Pádraic’s emotional world. She was a rescue donkey, rescuing him from his own boredom. She’s the final straw. He loses the sister, the friend, and any standing in the community, but the final straw was Jenny. It’s so crushing for him. She represents innocence, in a similar way that Barry’s character, Dominic, does. I don’t represent innocence. I’m more than a willing participant in my own downfall. I can understand and justify the reasons why I push back, and why I won’t accept his ultimatum or his dictum, and I won’t leave him alone. I understand the pain that compelled me to continue to try to reach out, but I’m a participant in my own downfall. But Barry’s character Dominic, and very much Jenny, are two innocents that really suffer, as a result of this contained Civil War between me and [Brendan].

Colin and Brendan, what are the priorities in your life, in terms of legacy, that are important to you?

FARRELL: You just wanna do good stuff. Sometimes you’re going to work for entertainment and the money might be a bit better. Sometimes you’re going to work to satisfy your own curiosity. Whatever the reason, you have an understanding. Whatever the gig is, if it’s made for purely entertainment purposes, or for some greater intellectual or social provocation, you just wanna make something where people don’t waste an hour and a half, or two hours, of their lives, as simple as that sounds. If you do that, and if you live as authentically as you can in your life and in your art, then the legacy thing will take care of itself. Your legacy is through the friendships, and the people that you’ve met, and you’ve touched, and all that. Don’t get me wrong, when I saw that The New World was being put into the Criterion Collection, I did get tickled. One of my kids said to me, a while back, when he was talking about fame, “It’s weird, dad, in a hundred years, nobody will remember anything you’ve done.” I was like, “Maybe a hundred and fifty.” You can’t be concerned with that.

GLEESON: Living in the moment is its own legacy and its own priority. I do feel that good art, for me, is generous. You’re attempting, in a way, to make sense of the world, or to record beauty, or to express a form of beauty. It’s the exploration of things that other people mightn’t have seen, and you’re putting it in front of their eyes. For me, in regard to acting, it’s not therapeutic for me, it’s therapeutic for the audience. That’s the duty. Legacy is built from a conscience, where he feels the need to give back. To feel useful, to feel creative, to not have wasted your time on earth, to have this one chance at life and not to give something of yourself that will last, it’s generous in nature. It’s about sharing some beauty that he’s managed to channel and sculpt out of a rock, and put a tune out in the world that wasn’t there before. I don’t think it justifies any cruelty toward those in your general area. I don’t think it gives people that license. Sometimes there is a bit of difficulty, if there sometimes has to be a bit of collateral damage, but something magnificent can be achieved. A lot of the great artists have had to face that. Even us, when we’re involved in our work, we can be moody, in terms of the peripheral damage we cause around us. It’s a question of how much you limit it.

FARRELL: I’m glad you own it, at last.

The Banshees of Inisherin is now available to stream on HBO Max and to purchase on digital.